Sex and Gender Minority

Health and Social Inequities of Sex and Gender Minority (SGM) Patients and Providers

Author(s): Michelle D. Lall, MD, MHS and Lachlan Driver, MD

Editor: Tania Strout, PhD, RN, MS

Definition(s) of Terms

Starting with a common understanding of key words, phrases, and potentially misunderstood related terms in DEI discussions helps ensure that all participants feel informed and welcome to participate in the discussion. Some terms have multiple definitions provided to help highlight nuances in the definitions.

Sex and Gender Minority #1: Sexual and gender minority (SGM) populations include, but are not limited to, individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, asexual, transgender, Two-Spirit, queer, and/or intersex. Individuals with same-sex or -gender attractions or behaviors and those with a difference in sex development are also included. These populations also encompass those who do not self-identify with one of these terms but whose sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, or reproductive development is characterized by non-binary constructs of sexual orientation, gender, and/or sex. https://dpcpsi.nih.gov/sgmro (1)

Sex and Gender Minority #2: Sexual Minority: Individuals who identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual, or who are attracted to or have sexual contatct with people of the same gender.

Gender Minority: Individuals whose gender identity (man, women, other) or expression (masculine, feminine, other) is different from their sex (male, female) assigned at birth. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/terminology/sexual-and-gender-identity-terms.htm (2)

Sex and Gender Minority #3: LGBTQIA+, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer/Questioning, Intersex, Asexual (or their Allies)/Aromantic, + (inclusive of other identities not listed)

Synonyms/Related Terms

This section highlights definitions of other words that may be used in discussion of this topic. Sometimes these words can be used interchangeably with the terms defined above, and sometimes they may have been used interchangeably historically, but have distinct meanings in DEI conversations that is helpful to recognize.

Bisexual: A person who is attracted to both people of their own gender and other genders.

Gay: A person who is attracted primarily to members of the same gender. Gay is most frequently used to describe men who are attracted primarily to other men, although it can be used for anyone who does not self-identify as ‘straight’ (see below).

Straight/heterosexual: A person who is attracted primarily to members of the opposite gender, typically men who are attracted to women, and women who are attracted to men.

Gender: The cultural roles, behaviors, activities, and attributes expected of people based on their sex.

Gender Expression: How an individual chooses to present their gender to others through physical appearance and behaviors, such as style of hair or dress, voice, or movement.

Gender Identity: An individual’s sense of their self as man, woman, transgender, or something else.

Cisgender: Individuals whose current gender identity is the same as the sex they were assigned at birth.

Transgender: Individuals whose current gender identity differs from the sex they were assigned at birth.

Gender Nonbinary: Individuals who do not identify their gender as man or woman. Other terms to describe this identity include genderqueer, agender, bigender, gender creative, etc.

Gender Nonconforming: The state of one’s physical appearance or behaviors not aligning with societal expectations of their gender (a feminine boy, a masculine girl, etc.).

Lesbian: A woman who is primarily attracted to other women.

Two-Spirit: A Two-Spirit person is a male-bodied or female-bodied person with a masculine or feminine essence. Two-Spirits can cross social gender roles, gender expression, and sexual orientation.

LGBTQIA+: Acronym that refers to the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, intersex, and asexual/aromantic community.

Queer: An umbrella term sometimes used to refer to the entire LGBTQIA+ community.

Questioning: For some, the process of exploring and discovering one’s own sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression.

Sex: An individual’s biological status as male, female, or something else. Sex is assigned at birth and associated with physical attributes, such as anatomy and chromosomes.

Sexual Orientation: Refers to a person’s sexual attraction to another person and the behavior and/or social affiliation that may result from this attraction (lesbian, gay, bisexual, asexual, etc.)

Romantic Orientation: Refers to a person’s romantic or emotional attraction to another person and the behavior and/or social affiliation that may result from this attraction (homoromantic, biromantic, aromantic, etc.)

Misgendering: Refers to using a word, especially a pronoun or form of address, that does not correctly reflect the gender with which they identify.

Dead name: The birth name of a transgender person when they have changed their name as part of their gender transition.

SGM: Acronym for sexual and gender minorities.

SGMY: Acronym for sexual and gender minority youth.

SMY: Acronym for sexual minority youth.

https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/terminology/sexual-and-gender-identity-terms.htm (2)

https://www.apa.org/pi/lgbt/resources/sexuality-definitions.pdf (3)

https://www.ihs.gov/sites/telebehavioral/themes/responsive2017/display_objects/documents/slides/lgbt/lgbtnativeout.pdf (4)Scaling This Resource: Recommended Use

As many users may have varying amounts of time to present this material, the authors have recommended which resources they would use with different timeframes for the presentation.

For a 1 minute presentation, the authors recommend focusing on “The Gender Unicorn” in Slide Presentation or Images section.

For a 10 minute presentation, the authors recommend presenting the definition of terms, vernacular and “The Gender Unicorn” in Slide Presentation or Images section.

For a 30 minute presentation, the authors recommend adding the importance of allyship, statistics of note, TG/GNB stories, and 1-2 role play scenarios in addition to the content in the 10 minute presentation.

Sex and gender minority is a complex topic with many components. The dearth of physician education in this subject matter has been well documented. The authors recommend a presentation of background information followed by a facilitated discussion of the recommended literature in addition to 1-2 role play scenarios.

Discussion/Background

This section provides an overview so that an educator who is not deeply familiar with it can understand the basic concepts in enough detail to introduce and facilitate a discussion on the topic. This introduction covers the importance of this topic as well as relevant historical background.

The abbreviation LGB (for lesbian, gay, and bisexual) gained popularity in the 1980s. In the 1990s, LGBT (with T for transgender) became more widespread. Since then, additional letters have been added to be more inclusive of those who identify in ways different than those already represented. LGBTQIA+ and similar abbreviations are intended as umbrella terms in an attempt to encompass a number of different communities under one label. https://www.dictionary.com/browse/lgbtqia (5)

In a 2020 Gallup Poll, 5.6% of Americans identify as LGBTQIA+. This estimate has risen more than one percentage point from 2017. The majority of LGBTQIA+ Americans say they are bisexual, and one in six adults in Generation Z consider themselves LGBTQIA+. https://news.gallup.com/poll/329708/lgbt-identification-rises-latest-estimate.aspx (6)

To provide competent care to patients that identify as a sex or gender minority, it is important to understand the interplay of gender, sexual orientation and societal/cultural norms and their impact on patients’ health. Competence regarding sex and gender minorities and the microaggressions, macroaggressions, and barriers they face in the workplace is also critical in creating an inclusive and safe workplace for physicians (including medical students and trainees) identifying as a sex or gender minority.

Concerns for SGM Healthcare Providers

Studies have shown that people who self-identify as sex and gender minorities (LGBTQIA+) experience harassment and discrimination in the workplace (7,8). Mistreatment among LGBTQIA+ resident physicians is prevalent (9,10) and emergency medicine is no exception with 56.2% reporting discrimination from patients/patient families and 13.8% reporting discrimination from co-residents (11). Patients are also a frequent source of mistreatment for physicians identifying as SGMs (10,11). Many institutions do not have a patient code of conduct that is inclusive of mistreatment of SGM employees (12). Perhaps unsurprisingly, mistreatment in the workplace results in increased emotional distress and burnout (11,12).

Other barriers faced by physicians who are transgender and/or non-binary (TGNB) may include being obligated to use their dead name (the birth name of a transgender person who changed their name as part of their transition) for credentialing and licensing purposes, lack of mentorship by more senior physicians identifying as SGMs, inappropriate interview questions, and outright hostility (13). Additionally, prior studies of SGM physicians have demonstrated high rates of discrimination, harassment, social rejection, and witnessing discrimination against patients and colleagues. This includes a majority of participants hearing colleagues disparage LGBTQIA+ patients and a significant minority (over 30%) witnessing discriminatory care, suboptimal care, or even refusal of care for LGBTQIA+ patients (13,14). In a study of transgender and/or non-binary medical students and physicians, 22% witnessed discrimnatory treatment of a TGNB peer, colleague, or superior, and 78% censored speech and/or mannerisms at least of the time while at work/school to avoid unintentional disclosure of their TGNB status (13). Below are several pertinent quotes from this study that highlight the current climate in healthcare for physicians and trainees:

- “I faced overt verbal abuse and discrimination by nurses, med techs, residents, and attendings with no recourse, no protections or support by the med school, and no mentors or advocates.”

- “On rotations I have experienced everything from listening to other staff/residents joking about how ‘freakish’ a trans patient is to experiencing a transgender patient being assaulted by a resident. I do not feel safe being out in my 3rd/4th year rotations at all.”

- “[I witnessed] derogatory jokes about trans patients, misgendering, misnaming, speculating about their sex/gender, [and] judging patients' gender identity and ‘successfulness' of their transition based on how they visually looked.”

Creating an inclusive and safe environment is critical in supporting the advancement of TGNB colleagues, trainees, and medical students, which in turn could lead to improved health care and health outcomes of patients who also identify as such.

Importance of Allyship

For the LGBTQIA+ community, an ally is a straight and/or cisgender person who supports and advocates for LGBTQIA+ people. Often, allies come together at Pride events, for instance, to uplift and strengthen the community—particularly Black and brown LGBTQIA+ people who face greater threats of violence.

6 Ways to Be an LGBTQIA+ Ally and Supporter

https://www.oprahdaily.com/life/relationships-love/a28159555/how-to-be-lgbtq-ally/#:~:text=For%20the%20LGBTQ%20community%2C%20an,face%20greater%20threats%20of%20violence (15)

10 Ways to Be an Ally and Friend

https://www.glaad.org/resources/ally/2 (16)

Quantitative Analysis/Statistics of note

This section highlights the objective data available for this topic, which can be helpful to include to balance qualitative or persuasive analysis or to help define a starting point for discussion.

References are with each individual slide (17-21)

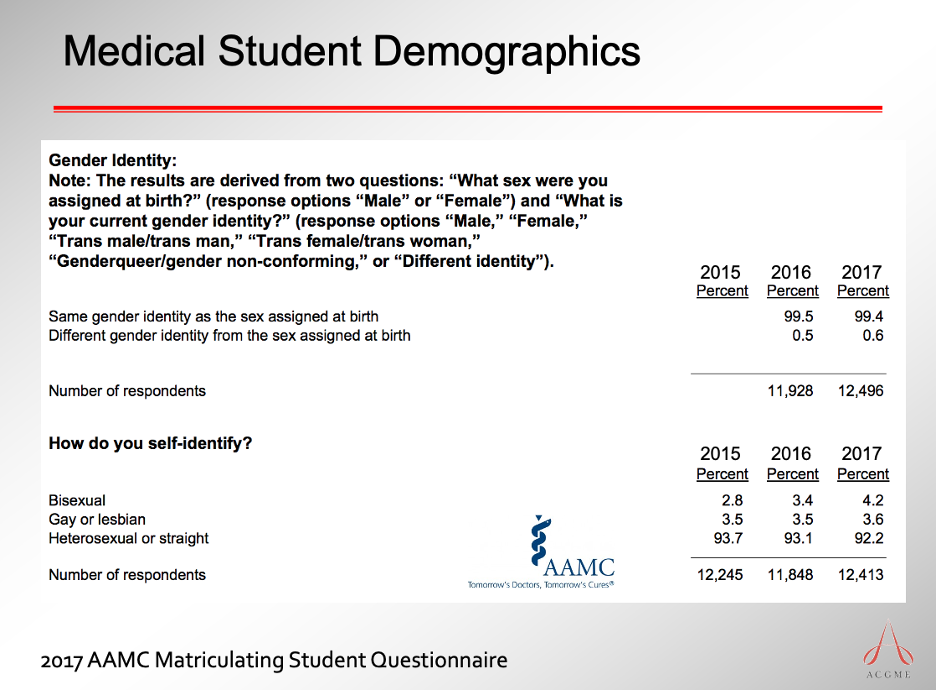

(17)

(17)

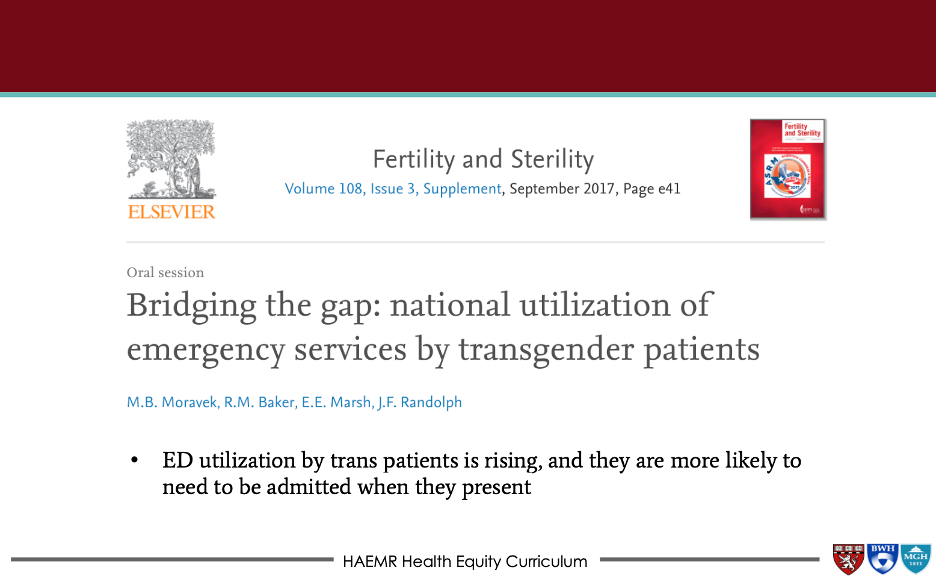

Moravek MB, Baker RM, Marsh EE, Randolph JF. Bridging the gap: national utilization of emergency services by transgender patients. Fertility and Sterility, 2017, Volume 108, Issue 3, Pages e41-e41. (18)

Moravek MB, Baker RM, Marsh EE, Randolph JF. Bridging the gap: national utilization of emergency services by transgender patients. Fertility and Sterility, 2017, Volume 108, Issue 3, Pages e41-e41. (18)

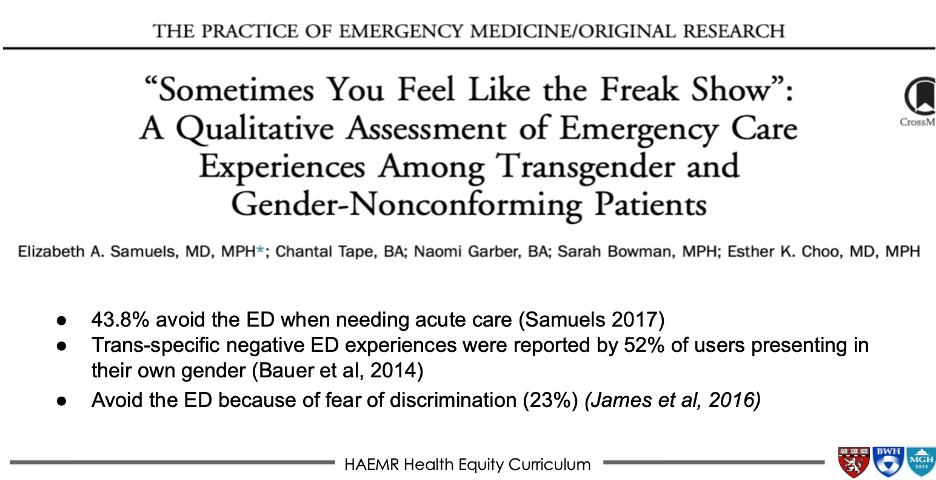

Samuels EA, Tape C, Garber N, Bowman S, Choo EK. “Sometimes you feel like the freak show”: a qualitative assessment of emergency care experiences among transgender and gender-nonconforming patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2018; 71(2):170-182. (19)

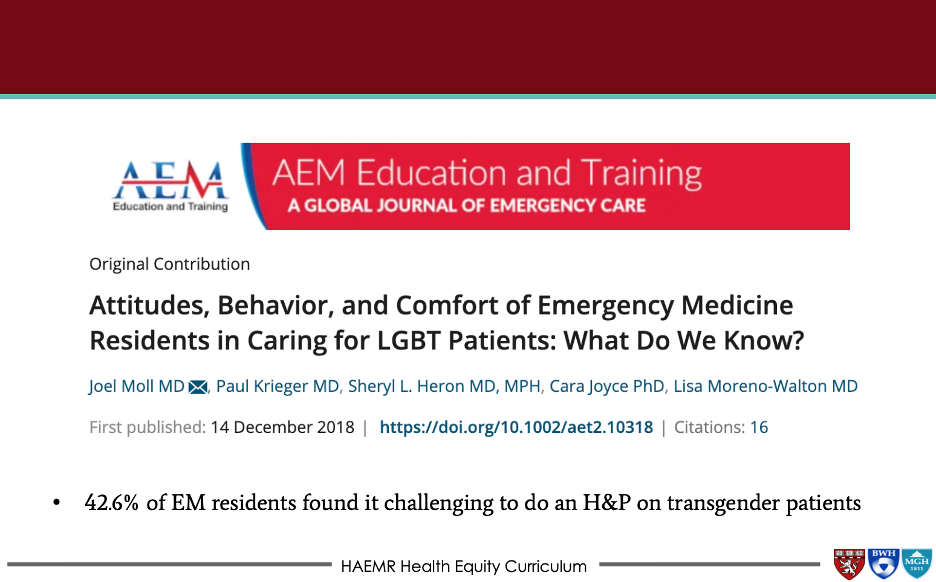

Moll J, Krieger P, Heron SL, Joyce C, Moreno-Walton L. Attitudes, Behavior, and Comfort of Emergency Medicine Residents in Caring for LGBT Patients: What Do We Know? AEM Educ Train 2019;3(2):129-135. (20)

Moll J, Krieger P, Heron SL, Joyce C, Moreno-Walton L. Attitudes, Behavior, and Comfort of Emergency Medicine Residents in Caring for LGBT Patients: What Do We Know? AEM Educ Train 2019;3(2):129-135. (20)

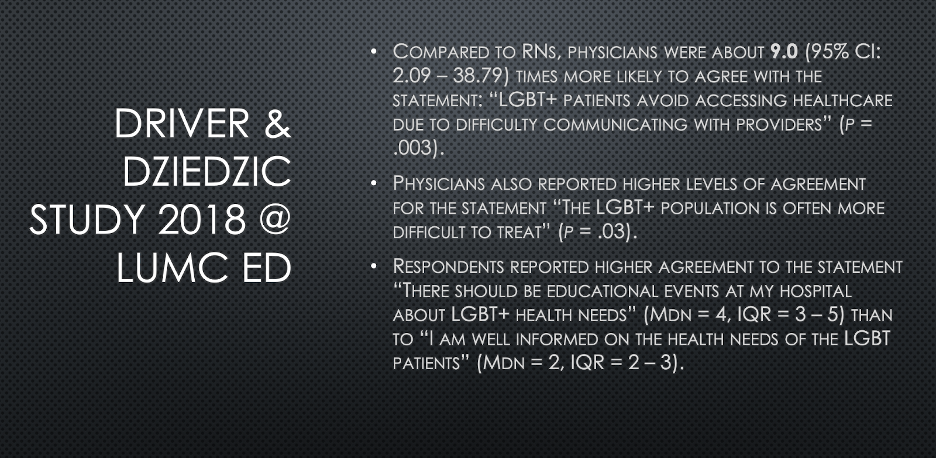

Driver L, Adams W, PhD, Dziedzic JM. Attitudes, Behavior, and Knowledge of Emergency Medicine Healthcare Providers Regarding LGBT+ Patient Care, Loyola Medical Center, Emergency Department, WestJEM abstract published, June 2019. https://tinyurl.com/nd82n8y7. (21)

Slide presentation or Images

Images and graphical representations in presentations can clarify concepts and enhance interest. Please cite the sources of these images appropriately if you use them in your presentation, found in the last section of this page. We purposefully avoided providing complete slide decks in this curriculum, and instead opted to offer easy building blocks for a great personalized presentation regardless of the format. Trans Student Educational Resources, 2015. “The Gender Unicorn.” http://www.transstudent.org/gender. (22)

Trans Student Educational Resources, 2015. “The Gender Unicorn.” http://www.transstudent.org/gender. (22)

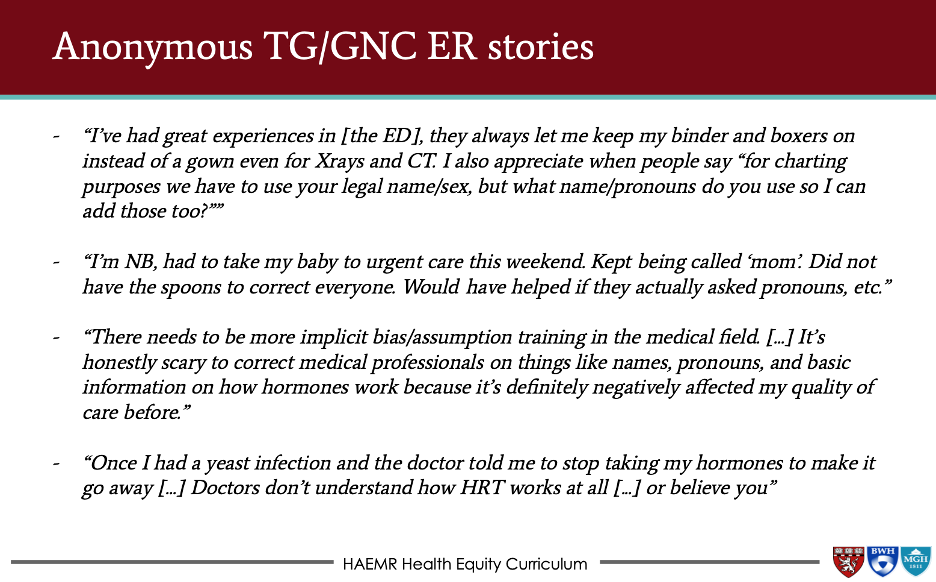

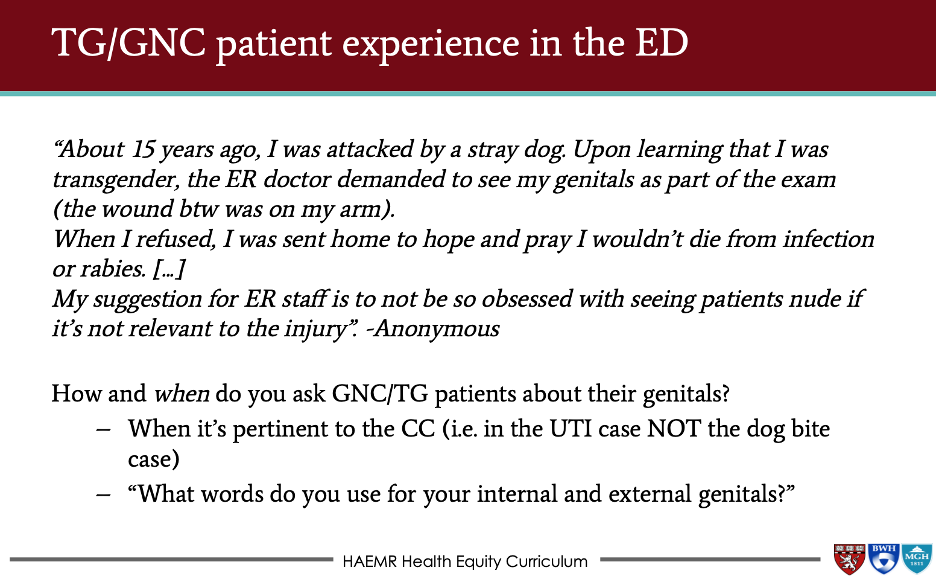

Treating Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Patients in the Emergency Department, Lachlan Driver, MD, HAEMR M&M lecture, November 9, 2021, MGB, Boston, MA (23)

Treating Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Patients in the Emergency Department, Lachlan Driver, MD, HAEMR M&M lecture, November 9, 2021, MGB, Boston, MA (23)

Treating Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Patients in the Emergency Department, Lachlan Driver, MD, HAEMR M&M lecture, November 9, 2021, MGB, Boston, MA (23)

Treating Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Patients in the Emergency Department, Lachlan Driver, MD, HAEMR M&M lecture, November 9, 2021, MGB, Boston, MA (23)

Role-playing Scenario

Role-playing scenarios can enhance investment and participation. Always consider psychological safety when asking participants to engage in any role-playing activity to avoid potential adverse effects. We highly recommend a discussion for each group to agree on ground rules of respectful learning prior to engaging in any role-playing scenarios (embrace ambiguity, commit to learning together, listen actively, create a brave space, suspend judgment, etc.). It is reasonable to review these ground rules prior to each role-playing discussion.

Learning to address implicit bias towards LGBTQIA+ patients: case scenarios https://www.lgbtqiahealtheducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Implicit-Bias-Guide-2018_Final.pdf (24)

Additional real-life cases with questions: (all from Treating Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Patients in the Emergency Department, Lachlan Driver, MD, HAEMR M&M lecture, November 9, 2021, MGB, Boston, MA) (23)

Case #1

‘Sam’ is a transfeminine NB (AMAB) patient here for a ‘hand injury’. The well-meaning resident calls a consult. While sharing the history, the resident says, “This is a 30yo male patient, he goes by ‘Sam’, prefers ‘they/them’ pronouns, he injured himself when he…” The consultant: “Wait, is this a man?” The EM resident: “I think it’s a male-to-female trans patient....” The patient later sees the note where they are dead-named and constantly misgendered and this is upsetting. They worry about returning to the ED.

Questions to consider: Why was this experience upsetting to the patient? What should the resident have done differently? How should he apologize?

Case #2

It is the middle of a quiet shift overnight. You are working alone and see that in room 84 is “Ms. Smith, 20 years old”, here with chief concern of “sore throat”. You walk into her room and say: “Hello Ms Smith!” and look confused because sitting there is a masculine patient with a beard. You are embarrassed by what happened and unsure of how to proceed, realizing this is likely a transmasculine patient that the EMR didn’t relay as such.

- Questions to consider: From here, what do you do and say in the room?

- What could have been done better to prevent this scenario?

- How do you go from here in supporting this patient? Do you apologize? How?

Case #3

A 50yo transfeminine (AMAB) patient with recurrent UTIs presents with dysuria. The UA is positive for pyuria. The well-intentioned EM resident caring for the patient prescribes a 10-day course of cefpodoxime. When the patient asks about the duration and type of antibiotic prescribed, the resident hesitates nervously, then says, “Because your anatomy makes it a complicated UTI”. She later calls to apologize.

Questions to consider: What should this resident have done instead?

The Organ Survey, when relevant:

- “Do you have a Uterus? Ovaries? Cervix/vagina? Penis? Testicles?”

- “What if any surgeries have you had? Top surgery and/or bottom surgery?”

- “Were you assigned male or female at birth?”

Barriers/Challenges/Controversies

This section should help the facilitator anticipate any questions, naysayers, rebuttals, or other feedback they may encounter when presenting the topic and allow preparation with thoughtful responses. Facilitators may experience concerns about their personal ability to present a specific DEI topic (i.e. a white facilitator presenting on anti-racism or minority tax), and this section may address some of those tensions.

Legislation:

- “More than a decade later, Texas concluded the worst legislative session for LGBTQIA+ rights in our history. Beyond the 26 bills attempting to ban transgender kids from playing sports, there were attempts to criminalize parents who support their kids by labeling them as child abusers, efforts to deny youth access to age-appropriate gender-affirming care, and more.” https://www.harpersbazaar.com/culture/features/a38389111/what-it-takes-to-fight-for-trans-kids-in-texas/ (25)

On “messing up” pronouns:

- Commonly-experienced concerns about “messing up” the DEI principle in some way should go, along with any reassurances that would be appropriate https://kconrod.medium.com/pronouns-102-how-to-stop-messing-up-pronouns-9bd66911118 (26)

- “The most important thing to get the pronouns right, and to stop using the wrong pronouns, is repetition and reinforcement. Every time you mess up, you’re reinforcing the pattern you’re trying to break. You have to accumulate more correct pronouns than incorrect ones, and the only way to do that is to get it right a LOT.”

On medical challenges:

- Silicone injections are sometimes undergone by transgender and gender non-conforming patients for the purposes of body contouring, with a reported rate of approximately 16% (27). This is not an FDA-approved use of silicone, and frequently not medical grade silicone, which may result in infections, silicone pulmonary emboli, necrosis, and death (28-31).

Are NB persons transgender?:

- Forty-two percent of non-binary people identify as transgender, thus frequently individuals who are non-binary do not self-identify as being trans (22). Nonbinary individiduals typically have an innate gender that is something other than exclusively man or woman. Their identity could be a combination of both, in-between the two, not having a gender, or having a gender that is outside the man-woman gender spectrum.

Ethical Issues

This section may be useful to hospital ethics committees who want to increase their DEI awareness as part of monthly meetings, or to other groups who are interested in the ethical underpinnings of the topic.

- Given hospital and psychiatric facility beds are scarce, is it ethical to have transgender youth and adults wait longer for beds given their gender identity? Or anyone given their gender?

- Providing hormone blockers for children at 11 and hormones around 14-15 years old, can parents consent? Can children assent? Given how rare it is that individuals stop hormones for identity reasons (as opposed to outside pressures), what are the ethical considerations of providing hormones and blockers to teens?

Opportunities

Sometimes DEI topics can present depressing history and statistics. This section highlights glimmers of hope for the future: exciting projects, areas of study inspired by the topic, or even ironic twists where progress has emerged or may be anticipated in the future.

LGBTQIA+ individuals face health disparities exacerbated by mistreatment, discrimination and social stigma including higher rates of homelessness (33,34), substance abuse (35), depression, anxiety and suicidality (36). Healthy People 2010 identified the need for increased research to document, understand, and address the environmental factors that contribute to these health disparities. An increasing number of health surveys are now collecting information on sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI). Future work should include: prevention of violence toward the LGBTQIA+ community; LGBTQIA+ parenting resources and support; creation of a LGBTQIA+ wellness model; and recognition of transgender health needs as medically necessary. (https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-health) (37)

Journal Club Article links

A journal club facilitator can access several salient publications on this topic below. Alternatively, an article can be distributed ahead of a presentation to prompt discussion or to provide a common background of understanding. Descriptions and links to articles are provided.

Moll J, Vennard D, Noto R, Moran T, Krieger P, Moreno-Walton L, Heron SL. The prevalence of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health education and training in emergency medicine residency programs: Where are we now? AEM Educ Train. 2021 Apr 1;5(2):e10580. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10580. PMID: 33817541; PMCID: PMC8011615. (38) https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/aet2.10580

- The primary objective was to determine how many EM residencies offer education on LGBTQIA+ health. Secondary objectives included the number of actual versus preferred hours of LGBTQIA+ training, identification of barriers to providing education, and correlation of education with program demographics. The majority of respondents offer education in sexual and gender minority health, although there remains a gap between actual and preferred hours. Several barriers still exist, and the content, impact, and completeness of education remain areas for further study.

Samuels EA, Tape C, Garber N, Bowman S, Choo EK. "Sometimes You Feel Like the Freak Show": A Qualitative Assessment of Emergency Care Experiences Among Transgender and Gender-Nonconforming Patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2018 Feb;71(2):170-182.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.05.002. Epub 2017 Jul 14. PMID: 28712604. (19) https://www.annemergmed.com/article/S0196-0644(17)30583-8/fulltext

- Transgender, gender-variant, and intersex (trans) people have decreased access to care and poorer health outcomes compared with the general population. Little has been studied and documented about such patients' emergency department (ED) experiences and barriers to care. Efforts to improve trans ED experiences should focus on provider competency and communication training, electronic medical record modifications, and assurance of private means for gender disclosure.

Lund EM, Burgess CM. Sexual and Gender Minority Health Care Disparities: Barriers to Care and Strategies to Bridge the Gap. Prim Care. 2021 Jun;48(2):179-189. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2021.02.007. Epub 2021 Apr 22. PMID: 33985698. (34) https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0095454321000099?via%3Dihub

- Gender and sexual minority individuals face considerable physical and mental health disparities, health risk factors, and barriers to care. These disparities are rooted in systemic and interpersonal prejudice, discrimination, and violence toward lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and other (LGBTQIA+) individuals and communities that place LGBTQIA+ individuals at increased risk for negative social determinants of health. While also advocating for systemic change, individual providers and clinics have an ethical duty to promote an openly affirming, culturally competent health care environment that can help to address these disparities on an individual patient level.

Discussion Questions

The questions below could start a meaningful discussion in a group of EM physicians on this topic. Consider brainstorming follow-up questions as well.

How do we support gender creative or sexual minority youth who are not “out” to their parents?

- Provide emotional support, create a safe place for dialogue, learn the facts about those identifying as SGMs, screen for bullying, provide resources that the patient can access independently, give yourself extra time to have the opportunity to listen to their concerns (39)

- Be careful to not “out” youth who are not ready. While some parents take the news in stride, others may refuse to support their children - safety first!

How do you approach asking patients for their pronouns, gender identity, and sex assigned at birth? Would you share your own identity or pronouns?

- The easiest way to ask about pronouns is to provide your own. “I am Michelle and I use she/her pronouns. How should I refer to you?” (40)

- Prior work has shown that individuals who identify as a SGM are more comfortable disclosing the sexual orientation and gender identity on a form rather than telling a nurse upon intake to the ED. (41)

- Sex assigned at birth may also be asked on an intake form. If this information is medically necessary, the physician should ask the patient directly.

How do I become an upstander when I hear people say inappropriate things about the trans community or individuals?

- Take action and tell the individual who said something inappropriate to stop or use a tool such as asking, “what do you mean by that?”

- Take action by offering support to the trans individual

- Take action by reporting this behavior to a supervisor

How do I tackle my own bias when it comes to gender non-conforming individuals? What sort of things/ideas that you grew up with need to be addressed to provide better care for trans patients or to work with trans coworkers?

- Take an implicit bias test

- Reflect on your biases

- Be mindful and consider the situation from a different perspective

- Slow down, take the time to think about your words and the impact they will have

- This is a life-long process, so make it a regular focus area of improvement

What are the benefits of providing gender affirming care?

- Gender affirming care saves lives (42)

- Gender affirming allows for an inclusive and positive environment for everyone

- Gender affirming allows for other patients and coworkers, regardless of gender identity, to feel supported and safe in their environment

How do we make a more welcoming environment for LGBTQIA+ folks? (Outside of the rainbow stickers)

- Pronoun pins

- Utilizing intake forms that allow patients to self identify

- Endorsing hospital/clinic policies that support LGBTQIA+ patients and staff, including using primarily single-stall or all-gender bathrooms

- Training all staff in how to specifically care for this population

- Supporting the advancement and recruitment of LGBTQIA+ staff

What policies on a systems level are helpful for creating a more inclusive environment for patients and staff?

- Easily accessible single-stall or ‘gender neutral’/all-gender restrooms and private locker room areas

- Display of a code of conduct within the institution that specifically state transphobic or homophobic language/behavior will not be tolerated

- Creation and ongoing support of LGBTQIA+ affinity group inclusive of all staff

- System level support and engagement in celebrating Pride month (ie, fly the progressive Pride flag, march in the Pride parade, staff the medical tents associated with the Pride parade and festival, set up a booth at your local Pride festival)

- Hospital room assignment policy based on patient’s gender identity in lieu of their sex assigned at birth

How does the EMR affect how I view my patient’s gender identity? How can it be improved?

- Chosen name and pronouns used should be part of the EMR

What are some of the side effects of HRT for both transmasculine and transfeminine patients?

- Side effects of testosterone (for transmasculine patients): risk of obesity, increased LDL levels, polycythemia, infertility, increased CAD risk factors without increase in CAD morbidity/mortality, scalp hair loss, and possible risk of OSA (43,44)

- Side effects of estrogen (for transfeminine patients): risk of DVT/PE particularly in those who smoke, increased risk of CVD, decreased libido, risk of benign pituitary prolactinoma (43,44)

- Side effects of spironolactone (androgen blocker for transfeminine patients): increased urinary frequency, hyperkalemia, hypotension, renal insufficiency (43,44)

What are the benefits of the HRT?

- Allows people to appear and live as their internal self of self, decreases mental health concerns and suicide rates, decreases rates of others identifying individuals as “trans” if that’s not desired (42)

Summary/Take-home Themes

The authors summarize their key points for this topic below. This could be useful to create a presentation closing.

- Gender and sexual minority individuals face considerable physical and mental health disparities, health risk factors, and barriers to care.

- A supportive home and medical environment as well as access to appropriate medical care significantly improve mental health and thus other outcomes for transgender or gender non-conforming individuals.

- Improved allyship and being an upstander can be learned through practice.

Relevant Quotations

Meaningful and relevant quotations (appropriately attributed) can be used to enhance presentations on this topic.

All anonymous quotes from transgender adults (23)

- “About 15 years ago, I was attacked by a stray dog. Upon learning that I was transgender, the ER doctor demanded to see my genitals as part of the exam (the wound btw was on my arm). When I refused, I was sent home to hope and pray I wouldn’t die from infection or rabies. [...] My suggestion for ER staff is to not be so obsessed with seeing patients nude if it’s not relevant to the injury”. -Anonymous

- “I’ve had great experiences in [the ED], they always let me keep my binder and boxers on instead of a gown even for Xrays and CT. I also appreciate when people say “for charting purposes we have to use your legal name/sex, but what name/pronouns do you use so I can add those too?””-Anonymous

- “I’m NB, I had to take my baby to urgent care this weekend. Kept being called ‘mom’. Did not have the spoons to correct everyone. Would have helped if they actually asked pronouns, etc.”-Anonymous

- “There needs to be more implicit bias/assumption training in the medical field. [...] It’s honestly scary to correct medical professionals on things like names, pronouns, and basic information on how hormones work because it’s definitely negatively affected my quality of care before.”-Anonymous

- “Once I had a yeast infection and the doctor told me to stop taking my hormones to make it go away [...] Doctors don’t understand how HRT works at all [...] or believe you”-Anonymous

Specialty Resource Links

Below are links to Emergency Medicine-specific resources for this topic.

ALiEM: Teaching LGBTQ+ Health: 10 Clinical Pearls https://www.aliem.com/teaching-lgbtq-health-10-clinical-pearls/ (45)

Community Resource Links

Below are links to educational resources or supportive programs in the community that are working on this topic.

CDC resource page for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender health. This page includes specific subsections on gay and bisexual men, LGBTQIA+ youth, lesbian and bisexual women, transgender, health services and resources. Within each subsection, there is general information and links to many additional resources. https://www.cdc.gov/lgbthealth/index.htm (46)

Healthy People 2020. Goal: Improve the health, safety, and well-being of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals. This reference contains information on LGBTQIA+ health, multiple resources and references (including peer reviewed articles), and national data and trends. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-health (37)

Video Links

Below are links to videos that do an excellent job of explaining or discussing this topic. Short clips could be used during a presentation to spark discussion, or links can be assigned as pre-work or sent out for further reflection after a presentation.

To Treat Me, You Have to Know Who I am (47)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NUhvJgxgAac

We Are Here: A Transgender Training Video For Healthcare Professionals (48)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X22w0I-RQkQ

Transgender Healthcare Storytime (49)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m9l75EKNYfg

Transgender Healthcare Horror Stories (50)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pvRYamafT0c

Voices of Transgender Adolescents in Healthcare (51)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CHN3YhMi-5A

Simulation Scenario

Below are links to any simulation scenarios available on this topic. Please credit the authors of the simulation if you use their work.

Learning to address implicit bias towards LGBTQIA+ patients: case scenarios

https://www.lgbtqiahealtheducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Implicit-Bias-Guide-2018_Final.pdf (52)

Quiz Questions/Answers

Here are possible questions and an answer key. These can be useful to document effectiveness in learning and knowledge gained but can also be useful to help learners identify that they may not actually know everything about a DEI topic, even if they have participated in presentations on it previously.

- LGBTQIA+ individuals face health disparities exacerbated by mistreatment, discrimination and social stigma including higher rates of homelessness, substance abuse, depression, anxiety and suicidality. (True/False)

- In a 2018 study, almost all EM residents felt comfortable obtaining and H&P on a transgender patient. (True/False)

- Vernacular matching. Match the term with the correct definition.

a. Gender Expression

b. Gender Identity

c. Transgender

d. Gender Nonbinary

e. Gender Nonconforming

f. Sexual Orientation

i. Refers to a person’s sexual attraction to another person and the behavior and/or social affiliation that may result from this attraction (lesbian, gay, bisexual, asexual, etc.)

ii. An individual’s sense of their self as man, woman, transgender, or something else.

iii. The state of one’s physical appearance or behaviors not aligning with societal expectations of their gender (a feminine boy, a masculine girl, etc.).

iv. How an individual chooses to present their gender to others through physical appearance and behaviors, such as style of hair or dress, voice, or movement.

v. Individuals whose current gender identity differs from the sex they were assigned at birth.

vi. Individuals who do not identify their gender as man or woman. Other terms to describe this identity include genderqueer, agender, bigender, gender creative, etc.

Answer Key

- True. LGBTQIA+ individuals face health disparities exacerbated by mistreatment, discrimination and social stigma including higher rates of homelessness, substance abuse, depression, anxiety and suicidality.

- False. In as study by Moll et al (19), EM residents found it challenging to take an H&P on transgender and gender non-conforming patients 42.6% of the time.

- Correct matches are shown below.

a—iv, Gender Expression: How an individual chooses to present their gender to others through physical appearance and behaviors, such as style of hair or dress, voice, or movement.

b—ii, Gender Identity: An individual’s sense of their self as man, woman, transgender, or something else.

c—v, Transgender: Individuals whose current gender identity differs from the sex they were assigned at birth.

d—vi, Gender Nonbinary: Individuals who do not identify their gender as man or woman. Other terms to describe this identity include genderqueer, agender, bigender, gender creative, etc.

e—iii, Gender Nonconforming: The state of one’s physical appearance or behaviors not aligning with societal expectations of their gender (a feminine boy, a masculine girl, etc.)

f—i, Sexual Orientation: Refers to a person’s sexual attraction to another person and the behavior and/or social affiliation that may result from this attraction (lesbian, gay, bisexual, asexual, etc.)

Call to Action Prompt

Below is a statement that inspires participants to commit to meaningful action related to this topic in their own lives. This could be used to prompt reflection, discussion, or could be used in a presentation closing.

As lifelong learners, EM physicians must commit to educating themselves, trainees, and students on SGM health, as well as be supportive of SGM colleagues. EM physicians must commit to creating a supportive and equitable clinical environment for transgender or gender non-conforming individuals to ensure access to appropriate medical care in the context of severe health disparities and poor clinical outcomes for SGM patients.

References

All references mentioned in the above sections are cited sequentially here.

- https://dpcpsi.nih.gov/sgmro

- https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/terminology/sexual-and-gender-identity-terms.htm

- https://www.apa.org/pi/lgbt/resources/sexuality-definitions.pdf

- https://www.ihs.gov/sites/telebehavioral/themes/responsive2017/display_objects/documents/slides/lgbt/lgbtnativeout.pdf

- https://www.dictionary.com/browse/lgbtqia

- https://news.gallup.com/poll/329708/lgbt-identification-rises-latest-estimate.aspx

- Lu, Dave W., et al. "# MeToo in EM: a multicenter survey of academic emergency medicine faculty on their experiences with gender discrimination and sexual harassment." Western Journal of Emergency Medicine 21.2 (2020): 252.

- Hill KA, Samuels EA, Gross CP, Desai MM, Sitkin Zelin N, Latimore D, Huot SJ, Cramer LD, Wong AH, Boatright D. Assessment of the Prevalence of Medical Student Mistreatment by Sex, Race/Ethnicity, and Sexual Orientation. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 May 1;180(5):653-665. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0030. PMID: 32091540; PMCID: PMC7042809.

- Heiderscheit EA, Schlick CJR, Ellis RJ, et al. Experiences of LGBTQ+ Residents in US General Surgery Training Programs. JAMA Surg. 2022;157(1):23–32. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2021.5246

- Hu YY, Ellis RJ, Hewitt DB, et al. Discrimination, abuse, harassment, and burnout in surgical residency training. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(18):1741-1752. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1903759

- Lall MD, Bilimoria KY, Lu DW, et al. Prevalence of Discrimination, Abuse, and Harassment in Emergency Medicine Residency Training in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(8):e2121706. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.21706

- Wheeler, Margaret, et al. "Physician and trainee experiences with patient bias." JAMA internal medicine 179.12 (2019): 1678-1685.

- Dimant OE, Cook TE, Greene RE, Radix AE. Experiences of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary Medical Students and Physicians. Transgend Health. 2019 Sep 23;4(1):209-216. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2019.0021. PMID: 31552292; PMCID: PMC6757240.

- Eliason MJ, Dibble SL, Robertson PA. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) physicians' experiences in the workplace. J Homosex. 2011;58:1355–1371

- https://www.oprahdaily.com/life/relationships-love/a28159555/how-to-be-lgbtq-ally/#:~:text=For%20the%20LGBTQ%20community%2C%20an,face%20greater%20threats%20of%20violence.

- https://www.glaad.org/resources/ally/2

- 2017 AAMC Matriculating Student Questionnaire

- Moravek MB, Baker RM, Marsh EE, Randolph JF. Bridging the gap: national utilization of emergency services by transgender patients. Fertility and Sterility, 2017, Volume 108, Issue 3, Pages e41-e41.

- Samuels EA, Tape C, Garber N, Bowman S, Choo EK. “Sometimes you feel like the freak show”: a qualitative assessment of emergency care experiences among transgender and gender-nonconforming patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2018; 71(2):170-182.

- Moll J, Krieger P, Heron SL, Joyce C, Moreno-Walton L. Attitudes, Behavior, and Comfort of Emergency Medicine Residents in Caring for LGBT Patients: What Do We Know? AEM Educ Train 2019;3(2):129-135.

- Driver L, Adams W, PhD, Dziedzic JM. Attitudes, Behavior, and Knowledge of Emergency Medicine Healthcare Providers Regarding LGBT+ Patient Care, Loyola Medical Center, Emergency Department, WestJEM abstract published, June 2019. https://tinyurl.com/nd82n8y7.

- Trans Student Educational Resources, 2015. “The Gender Unicorn.” http://www.transstudent.org/gender.

- Treating Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Patients in the Emergency Department, Lachlan Driver, MD, HAEMR M&M lecture, November 9, 2021, MGB, Boston, MA

- https://www.lgbtqiahealtheducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Implicit-Bias-Guide-2018_Final.pdf

- https://www.harpersbazaar.com/culture/features/a38389111/what-it-takes-to-fight-for-trans-kids-in-texas/

- https://kconrod.medium.com/pronouns-102-how-to-stop-messing-up-pronouns-9bd66911118

- Nolan, Ian T et al. “Demographic and temporal trends in transgender identities and gender confirming surgery.” Translational andrology and urology vol. 8,3 (2019): 184-190.

- Visnyei K, Samuel M, Heacock L, Cortes JA. Hypercalcemia in a male-to-female transgender patient after body contouring injections: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014 Feb 26;8:71.

- Jilani N, Shabbir J, Nemytova E. Liquid silicone-induced extensive and debilitating granulomatosis responding to hydroxychloroquine. Case Rep Rheumatol. 2019 Jul 24;2019:8173790.

- FDA. The FDA warns against injectable silicone for body contouring and enhancement. (Accessed September 16, 2021, at https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/fda-warns-against-injectable-silicone-body-contouring-and-enhancement

- Wilson E, Rapues J, Jin H, Raymond HF. The use and correlates of illicit silicone or "fillers" in a population-based sample of transwomen. J Sex Med. 2014 Jul; 11(7):1717-24.

- Wilson BDM, Meyer IH. Nonbinary LGBTQ adults in the United States. Los Angeles: The Williams Institute, (Accessed October 3, 2021) https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/nonbinary-lgbtq-adults-us

- Lim FA, Brown DV, Kim SMJ. Addressing health care disparities in the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender population: a review of best practices. Am J Nurs. 2014; 114(6)24-34. PMID 24826970

- Lund EM, Burgess CM. Sexual and Gender Minority Health Care Disparities: Barriers to Care and Strategies to Bridge the Gap. Prim Care. 2021 Jun;48(2):179-189. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2021.02.007. Epub 2021 Apr 22. PMID: 33985698.

- Caceres BA et al. A Systematic Review of Cardiovascular Disease in Sexual Minorities. Am J Public Health. 2017;107:e13-e21. PMID: 28207331

- Cochran SD, Mays VM, Sullivan JG. Prevalence of mental disorders, psychological distress, and mental health services use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(1):53–61. PMID: 12602425

- https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-health

- Moll J, Vennard D, Noto R, Moran T, Krieger P, Moreno-Walton L, Heron SL. The prevalence of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health education and training in emergency medicine residency programs: Where are we now? AEM Educ Train. 2021 Apr 1;5(2):e10580. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10580. PMID: 33817541; PMCID: PMC8011615

- https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/wellness-and-prevention/tips-for-parents-of-lgbtq-youth

- https://www.mypronouns.org/asking

- Haider AH, Schneider EB, Kodadek LM, et al. Emergency Department Query for Patient-Centered Approaches to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity : The EQUALITY Study. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(6):819-828. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0906

- https://www.columbiapsychiatry.org/news/gender-affirming-care-saves-lives

- https://fenwayhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/Friday-Session-5a.pdf

- https://www.lgbtqiahealtheducation.org/wp-content/uploads/COM-2245-The-Medical-Care-of-Transgender-Persons-v31816.pdf

- https://www.aliem.com/teaching-lgbtq-health-10-clinical-pearls/

- https://www.cdc.gov/lgbthealth/index.htm

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NUhvJgxgAac

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X22w0I-RQkQ

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m9l75EKNYfg

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pvRYamafT0c

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CHN3YhMi-5A

- https://www.lgbtqiahealtheducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Implicit-Bias-Guide-2018_Final.pdf