DEI Definitions: Defining Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) and Strategies to Implement DEI Education

Foundational Definitions to Guide Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) Discussions and Strategies to Incorporate DEI Education in Medical Training Programs

Author(s): Samreen Vora, MD, MHAM, FACEP and Kristyn J. Smith, DO

Editor: Christine Stehman, MD

Definition(s) of Terms

Starting with a common understanding of key words, phrases, and potentially misunderstood related terms in DEI discussions helps ensure that all participants feel informed and welcome to participate in the discussion. Some terms have multiple definitions provided to help highlight nuances in the definitions.

- Diversity: “Diversity refers to anything that sets one individual apart from another, including the full spectrum of human demographic differences as well as the different ideas, backgrounds, and opinions people bring.” (1)

- Equity: Being fair and impartial;

“Equity is the guarantee of fair treatment, advancement, opportunity and access for all individuals while striving to identify and eliminate barriers that have prevented the full participation of some groups and ensuring that all community

members have access to community conditions and opportunities to reach their full potential and to experience optimal well-being and quality of life.” (1)

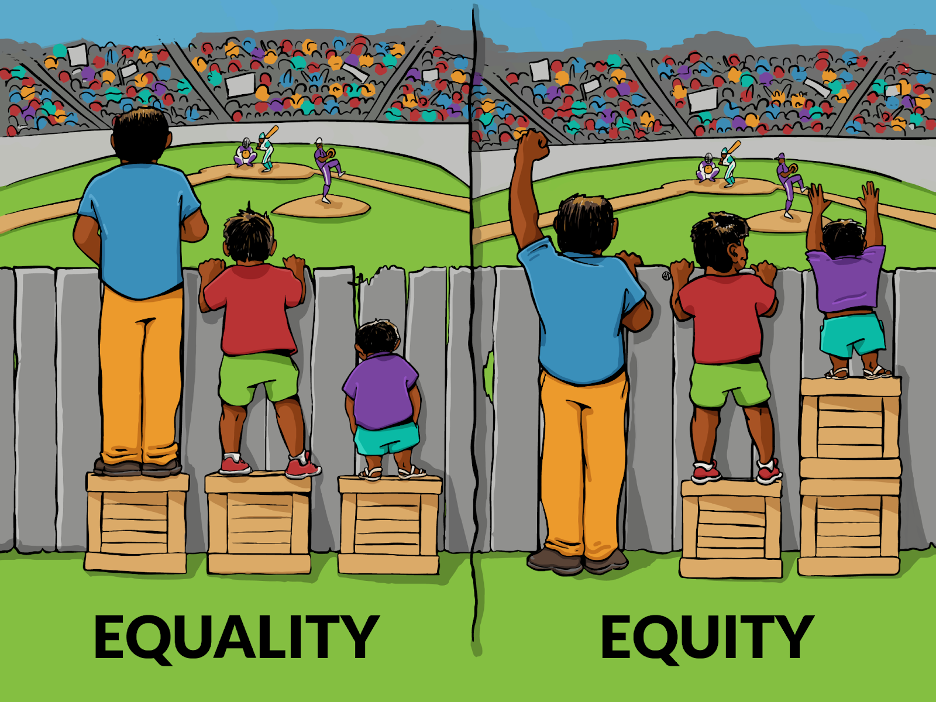

- Equity versus equality: Equality is providing the same to all. Equity recognizes differences in starting points and adjusts resource allocation to reach an equal outcome. In other words, with equality everyone has the same and with equity everyone

has what they need. (2)

- Inclusion: Re-distributing power by authentically bringing traditionally excluded individuals and/or groups into processes, activities, and decision making.

Synonyms/Related Terms

This section highlights the definitions of other words that may be used in discussion of this topic. Sometimes these words can be used interchangeably with the terms defined above, and sometimes they may have been used interchangeably historically, but have distinct meanings in DEI conversations that it is helpful to recognize.

Commonly Used Abbreviations:

DEI - Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

DIB - Diversity, Inclusion, and Belonging

D&I - Diversity and Inclusion

E&I - Equity and Inclusion

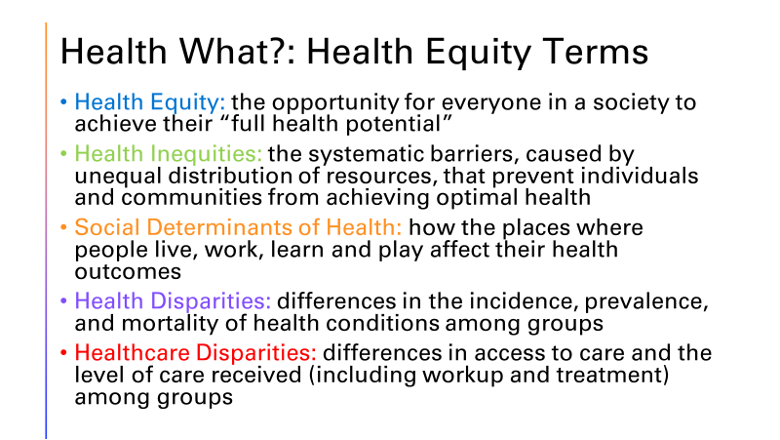

Health Equity

JEDI - Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

Related Terms:

Anti-Racism: “The active process of identifying and challenging racism, by changing systems, organizational structures, policies and practices, and attitudes, to redistribute power in an equitable manner.” (1)

BIPOC: Black, Indigenous, People of Color

Bystander: a person who witnesses a situation but does not partake in the situation

Cisgender: when one’s gender identity and sex assigned at birth are the same

Cultural Competence: demonstrated behaviors, attitudes, policies, and structures that enable individuals and/or organizations to work effectively cross-culturally. (3) It is important to note that ‘cultural competence’ is no longer a preferred term; one cannot ever be ‘competent’ in any culture. The focus is rather on developing a set of communication skills that exhibit cultural humility. See definition of ‘cultural humility’ below.

Cultural Humility: is the “ability to maintain an interpersonal stance that is other-oriented (or open to others) in relation to aspects of cultural identity that are most important to the [person].” (1)

Gender expression: how a person chooses to express their gender to the external world

Gender identity: how a person internally identifies with a gender

Health disparities: differences in the incidence, prevalence, and mortality of health conditions among groups

Healthcare disparities: differences in access to care and the level of care received (including workup and treatment) among groups

Health equity: the opportunity for everyone in a society to achieve their “full health potential”

Health inequities: the systematic barriers, caused by unequal distribution of resources, that prevent individuals and communities from achieving optimal health

Homophily: the tendency for people to gravitate towards others who they are similar to (whether this be by race/ethnicity, primary language spoken, gender identity, sexual orientation, etc.)

Identity: how one sees themselves in the world

Intersectionality: the idea that each individual has multiple identities, and this affects their experiences of discrimination and privilege. This term was created in 1989 by Professor Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989. (4)

Justice: Removing the barriers that prevent equity; fixing systems to provide access to resources and opportunities

Linguistic Competence: capacity of an organization and its personnel to communicate effectively, and convey information in a manner that is easily understood by diverse groups including persons with ‘non-English language preference’ (previously referred to as limited English proficiency), those who have low literacy skills or are not literate, individuals with disabilities, and those who are deaf or hard of hearing. (5)

Microaggression: verbal, non-verbal, and systemic insults that ultimately invalidate the experiences of marginalized communities, specifically people who identify as women, racial/ethnic minorities, and/or LGBTQIA+, which supports maintenance of existing power structures. (6)

Micro-aggressor: a person who commits a microaggression, whether intentional or unintentional

Non-binary: gender identities other than “male” or “female”

Privilege: advantages a person has in society that allow more favorable treatment or outcomes

Sex assigned at birth: the gender assigned to a person at birth, based on external genital anatomy

Social Determinants of Health (SDoH): how the places where people live, work, learn and play affect their health outcomes

Upstander: a person who witnesses a macro- or micro-aggression and then acts to speak up on behalf of the person who is being discriminated against

The following table from Vora et al (7) offers additional core definitions as they relate to DEI education.

| Term | Definition | As defined by: |

| Structural/Systemic Racism | Differential access to the goods, services, and opportunities of society by race. Pervasive set of societal and interpersonal practices within and outside healthcare institutions that foster discriminatory practices to create systematic disadvantage and health inequities in a racial group. | Camara Jones, 2000 Doubeni and colleagues, 2021 |

| Institutional Racism | The policies and practices within and across institutions that, intentionally or not, produce outcomes that chronically favor, or put a racial group at a disadvantage. | The Aspen Institute, 2020 |

| Personally Mediated Racism | Prejudice and discrimination, where prejudice means differential assumptions about the abilities, motives, and intentions of others according to their race, and discrimination means differential actions toward others according to their race. | Camara Jones, 2000 |

| Internalized Racism | Acceptance by members of the stigmatized races of negative messages about their own abilities and intrinsic worth. | Camara Jones, 2000 |

| Implicit/Unconscious Bias | Implicit bias is defined as unconscious attitudes toward a person, group, or idea which often result in discriminatory behaviors and can often differ from explicit or expressed beliefs. | Fazio and colleagues, 2003 Hagiwara and colleagues, 2020 |

| White Fragility | “state in which even a minimum amount of racial stress becomes intolerable, triggering a range of defensive moves” | Robin DiAngelo, 2011 |

| White Privilege | White peoples’ historical and contemporary advantages in access to quality education, decent jobs and liveable wages, homeownership, retirement benefits, wealth and so on. | The Aspen Institute, 2020 |

| White Urgency | White people newly finding the need to speak out against racial injustice and actively dismantling structural racism as urgent while people of color have been leading and working in racial justice movement for decades. | Beth Berila, 2020 |

| Microaggressions | “Racial microaggressions are brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial slights and insults toward people of color.” “Microaggressions seem to appear in three forms: microassault, microinsult, and microinvalidation.” | Sue and colleagues, 2007 |

| Stereotypes | “Cognitive schemas, often rooted in culturally held beliefs that are used by social perceivers to process information about others.” Stereotypes are most often negative versus an ‘archetype’ used to describe basic characteristics. | James Jones |

| Prejudice | “An attitude that represents generalized feelings toward and evaluation of a group or its members and can result in discriminatory behavior or behavioral intentions.” | John Dovidio and James Jones, 2019 |

| Discrimination | Discrimination refers to the unequal treatment through an action or inaction based on one’s physical characteristics or perceived social group assignment. | Davis, BA James Jones |

Scaling This Resource: Recommended Use

As many users may have varying amounts of time to present this material, the authors have recommended which resources they would use with different timeframes for the presentation.

The Trusted 10 Activity [The-Trusted-10-Exercise.pdf (sloverlinett.com)]

1-5 minute activity: first part of prompt in the section or “Trusted Ten” (all levels)

10-15 minute activity: both prompts in this section (all levels)

10-15 minute activity: discussion on the first image (all levels)

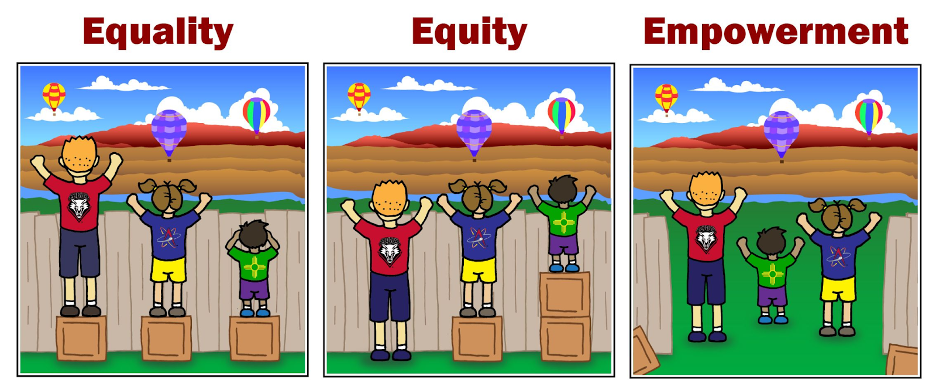

30 minute activity: discussion on 3 equity/equality/empowerment images (residents and attendings, some students may be able to do this). Use suggested discussion questions.

Either of these could be done as a group discussion or as a “Think/Pair/Share” to

make it more intimate.

60 minute activity: review definitions, consider (Think/Pair/Share) what they bring up, Trusted Ten, review of one or both images

60 minute activity: journal club on 1 or both articles.

Discussion/Background

This section provides an overview of this topic so that an educator who is not deeply familiar with it can understand the basic concepts in enough detail to introduce and facilitate a discussion on the topic. This introduction covers the importance of this topic as well as relevant historical background.

Definitions of diversity abound. At the most basic level, diversity is a variety of unique characteristics. In anthropology, diversity is understood in the context of humans creating ‘social borders’. (8) Social borders are human constructs and can include aspects such as race, ethnicity, and language. Social borders exist in varying degrees and levels depending on circumstances. For example, in early United States (US) history, ‘race’ was a social construct created to justify chattel slavery. (9,10) In healthcare, the concept of diversity is usually in reference to patient demographics (e.g., race, ethnicity, age, gender identity, sexual orientation, income level, etc). In medical education, diversity is generally focused on comparison of US physician demographics to the demographics of the US population as a whole. More recently, efforts have been made to expand beyond the narrow focus of diversity to equity and inclusion. Equity is access to resources and services that gives everyone within a society, organization, or training program the opportunity to reach their full potential. Inclusion is the creation of environments that allow for the unique characteristics of all individuals to be acknowledged, supported, and celebrated. It is at the cross-section of these terms that medical education training programs and healthcare systems should aim to operate.

‘Cultural competence’ has also been a commonly used term in medical education. In 1989, Cross et. al, coined the term ‘cultural competence’, which referred to demonstrated behaviors, attitudes, policies, and structures that enable individuals and/or organizations to work effectively cross-culturally. (3) Since the development of this term, literature related to creating diverse, equitable, and inclusive healthcare environments has grown, resulting in an evolution in terminology. For example, there is a move away from cultural ‘competence’ to cultural humility. Acknowledging that in emergency medicine, and healthcare professional training in general, the word ‘competence’ is often used to indicate mastery of a technical skill. When related to cultural understanding, use of the term ‘competence’ can be harmful as it implies an end-goal. Also, ‘competency’ does not account for cultures being made up of unique individuals and the changing of cultures over time. Lastly, and most importantly, one cannot ever be ‘competent’ in any culture. The focus is rather on developing a set of communication skills that enable effective cultural humility. There is a shift to skill-building and advocacy training that incorporates antiracism, addressing microaggressions through upstander training, and managing implicit biases. Acquisition of these skills is critical for emergency providers as this directly impacts patient care and outcomes.

Understanding health disparities allows us to shift from prioritizing equality to promoting equity. Health disparities impact those groups and identities who have been most impacted by structural racism and discrimination, in particular those who have been historically and deliberately disenfranchised and marginalized. To appropriately address health and healthcare disparities, we need to focus on the needs of these groups and identities more so than those not affected. Many national organizations have made a call to action over the last decade (11-14) to reduce health disparities, and there is still room for us to do better.

Part of this call to action includes diversifying the physician workforce. According to estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau, racial/ethnic minorities are expected to be the majority in the United States by 2042.(15) Currently, the diversity of the emergency medicine physician workforce does not reflect the diversity of the general population. Studies show that physicians who identify as under-represented in medicine (UiM) bring varied life experiences, diversity of thought and improved patient outcomes. (16-18) There is also recent data noting better patient health outcomes when there is concordance of race between physicians and patients.(19) Furthermore, gender concordance also has a positive effect on patient health outcomes, such as more intense chronic disease management and reduced mortality for patients who identify as women when treated by women physicians. (20) In addition, many physicians who identify as UiM go on to practice in medically and socioeconomically under-resourced areas, which helps to ensure access to care for marginalized communities.(21) Lastly, for individual emergency departments, recruitment of diverse faculty helps to continuously propel diversity efforts and allows for continued retention and recruitment of diverse physicians. (22) This is not only a call to diversify the physician workforce, which based on the statistics is still needed, but for all of us to better understand our roles in this data and provide equitable care.

Part of our role in providing equitable care includes education, both educating ourselves and the next generation of emergency medicine physicians. Included in the remainder of this review are resources, with suggested learning activities, that can assist your program in incorporating multi-modal, longitudinal health equity education into your current curriculum. Many of the resources can be scaled-up or down depending on resource and time allotment.

Quantitative Analysis/Statistics of note

This section highlights the objective data available for this topic, which can be helpful to include to balance qualitative or persuasive analysis or to help define a starting point for discussion.

Using 2021 AAMC data, out of 8,300 Medical Doctor (MD), Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (DO), and International Medical Graduate (IMG) emergency medicine residents, 62.8% identified as male and 37.2% as female (notably there was no category for gender non-binary residents).(23-27) Furthermore, approximately 68% of EM residents identified as White, 15% Asian or Pacific Islander, 8% Latinx, 6% Black or African-American, 4% did not self-identify a race/ethnicity or marked ‘other’, less than 1% American Indian/Indigenous American. (23-27) The most recent emergency medicine attending physician workforce data in 2018 shows that out of 43,748 emergency medicine physicians 72% were male and 28% were female (again there were no other gender categories offered).(28) Amongst this cohort, about 69% were White, 10% Asian or Pacific-Islander, 9% did not self-identify a race/ethnicity, 5% Latinx, 5% Black or African-American, 1% multi-racial/ethnic, and less than 0.5% American Indian/Indigenous American. (28) According to the 2020 US Census, 49% of the US population identifies as male and 51% as female. (29) In the US, 62% of the population identifies as White, 19% Latinx, 12% Black of African American, 6% Asian or Pacific Islander, 1% American Indian/Indigenous American, 10% multiracial/multiethnic (includes double counting given some respondents respond to both race and ethnicity categories).(30) These statistics underscore the need for continued recruitment and retention of diverse emergency medicine physicians. We recommend using these statistics as the justification and foundation for development of recruitment strategies which prioritize diversity, exemplifying the mis-match between the diversity of the emergency medicine physician workforce and current US population.

Some departments include DEI in their departmental administration and resident education. Administratively, a few emergency departments throughout the country have specific DEI positions, such as Chair, Vice Chair, or Department Lead of DEI, aimed at strengthening departmental efforts related to recruitment, retention, promotion, and inclusion of a diverse emergency physician workforce. Educationally, DEI has expanded from a narrow focus on patient-experienced health disparities to include a large breadth of topics which can include training on the social determinants of health, racial/ethnic and gender identity, medical racism, antiracism, care for patients with non-English language preference, pain management disparities, patient first communication skills, and implicit bias.

Developed in 2001 and updated every two years, The Model of the Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine provides a framework for the core competencies of emergency medical care. The Model specifies knowledge of “cultural competency, health disparities, social determinants of health, gender identity and sexual orientation, and transgender care” as core competencies. (31) Unfortunately, there are limited data on the implementation of training related to these core competencies. In 2017, Mechanic et. al found that approximately 69% of emergency medicine residency programs that completed a national survey through the Council of Residency Directors in Emergency Medicine (CORD), incorporated cultural competency education into their curricula. (32) Based on that survey the content of this education was limited with 86% of programs including education on race/ethnicity and only 40% of programs including content related to caring for patients with ‘non-English language preference’. (32) If we use this survey as a foundation of what may be happening related to DEI education, it can be hypothesized that most DEI-related education is quite narrow in focus and does not begin to cover the broad depth of potential DEI-related content.

Slide Presentation or Images

Images and graphical representations in presentations can clarify concepts and enhance interest. Please cite the sources of these images appropriately if you use them in your presentation, found in the last section of this page. We purposefully avoided providing complete slide decks in this curriculum, and instead opted to offer easy building blocks for a great personalized presentation regardless of the format.

Slide 1: Defining health equity. Definitions based on information from the World Health Organization and American Public Health Association. (33-34) Slides 1-2 give a basic review of health equity terms, which is applicable for learners at all levels.

Slide 2: Historically marginalized identities. Slides 1 and 2, above, can be used when presenting foundational components of DEI-related education. Slides 1 and 2 give a basic review of health equity terms, which is applicable for learners at all levels.

Equity vs. Equality vs. Empowerment Learning Activity (Images 1-3).

Image 1. Citation: © Interaction Institute for Social Change | Artist: Angus Maguire

Vs

Image 2. Citation:“Office of Equity and Inclusion.” The City of Albuquerque, <https://www.cabq.gov/office-of-equity-inclusion>

Image 3. Citation: Barceló, N.E., Shadravan, S. Race, Metaphor, and Myth in Academic Medicine. Acad Psychiatry 45, 100–105 (2021).

Discussion Questions for Equity vs. Equality vs. Empowerment Learning Activity

Consider discussion around these three images.

Questions for group to consider when viewing the 3 artist renderings of Equity:

- How do these images make you feel?

- How are your feelings similar or different as you look at each of the 3 images?

- For image 3, how does this image represent our current society and the impact of systemic racism?

- For image 2, how can you bring the concepts represented in this image to your practice? How can you move towards empowerment in your current practice?

The first image is a very common one used to explain equity versus equality. It is a start but as we’ve learned more about equity, many will look at this image and recognize it is not sufficient. For a higher level discussion, consider discussing the second and third images for a comparison. Utilize the suggested questions to prompt learners to think about the systems around them and their own role in promoting equity. The first image indicates an inherent difference in the individual or even a shortcoming in individuals, whereas the third one better depicts the systemic aspects of racism and inequity. Equally able individuals are hampered by an inequitable and racist system.

Role-playing Scenario

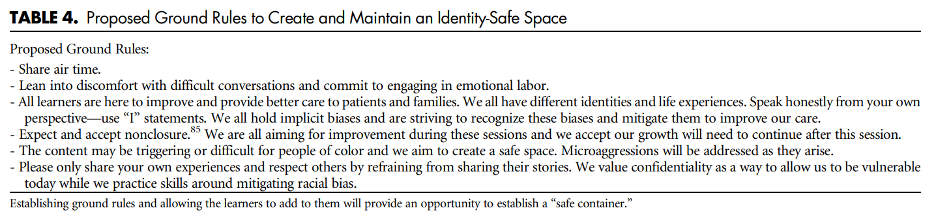

Role-playing scenarios can enhance investment and participation. Always consider psychological safety when asking participants to engage in any role-playing activity to avoid potential adverse effects. We highly recommend a discussion for each group to agree on ground rules of respectful learning prior to engaging in any role-playing scenarios (embrace ambiguity, commit to learning together, listen actively, create a brave space, suspend judgment, etc.). It is reasonable to review these ground rules prior to each role-playing discussion.

When having DEI discussions, there is potential to do harm despite good intentions. (35,36) It is imperative to have the facilitator or faculty set clear ground rules prior to facilitating any session, see below for an example. Leaders of DEI education within your program must have done their own education in this area to reduce their likelihood of unintentionally causing harm. Facilitators must also be mindful of the impact their words can have on learners during these discussions. Faculty should consider completing their own training on facilitating difficult discussions and review the other SAEM modules available on topics such as Allyship/Upstander/Bystander, Microaggressions/Macroaggresions/Microinsults, and Bias:Implicit vs Explicit, and Discrimination. Other content related to facilitator training is included in our Barriers/Challenges/Controversies section below.

15 min activity:

Take a moment to reflect on how you feel when someone mentions ‘diversity’. Do you think ‘oh no, not again?’, do you think ‘yes, we need to discuss this so others can learn’, or what other thoughts do you think? Just reflect on why you may be having these thoughts and reactions. It is easier to think the problem is outside yourself, but take a moment to practice a bias mitigation strategy of “Mindfulness” to identify what is happening within yourself. Consider learning more about implicit bias mitigation strategies to uncover your own biases and change your behaviors at the bedside to provide more equitable care. (37,38).

Next, consider completing the Trusted Ten activity [The-Trusted-10-Exercise.pdf (sloverlinett.com)]. A quick version of this activity could be to take a moment and think of the ten people that are closest to you. Write down or reflect on what identities they hold (sex, gender, religion, race, ethnicity, marital status, etc). How many of the identities intersect with your identities, where is there diversity in your closest relationships? Where is there a gap in representation? How might you expand your circle so you can learn different perspectives making it easier to practice the bias mitigation strategy of “Perspective Taking”.Barriers/Challenges/Controversies

This section should help the facilitator anticipate any questions, naysayers, rebuttals, or other feedback they may encounter when presenting the topic and allow preparation with thoughtful responses. Facilitators may experience concerns about their personal ability to present a specific DEI topic (ie a white facilitator presenting on anti-racism or minority tax), and this section may address some of those tensions.

Q: The residency program associated with my emergency department is already struggling to find time to teach the core clinical competencies needed for graduation. How can I incorporate another educational domain related to DEI?

Every US-based emergency medicine residency program is already using a multimodal approach for resident teaching including bedside rounds, journal clubs, case simulations, and lecture-based didactics. To highlight the foundational role health equity plays in all aspects of clinical care, we would suggest interweaving DEI-related education into simulations and didactics that are already being taught. For instance, faculty could be required to update their current didactics to include education about the social determinants of health, healthcare disparities, cultural and linguistic competency, systemic racism, and antiracism. See Supplemental Digital Content resource list of Vora et al article for a start for facilitators to do self-development as they incorporate these concepts into their lessons. (7) This allows for all faculty to be involved in DEI-education and underscores the importance of these topics to every section of the medical curriculum. However, until a standard can be developed it may be easier for some programs to implement distinct DEI-related education. There is an Anti-Racism in Medicine Collection on MedEdPortal. (MedEdPORTAL) Throughout this document are several resources that highlight novel approaches to DEI-related resident education, with suggestions for implementation. It is important to note that this document is not exhaustive, but is a good starting point to begin skills-based DEI-education within your training program.

Q: How do I initiate or facilitate DEI sessions or content when I am not a DEI expert?/ How do I initiate or facilitate DEI sessions or content when I am not a person of color? Like all aspects of medical education, DEI is best taught by experts who have specific training in DEI-related topics. For many physicians who come from marginalized communities, expertise comes in the form of lived experiences in addition to formal courses and training. It is important that institutions be mindful to choose diverse leaders in all clinical aspects, including, but not limited to, DEI-related efforts. Furthermore, it is important for individuals to do their own personal work to be prepared to lead DEI education as there is great potential to do harm. There are a variety of resources for individuals to personally grow in this area and should be considered as facilitator pre-work. A brief, not exhaustive, list of resources is provided as part of supplemental digital content in the Vora et al article. (7) In particular, it is important for White people to understand their own capacity for ‘White fragility’ as they engage in this work and lead others.(39) Do not shy away from doing this work out of fear of being uncomfortable but lean in deliberately, with humility, and recognize it is a personal journey not a destination.

Q: Learners may ask why there is a focus on a certain group or identity in a DEI session.

Recently, as diversity is being discussed more often, a common question is “why are we focused on a certain ‘group’ or ‘identity’ over another”. Data and experience demonstrate that ‘centering at the margins’ improves experiences for all and in order to do this we must understand the issues of those in the margins. Dr. Ford and Dr. Airhihenbuwa explain, “To center in the margins is to shift a discourse’s starting point from a majority group’s perspective, which is the usual approach, to that of the marginalized group or groups.” (40) So although understanding the importance of various forms of diversity is critical, consider who are those that are most impacted by health and health care disparities. This may vary based on your local organization’s needs. In the national context in the US, the historical disenfranchisement of the Black and Native American populations via chattel slavery and colonization have consistently placed them at the margins. When we do better at the margins, we do better for all, and our disparities data indicates we have a long way to go.

Opportunities

Sometimes DEI topics can present depressing history and statistics. This section highlights glimmers of hope for the future: exciting projects, areas of study inspired by the topic, or even ironic twists where progress has emerged or may be anticipated in the future.

The murder of George Floyd accelerated DEI discussions and initiatives around the country. This is an opportunity where the nation is leaning in on antiracism and DEI. More people appear willing to be vulnerable in an effort to make progress. This shared experience offers a glimmer of hope, but much of the rallying behind DEI initiatives may be performative. DEI work has to be internalized and systematized for it to produce useful deliverables.

Journal Club Article links

A journal club facilitator can access several salient publications on this topic below. Alternatively, an article can be distributed ahead of a presentation to prompt discussion or to provide a common background of understanding. Descriptions and links to articles are provided.

The purpose of journal clubs are to critically assess literature to remain up-to-date on new medical findings and discuss how to apply new procedures and knowledge to current practices. Implementation of health equity education can be achieved by developing a review of how to develop a health-equity focused journal club within your training program. While the subsequent articles can be used to discuss how bias can affect health outcomes and brainstorm ways to mitigate these biases.

| Title of Article/Content Source | Article/Content Source Description | Sample Discussion Points and Questions for Journal Club Sessions |

| Racial Bias in Pulse Oximetry Measurement (41,42) | This letter to the editor describes evidence of racial bias in pulse oximetry measurement. A study was performed examining paired pulse oximetry measured oxygen saturation and measures of arterial oxygen saturation obtained via arterial blood gases to assess for occult hypoxemia, defined as an arterial oxygen saturation less than 88% despite an spO2 of 92-96%. Results showed Black patients had almost three times the rate of occult hypoxemia as White patients. |

|

| Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between Blacks and Whites (43) | A study performed asked American-born, English as their first language, non-Latinx White medical students years 1-3 and residents to rate their agreement of 15 biological differences between Whites and Blacks. The study survey included 11 untrue differences (“falsities”) and 4 true differences (as supported by research). 50% of all respondents, regardless of year in training, endorsed at least one falsity regarding biological differences between Blacks and Whites. For example, almost 60 percent of all respondents, regardless of year in training, agreed that “Black people have thicker skin than White people”. |

|

| Addressing Implicit Bias in Nursing: A Review (36) | This article examines the nature of implicit, or unconscious, bias and how such bias develops. It describes the ways that implicit bias among health care providers can contribute to health care disparities and discusses strategies that can be used to recognize and mitigate any biases one may have. |

|

Discussion Questions

The questions below could start a meaningful discussion in a group of EM physicians on this topic. Consider brainstorming follow-up questions as well.

These discussion questions can be used with the “Related terms” section above to further discuss core terms related to DEI.

Interprofessional Group Question

Q: What does diversity mean to you?

Q: What words would you use to describe your identity?

This can be turned into a group activity where learners write down several self-identifying characteristics (e.g., age, race/ethnicity, likes/dislikes, place of birth, etc.). Learners then pair up and write down all the characteristics they would use to describe their partner. Learners then swap characteristics lists and get to see how much of one’s identity is “skin deep” or beyond things you can see like gender expression, race/ethnicity, primary language spoken.

Q: What would be an ideal way to learn more about diversity?

Q: What have you seen in relation to these issues within your school/class/department? (Allow for participants to share personal experiences if desired but do not put the onus on those that may be from an underrepresented group to teach the group or share)

Summary/Take-home Themes

The authors summarize their key points for this topic below. This could be useful to create a presentation closing.

- Diversity, equity, and inclusion is essential to quality emergency medical care.

- Diversity, equity, and inclusion is essential to maintain an engaged and effective workforce.

- Concepts related to health equity can be taught in many ways.

- Considering your own personal role in improving health care inequities is critical.

- Everyone within an emergency department is personally responsible for fostering an inclusive environment where diversity is sought out, supported, and valued.

Relevant Quotations

Meaningful and relevant quotations (appropriately attributed) can be used to enhance presentations on this topic.

- “Diversity is a fact, but inclusion is a choice we make everyday. As leaders, we have to put out the message that we embrace, and not just tolerate, diversity.” - Nellie Borrero

- “A diverse mix of voices leads to better discussions, decisions, and outcomes for everyone.” - Sundar Pichai

- “In the end, as any successful teacher will tell you, you can only teach the things that you are. If we practice racism then it is racism we teach.” - Max Lerner

- “All of us in the academy and in the culture as a whole are called to renew our minds if we are to transform educational institutions-and society – so that the way we live, teach, and work can reflect our joy in cultural diversity, our passion for justice, and our love of freedom.” - Bell Hooks

Specialty Resource links

Below are links to Emergency Medicine-specific resources for this topic.

Also included are examples for how to implement educational content related to each resource.

- McMichael B, et al. The Impact of Health Equity Coaching on Patient's Perceptions of Cultural Competency and Communication in a Pediatric Emergency Department: An Intervention Design. (44)

- Summary of Resource: The article discusses an intervention used to increase awareness of implicit bias and health disparities experienced by Indigenuous children and their families.

- Suggested Ideas for Implementation:

- Using the outlined lecture content in the article, your program could develop similar educational lectures. Ideally, the education would be related to the patient populations most often served by your practice.

- Service learning opportunities aimed at community engagement could be developed for your practice.

- Smith KJ, et. al. Development of a health equity journal club to address health care disparities and improve cultural competence among emergency medicine practitioners. (45)

- Summary of Resource: Article outlines the process of developing and implementing a journal club related to health equity at a large, academic-community emergency medicine residency program.

- Suggested Ideas for Implementation:

- Using the structure outlined in the article a health equity journal club could be started within your residency program. The journal club could be developed by a resident, with support from a faculty advisor.

- If a separate DEI-focused journal club cannot be implemented, articles related to health equity should be incorporated into your current journal club curriculum. Your program should include educational material related to racial bias in pulse oximetry measurement (41-42), pain management disparities (46), microaggressions experienced by physicians who are UiM, etc. Education about these topics exemplify how bias causes disparate ED care. Additionally, discussions that illuminate differential treatment experienced by non-male, non-White colleagues can begin the process towards a more inclusive environment. See journal club section for additional potential journal club articles.

- Chary AN, et al. Addressing Racism in Medicine Through a Resident-Led Health Equity Retreat. (47)

- Summary of Resource: A 3-hour retreat, held during mandatory residency didactic conference, in which residents participated in sessions about experiences of racism in the ED, microaggressions, and how physician bias affects the care of agitated patients. Preliminary data showed that “all participants reported improved understanding of diversity within the workplace and the majority found the retreat sessions to be helpful to their clinical practice”.

- Suggested Ideas for Implementation:

(1) Using the article as guidance a similar retreat could be held at your institution. A summary of each of the three retreat sessions are listed below:

(2) Session 1: Prior to the retreat participants were asked to anonymously submit instances of racism they had experienced. During the retreat a discussion about specific forms of racism, using the submitted examples, took place.

(3) Session 2: Participants were split into pairs, with each participant of the pair being a different racial and/or ethnic group. Specific examples of microaggressions are telling a person of color “you’re so well spoken”, confusing one person or color for another, or telling a woman “you’re too pretty to be a doctor” (not from the article). Each participant shared their experiences with these statements and their negative impact.

(4) Session 3: A panel of ED attendings, social workers, and psychiatrists discussed their experiences with caring for agitated patients. Literature that highlights how patients from minority groups have a higher rate of security calls and use of restraints was reviewed. A resident-created algorithm for unbiased de-escalation techniques was presented.

- While a half- or full-day retreat would be preferable, each one of the sessions above could be implemented monthly, bi-monthly, or quarterly. This would allow for longitudinal education related to microaggressions and implicit bias management.

- Suggested Ideas for Implementation:

- Summary of Resource: A 3-hour retreat, held during mandatory residency didactic conference, in which residents participated in sessions about experiences of racism in the ED, microaggressions, and how physician bias affects the care of agitated patients. Preliminary data showed that “all participants reported improved understanding of diversity within the workplace and the majority found the retreat sessions to be helpful to their clinical practice”.

- Zeidan AJ, et al. Implicit Bias Education and Emergency Medicine Training: Step One? Awareness. (48)

- Summary of Resource: An educational intervention designed to increase residents’ awareness of their own implicit biases based on race was implemented. The intervention included a grand rounds lecture about implicit bias, time to take the Harvard Implicit Association Test (IAT) on race (49), and a 50 minute debrief discussion about results. The intervention had positive outcomes, with participants’ awareness of their own implicit biases increased by 33% and awareness of how their IAT scores influenced patient care by 9%.

- Suggested Ideas for Implementation:

- Use the article as a roadmap to create a similar implicit bias training for your residency.

- Introduce short implicit bias lectures into didactic time. This may take the form of allowing trainees to take one of the Harvard Implicit Association Tests (IAT) during conference time. Followed by a brief discussion of their results and ultimately a review of bias mitigation techniques.

- Neff J, et al. Structural competency: curriculum for medical students, residents, and interprofessional teams on the structural factors that produce health disparities. (50)

- Summary of Resource: Using a structural competency framework, a training program detailing the impact of structural/systemic factors on health outcomes was provided to medical students and residents.

- Suggested Ideas for Implementation:

- Review the modules and incorporate them into trainee and faculty education.

- Below are several health equity education resources specific for emergency medicine. Also included are examples for how to implement educational content related to each resource.

Community Resource Links

Below are links to educational resources or supportive programs in the community that are working on this topic.

- Aysola, J and Myers, JS. Integrating Training in Quality Improvement and Health Equity in Graduate Medical Education: Two Curricula for the Price of One. (51)

- Summary of Resource: The article outlines a program developed to incorporate health equity and disparities into QI. Details of a 90-minute faculty development workshop are outlined.

- Suggested Ideas for Implementation:

- Using the faculty development workshop framework, hold a similar workshop at your institution.

- Encourage trainees and faculty to include health disparity reduction and health equity metrics in their current QI projects.

- Cross JJ, et. al. Neighbourhood walking tours for physicians-in-training. (52)

- Summary of Resource: Emergency medicine, internal medicine, and pediatric residents were taken on a neighborhood walking tour around the hospital. The goal of the walking tour was to introduce residents to community resources and organizations, while introducing concepts related to the social determinants of health. A pre-tour and post-tour survey showed the walking tour made residents more aware of the SDoH affecting their patients and community resources.

- Suggested Ideas for Implementation:

- Create a walking tour around your hospital or practice. During the tour, ask participants to identify the closest pharmacy, grocery store, social services organization, daycare center, bus or train station, and other resources near the hospital or practice. After the tour, debrief, allowing the participants to discuss pharmacy, food, and transit deserts, along with social service resource gaps. Take the learning a step further by asking participants how the knowledge they gained on the tour will affect their future practice, including which pharmacices and resources they refer to patients.

Video Links

Below are links to videos that do an excellent job of explaining or discussing this topic. Short clips could be used during a presentation to spark discussion, or links can be assigned as pre-work or sent out for further reflection after a presentation.

- Calardo SJ, et al. Realizing Inclusion and Systemic Equity in Medicine: Upstanding in the Medical Workplace (RISE UP)—an Antibias Curriculum (53)

- Summary of Resource: Realizing Inclusion and Systemic Equity in Medicine: Upstanding in the Medical Workplace (RISE UP), is an anti-bias, anti-racism communication curriculum composed of three hybrid (virtual and in-person) workshops.In The curriculum introduces tools for addressing bias, presents video simulations, and allows for small-group debriefings with guided role-play. It also reviews escalation pathways, reporting methods, and support systems. The curriculum includes a facilitator guide and pre-work.

- Suggested Ideas for Implementation:

- Offer a 60-minute virtual or in–person workshop session using this curriculum.

Simulation Scenario

Below are links to any simulation scenarios available on this topic area. Please credit the authors of the simulation if you use their work.

- Ward-Gaines J, et. al. Teaching emergency medicine residents health equity through simulation immersion. (54)

- Summary of Resource: Article outlines implementation of a large, case-based simulation project. Twenty emergency medicine residents, in groups of 2-3, participated in 8 case-based simulations that utilized standardized patients and patient mannequins of color to teach concepts related to DEI, such as gender bias, homlessness, mistrust in the medical system, etc.

- Suggested Ideas for Implementation:

- Using the case descriptions provided in the article new case-based simulations could be developed and implemented at your institution

- Incorporate health equity concepts into current case-based simulations at your program. For instance, a recent study found that women and racial/ethnic minority patients waited longer before being evaluated by a physician, had less EKGs performed, and were admitted less often than male and White patients, respectively, when presenting to the ED for chest pain. (46) If you are running a case simulation in which the patient’s chief complaint is chest pain, the patient could be female and/or a racial/ethnic minority. During the case debrief a discussion of gender and/or racial/ethnic bias and its impact on evaluation and treatment in the ED would be included.

- Vora S, et al. Recommendations and guidelines for the use of simulation to address structural racism and implicit bias. (7)

- Summary of Resource: This article provides guidelines to create simulation or role-play scenarios for learners to practice bias mitigation and antiracism skills.

- Suggested Ideas for Implementation:

- Use the article to create short role-play scenarios for learners to practice.

- Use Table 5 in the article as an opportunity to practice responses to microaggressions during DEI discussion or in general conversations.

Resources Summary Table

| Type of Educational Material | Educational Intervention Resource | Summary of Resource | Suggested Implementation |

| Case-based Simulations | Ward-Gaines J, et. al. Teaching emergency medicine residents health equity through simulation immersion. (54) | Article outlines implementation of a large, case-based simulation project. Twenty emergency medicine residents, in groups of 2-3, participated in 8 case-based simulations that utilized standardized patients and patient mannequins of color to teach concepts related to DEI, such as gender bias, homlessness, mistrust in the medical system, etc. |

|

| Video-based Simulation | Calardo SJ, et al. Realizing Inclusion and Systemic Equity in Medicine: Upstanding in the Medical Workplace (RISE UP)—an Antibias Curriculum (53) | Realizing Inclusion and Systemic Equity in Medicine: Upstanding in the Medical Workplace (RISE UP), is an antibias, anti-racism communication curriculum composed of three hybrid (virtual and in-person) workshops.In The curriculum introduces tools for addressing bias, presents video simulations, and allows for small-group debriefings with guided role-play. It also reviews escalation pathways, reporting methods, and support systems. The curriculum includes a facilitator guide and pre-work. | Have a 60-minute virtual or in–person workshop session using this curriculum. |

| Simulated-Participant based Simulation recommendations | Vora S, et al. Recommendations and guidelines for the use of simulation to address structural racism and implicit bias. (7) | This article provides guidelines to create simulation or role-play scenarios for learners to practice bias mitigation and antiracism skills. |

|

| Health Equity Coach Training | McMichael B, et al. The Impact of Health Equity Coaching on Patient's Perceptions of Cultural Competency and Communication in a Pediatric Emergency Department: An Intervention Design. (44) | The article discusses an intervention used to increase awareness of implicit bias and health disparities experienced by Indigenuous children and their families. | Using the outlined lecture content in the article, your program could develop similar educational lectures. Ideally, the education would be related to the patient populations most often served by your practice. Service learning opportunities aimed at community engagement could be developed for your practice. |

| Health Equity Journal Club | Smith KJ, et. al. Development of a health equity journal club to address health care disparities and improve cultural competence among emergency medicine practitioners. (45) | Article outlines the process of developing and implementing a journal club related to health equity at a large, academic-community emergency medicine residency program. |

|

| Health Equity & Quality Improvement (QI) Training | Aysola, J and Myers, JS. Integrating Training in Quality Improvement and Health Equity in Graduate Medical Education: Two Curricula for the Price of One. (51) | The article outlines a program developed to incorporate health equity and disparities into QI. Details of a 90-minute faculty development workshop are outlined. |

|

| Health Equity Resident-Led Retreat | Chary AN, et al. Addressing Racism in Medicine Through a Resident-Led Health Equity Retreat. (47) | A 3-hour retreat, held during mandatory residency didactic conference, in which residents participated in sessions about experiences of racism in the ED, microaggressions, and how physician bias affects the care of agitated patients. Preliminary data showed that “all participants reported improved understanding of diversity within the workplace and the majority found the retreat sessions to be helpful to their clinical practice”. |

|

| Implicit Bias Training | Zeidan AJ, et al. Implicit Bias Education and Emergency Medicine Training: Step One? Awareness.(48) | An educational intervention designed to increase residents’ awareness of their own implicit biases based on race was implemented. The intervention included a grand rounds lecture about implicit bias, time to take the Harvard Implicit Association Test (IAT) on race (49), and a 50 minute debrief discussion about results. The intervention had positive outcomes, with participants’ awareness of their own implicit biases increased by 33% and awareness of how their IAT scores influenced patient care by 9%. |

|

| Community walking tour | Cross JJ, et. al. Neighbourhood walking tours for physicians-in-training. (52) | Emergency medicine, internal medicine, and pediatric residents were taken on a neighborhood walking tour around the hospital. The goal of the walking tour was to introduce residents to community resources and organizations, while introducing concepts related to the social determinants of health. A pre-tour and post-tour survey showed the walking tour made residents more aware of the SDoH affecting their patients and community resources. | Create a walking tour around your hospital or practice. During the tour, ask participants to identify the closest pharmacy, grocery store, social services organization, daycare center, bus or train station, and other resources near the hospital or practice. After the tour, debrief; allowing the participants to discuss pharmacy, food, and transit deserts, along with social service resource gaps. Take the learning a step further by asking participants how the knowledge they gained on the tour will affect their future practice, including which pharmacices and resources they refer to patients. |

Quiz Questions/Answers

Possible questions and an answer key are provided below. These can be useful to document effectiveness in learning and knowledge gained but can also be useful to help learners identify that they may not actually know everything about a DEI topic, even if they have participated in presentations on it previously.

These discussion questions can be used with the “Related terms” section above to further discuss core terms related to DEI.

- Define health equity in your own words..

- What is the difference between equity and equality?

- True or False. Currently, the demographics of the US physician workforce matches the diversity of the US population?

Answer Key

- Health Equity: the opportunity for everyone in a society to achieve their “full health potential”

- Equity versus equality: Equality is providing the same to all. Equity recognizes differences in starting points and adjusts resource allocation to reach an equal outcome. Another way to explain is with equality everyone has the same and with equity everyone has what they need.

- False

Call to Action Prompt

Below is a statement that inspires participants to commit to meaningful action related to this topic in their own lives. This could be used to prompt reflection, discussion, or could be used in presentation closing.

Know the core definitions presented in this section so you can meaningfully participate in DEI work in your practice. As we work to dismantle inequitable systems, we must also consider what is in our control. As emergency physicians, we are often the gateway into the medical system. The care we provide can immensely change the course of a patient’s experience. Learn the evidence-based bias mitigation strategies and use them in your bedside practice. Learn the DEI term definitions and create spaces for open conversations on these uncomfortable topics

Reference

All references mentioned in the above sections are cited sequentially here.

- Start Here: A Primer on Diversity and Inclusion (Part 1 of 2) (harvardbusiness.org)

- https://icma.org/glossary-terms-race-equity-and-social-justice#K

- Equity vs. Equality. Marin County Office of Equity, 2020. <https://www.marinhhs.org/sites/default/files/boards/general/equality_v._equity_04_05_2021.pdf>

- Cross, T., Bazron, B. Dennis, K., & Isaacs, M. (1989). Towards a culturally competent system of care (Volume I). Washington, DC: Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development, CASSP Technical Assistance Center.

- Crenshaw, Kimberle () "Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics," University of Chicago Legal Forum: Vol. 1989: Iss. 1, Article 8. Available at: <http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8>

- Goode T. & Jones W. (modified 2009). National Center for Cultural Competence, Georgetown University Center for Child & Human Development. <https://nccc.georgetown.edu/foundations/framework.php#:~:text=Linguistic%20Competence%3A%20Definition&text=Linguistic%20competence%20requires%20organizational%20and,resources%20to%20support%20this%20capacity.>

- Brown, Italo M. MD, MPH. Diversity Matters: Blind Spots: EPs, Microaggressions, and Privilege. Emergency Medicine News: November 2020 - Volume 42 - Issue 11 - p 25 doi: 10.1097/01.EEM.0000722432.17104.45

- Vora S, Dahlen B, Adler M, Kessler DO, Jones VF, Kimble S, Calhoun A. Recommendations and guidelines for the use of simulation to address structural racism and implicit bias. Simulation in Healthcare. 2021 Aug 1;16(4):275-84.

- Ross JK, Aggarwal PC, Bessac F, Blacking J, Brentjes B, Casagrande LB, Casagrande JB, Cohen EN, Douglass WA, Gohring H, Gold GL. Social Borders: Definitions of Diversity [and Comments and Reply]. Current Anthropology. 1975 Mar 1;16(1):53-72.

- Hook JN, Davis DE, Owen J, Worthington EL, Utsey SO. Cultural humility: measuring openness to culturally diverse clients. J Couns Psychol. 2013 Jul;60(3):353-366. doi: 10.1037/a0032595. Epub 2013 May 6. Erratum in: J Couns Psychol. 2015 Jan;62(1):iii-v. PMID: 23647387.

- Hardeman RR, Medina EM, Kozhimannil KB. Structural racism and supporting Black lives—the role of health professionals. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016 Dec 1;375(22):2113-5.

- Heron SL, Lovell EO, Wang E, Bowman SH. Promoting diversity in emergency medicine: summary recommendations from the 2008 Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors (CORD) academic assembly diversity workgroup. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2009 May;16(5):450-3.

- Gomez LE, Bernet P. Diversity improves performance and outcomes. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2019 Aug 1;111(4):383-92.

- Landry A, Boatright D, Smith TY. Call to action in academic emergency medicine: Going beyond the appreciation of diversity, equity, and inclusion to true practice. AEM Educ Train. 2021 Sep 29;5(Suppl 1):S7-S9.

- Arno K, Davenport D, Shah M, Heinrich S, Gottlieb M. Addressing the Urgent Need for Racial Diversification in Emergency Medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2021 Jan;77(1):69-75. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.06.040. Epub 2020 Sep 30.

- Roberts, S. In a Generation, Minorities May Be the U.S. Majority. August 13, 2008.

- Cohen J, Gabriel B, Terrell C.The Case For Diversity In The Health Care Workforce. Health Affairs. 2002. Available at: https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.90. Accessed March 25, 2022.

- J.N. Laditka. Physician supply, physician diversity, and outcomes of primary health care for older persons in the United States. Health Place, 10 (3) (2004), pp. 231-244, 10.1016/j.healthplace.2003.09.00

- Aysola J, Clapp JT, Sullivan P, Brennan PJ, Higginbotham EJ, Kearney MD, Xu C, Thomas R, Griggs S, Abdirisak M, Hilton A, Omole T, Foster S, Mamtani M. Understanding Contributors to Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Emergency Department Throughput Times: a Sequential Mixed Methods Analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2022 Feb;37(2):341-350.

- Jetty A, Jabbarpour Y, Pollack J, Huerto R, Woo S, Petterson S. Patient-Physician Racial Concordance Associated with Improved Healthcare Use and Lower Healthcare Expenditures in Minority Populations. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022 Feb;9(1):68-81.

- Lau, ES. Hayes, SN, Volgman AS, et. al. Does Patient-Physician Gender Concordance Influence Patient Perceptions or Outcomes? Journal of the American College of Cardiology,Volume 77, Issue 8, 2021,Pages 1135-1138.

- Abreu, Carina, et al. "Characteristics of medical students interested in emergency medicine with intention to practice in underserved areas." AEM Education and Training 5 (2021): S65-S72.

- Saak, Julia C., et al. "Diversity begets diversity: factors contributing to emergency medicine residency gender diversity." AEM Education and Training 5 (2021): S73-S75.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Data Resource Book: Academic Year 2020-2021. Chicago, IL: ACGME; 2021. <ACGME Data Resource Book>

- Diversity in medicine: facts and figures 2019. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges, 2019. <https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/report/diversity-medicine-facts-and-figures-2019> (Accessed April 2, 2022).

- AAMC. Table B3. Number of Active Residents, by Type of Medical School, GME Specialty, and Sex. <https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/students-residents/interactive-data/report-residents/2021/table-b3-number-active-residents-type-medical-school-gme-specialty-and-sex> (Accessed April 2, 2022).

- AAMC. Table B5. Number of Active MD Residents, by Race/Ethnicity (Alone or in Combination) and GME Specialty. <https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/students-residents/interactive-data/report-residents/2021/table-b5-md-residents-race-ethnicity-and-specialty> (Accessed April 2, 2022).

- AAMC. Table B6. Number of Active DO Residents, by Race/Ethnicity (Alone or in Combination) and GME Specialty. <https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/students-residents/interactive-data/report-residents/2021/table-b6-do-residents-race-ethnicity-and-specialty> (Accessed April 2, 2022).

- Ehrhardt T, Shepherd A, Kinslow K, McKenney M, Elkbuli A. Diversity and inclusion among U.S. emergency medicine residency programs and practicing physicians: Towards equity in workforce. Am J Emerg Med 2021;46:690-2.

- Bureau, US Census. “Race and Ethnicity in the United States: 2010 Census and 2020 Census.” Census.gov, 9 June 2022, <https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/interactive/race-and-ethnicity-in-the-united-state-2010-and-2020-census.html>.

- Bureau, US Census. “Age and Sex in the United States: 2020 Census.” Census.gov, 9 June 2022, <Census Bureau Tables>.

- Beeson MS, Ankel F, Bhat R, Broder JS, Dimeo SP, Gorgas DL, Jones JS, Patel V, Schiller E, Ufberg JW; 2019 EM Model Review Task Force, Keehbauch JN; American Board of Emergency Medicine. The 2019 Model of the Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine. J Emerg Med. 2020 Jul;59(1):96-120. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.03.018. Epub 2020 May 29. PMID: 32475725.

- Mechanic OJ, Dubosh NM, Rosen CL, Landry AM. Cultural competency training in emergency medicine. J Emerg Med. 2017; 53(3): 391- 396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2017.04.019

- World Health Organization (WHO). Health Equity. <Health Equity -- Global (who.int)>.

- “What is Health Equity”. Episode 2, That’s Public Health Video Series. American Public Health Association (APHA). <What is Health Equity? Episode 2 of "That's Public Health" - YouTube>

- Hagiwara N, Kron FW, Scerbo MW, Watson GS: A call for grounding implicit bias training in clinical and translational frameworks. Lancet. 2020;395(10234):1457-1460.

- Narayan MC: Addressing Implicit Bias in Nursing: A Review. Am J Nurs. 2019;119(7).

- Holley, Lynn C., and Sue Steiner. “SAFE SPACE: STUDENT PERSPECTIVES ON CLASSROOM ENVIRONMENT.” Journal of Social Work Education, vol. 41, no. 1, 2005, pp. 49–64, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23044032. Accessed 18 Apr. 2022.

- FitzGerald C, Martin A, Berner D, Hurst S: Interventions designed to reduce implicit prejudices and implicit stereotypes in real world contexts: a systematic review. BMC Psychology. 2019;7(1):2

- DiAngelo, R. (2011). White Fragility. International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 3, 54-70.

- Ford CL, Airhihenbuwa CO. Critical Race Theory, race equity, and public health: toward antiracism praxis. Am J Public Health. 2010;100 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S30-S35.

- Salim, Rezaie. "Racial Bias with Pulse Oximetry?", REBEL EM blog, December 20, 2020. Available at: <https://rebelem.com/racial-bias-with-pulse-oximetry/>

- Sjoding MW, Dickson RP, Iwashyna TJ, Gay SE, Valley TS. Racial bias in pulse oximetry measurement. N Engl J Med2020;383:2477-8.

- Hoffman KM, Trawalter S, Axt JR, Oliver MN. Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016 Apr 19;113(16):4296-301.

- McMichael B, Nickel A, Duffy EA, Skjefte L, Lee L, Park P, Nelson SC, Puumala S, Kharbanda AB. The Impact of Health Equity Coaching on Patient's Perceptions of Cultural Competency and Communication in a Pediatric Emergency Department: An Intervention Design. J Patient Exp. 2019 Dec;6(4):257-264.

- Smith KJ, Harris EM, Albazzaz S, Carter MA. Development of a health equity journal club to address health care disparities and improve cultural competence among emergency medicine practitioners. AEM Educ Train. 2021 Sep 7;5(Suppl 1):S57-S64.

- Banco D, Chang J, Talmor N, Wadhera P, Mukhopadhyay A, Lu X, Dong S, Lu Y, Betensky RA, Blecker S, Safdar B, Reynolds HR. Sex and Race Differences in the Evaluation and Treatment of Young Adults Presenting to the Emergency Department With Chest Pain. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022 May 17;11(10):e024199.

- Chary AN, Molina MF, Dadabhoy FZ, Manchanda EC. Addressing Racism in Medicine Through a Resident-Led Health Equity Retreat. West J Emerg Med. 2020 Nov 20;22(1):41-44.

- Zeidan, AJ, UG Khatri, and J Aysola. “Implicit Bias Education and Emergency Medicine Training: Step One? Awareness.” AEM education and training. 3.1 (2018): 81–85.

- Project Implicit. <https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/takeatest.html>

- Neff J, Holmes SM, Knight KR, et al. Structural competency: curriculum for medical students, residents, and interprofessional teams on the structural factors that produce health disparities. MedEdPORTAL.2020;16:10888.

- Aysola, Jaya MD, MPH; Myers, Jennifer S. MD Integrating Training in Quality Improvement and Health Equity in Graduate Medical Education: Two Curricula for the Price of One, Academic Medicine: January 2018 - Volume 93 - Issue 1 - p 31-34.

- Cross JJ, Arora A, Howell B, Boatright D, Vijayakumar P, Cruz L, Smart J, Spell V, Greene A, Rosenthal M. Neighbourhood walking tours for physicians-in-training. Postgrad Med J. 2022 Feb;98(1156):79-85. Epub 2020 Dec 7.

- Calardo, Sarah J., et al. "Realizing Inclusion and Systemic Equity in Medicine: Upstanding in the Medical Workplace (RISE UP)—an Antibias Curriculum." MedEdPORTAL 18 (2022): 11233.

- Ward-Gaines J, Buchanan JA, Angerhofer C, McCormick T, Broadfoot KJ, Basha E, Blake J, Jones B, Sungar WG. Teaching emergency medicine residents health equity through simulation immersion. AEM Educ Train. 2021 Sep 29;5(Suppl 1):S102-S107.