Bias: Implicit vs Explicit, and Discrimination

Understanding Implicit Bias, Explicit Bias, Prejudice and Discrimination

Author: Emily Binstadt, MD MPH

Editor: Christine Stehman, MD

Definition(s) of Terms

Starting with a common understanding of key words, phrases, and potentially misunderstood related terms in DEI discussions helps ensure that all participants feel informed and welcome to participate in the discussion. Some terms have multiple definitions provided to help highlight nuances in the definitions.

Prejudice: “a preconceived, unfair judgment toward a person, group, or identity” (1) - pepperdine). Prejudice relates to feelings and attitudes that certain types of people are worth less or are less capable than others (2).

Stereotypes “are an exaggerated belief, image or distorted truth about a person or group—a generalization that allows for little or no individual differences. Stereotypes are based on images in mass media, or stories and perceptions about other groups passed on by parents, peers and other members of society. Stereotypes can be positive or negative” (3). A stereotype is a thought about a person or group of people, like a caricature, that exaggerates certain features while oversimplifying others, to make generalizations and judgements without personal knowledge of that individual or group. (2).

Discrimination “refers to behavior. It can be direct, indirect or structural and often results from stereotypes or prejudicial attitudes” (4). “Discrimination is unfair or prejudicial treatment of people and groups based on characteristics such as race, gender, age or sexual orientation”. (5)

Bias: “an inclination, tendency, or particular perspective toward something; can be favorable or unfavorable. When bias occurs outside of the perceiver’s awareness, it is classified as implicit bias” (1).

Types of Bias:

“Biases are preconceived notions based on beliefs, attitudes, and/or stereotypes about people pertaining to certain social categories that can be implicit or explicit. Because biases can be based on stereotypes rather than beliefs, an individual can hold a negative bias toward a group without believing that negative bias is true... Nevertheless, biases based on stereotypes rather than beliefs may still affect behavior. …While bias can lead to discriminatory behavior, it does not always. Notably, both individuals and institutions can be discriminatory” (6).

Affinity bias “is the unconscious tendency to show preference for those who are like us. This bias often shows up in the hiring process as we search for candidates that “fit” the culture of the department” (3).

Confirmation bias “occurs when we make a judgment or assumption about another person (these judgements and assumptions can be fueled by stereotypes), and we unconsciously look for evidence to back up our assumption of that person. We do this because we want to believe we’re right and that we’ve made the right assessment of a person” (3).

Synonyms/Related Terms

This section highlights the definitions of other words that may be used in discussion of this topic. Sometimes these words can be used interchangeably with the terms defined above, and sometimes they may have been used interchangeably historically, but have distinct meanings in DEI conversations that it is helpful to recognize.

Blatant biases “(also called explicit biases) are conscious beliefs, feelings, and behavior that people are perfectly willing to admit, which express hostility toward other groups (outgroups) while unduly favoring one’s own group (in-group). Classic examples of blatant bias include the views of members of hate groups such as the Ku Klux Klan and members of Hitler’s Nazi party” (2).

Subtle biases “(also called automatic or implicit biases) are unexamined and sometimes unconscious, but just as real in their consequences. They are automatic, ambiguous, and ambivalent, but nonetheless biased, unfair, and disrespectful to a belief in equality. They can be measured by the Implicit Association Test People’s reaction time on the IAT predicts actual feelings about out-group members, decisions about them, and behavior toward them, especially nonverbal behavior (2).

Racial anxiety: discomfort and awkwardness around people in a different racial group, which can be improved with increased contact with that racial group.

Stereotype threat: the concern that your performance will be perceived as confirming a stereotype. This concern can then distract and detract from the actual performance, potentially confirming the stereotype. An example is a white teacher offering less specific, actionable feedback to black students out of fear of being labeled racist; yet, ultimately providing a less robust education to black students (which is indeed racist).

Scaling This Resource: Recommended Use

As many users may have varying amounts of time to present this material, the authors have recommended which resources they would use with different timeframes for the presentation.

1 minute: Present basic definitions of terms for implicit bias and discrimination, and introduce IAT and provide a link to a test. Encourage participants to take an IAT test. Ideally, you would also introduce the tools that can be used to mitigate implicit bias, but this will likely require 5 minutes at a minimum

10 minute: Same as above, but include additional definitions of stereotypes and prejudice. Add a discussion of the tools to mitigate implicit bias, both for individuals and institutions, and time for participants to reflect on call to action.

30 minutes: Same as above, but include additional definitions of affinity bias and confirmation bias. Consider adding discussion questions. Consider doing “circle of trust” activity in community resources. From barriers/challenges/controversies: recommend reading the facilitator's guide and consider introducing the topic with some mutually agreed-upon ground rules.

Discussion/Background

This section provides an overview of this topic so that an educator who is not deeply familiar with it can understand the basic concepts in enough detail to introduce and facilitate a discussion on the topic. This introduction covers the importance of this topic as well as relevant historical background.

When used in DEI discussions, words like prejudice, bias, and discrimination have an implied “against” after them. They have negative connotations and usually involve negative attitudes towards a group of people. There are key differences between these terms, however. Bias includes both prejudices (based on emotions and feelings) and stereotypes (based on cognitive beliefs). Bias refers to beliefs and judgements and discrimination refers to behaviors. Discrimination is bias in action (7).

Prejudice only exists inside a person’s head. Discrimination is how they apply their prejudice to a group of people. Being prejudiced is not a crime, but acting on it by discriminating against a [member or members of a] class of people is illegal (8).

Most people and organizations in medicine would like to think of themselves as open-minded, accepting, and fair. Unfortunately, we all have lived experiences that result in biases, many of which may be unconscious or implicit. To prevent these biases from resulting in discriminatory decision-making and actions, we need to be able to recognize them and to use tools to reduce or prevent their influence on our behavior as individuals and as systems.

Why do I have prejudices?

We all have identities which link us to certain gender, race, socio-economic, religious, political, and other groups. Humans tend to hold higher esteem for those in their shared identity groups (in-group) and may exaggerate the differences between themselves and those who do not share those identities (out-group). This may have been evolutionarily beneficial, by aligning us into smaller groups of people who banded together for mutual protection, but now it can result in a tendency to form strong but inaccurate opinions and emotions towards individuals in either our in-group or out-group (prejudices). Since the 1970s, researchers have explored this human tendency, calling it Social Identity Theory (9). People may have different levels of comfort with ambiguity, and those with less comfort may revert to quick categorization as a way of feeling a sense of more control and less ambiguity in their lives. Our subconscious brains may be more adapted to quickly categorizing people than our conscious, rational selves would like to accept. Even people who confidently affirm a strong belief in equal treatment towards individuals of all different races, genders, religions and other group designations may show unconscious preferences toward a certain group, or may have unconscious beliefs about members of that group’s capabilities. We can measure some of these beliefs and preferences through Implicit Association Tests (IAT). The implicit biases measured by IATs regarding race correlate more closely with behaviors than do any conscious, stated beliefs about race. (10) In addition to implicit biases, factors such as racial anxiety (awkwardness around people not in your in-group) and stereotype threat (concern that your performance will be perceived as confirming a stereotype) can also contribute to behaviors that result in discrimination.

What is wrong with using stereotypes?

We use heuristic tools like stereotypes to help us make quick decisions, but decisions made using stereotyped beliefs do not account for any individual differences in personality, intention, or achievement. Thus, these quick decisions relying on stereotypes can result in discriminatory action. Any force that promotes pressured decision-making in hiring, promotion, or assessment situations will increase the likelihood of reverting to using stereotypes, and thus increases the likelihood for discrimination.

Why should I identify my implicit biases if I can’t control them?

Improving our individual and institutional capabilities to identify and to mitigate our implicit biases so that they do not result in discrimination is the goal for the future. Specific strategies which have shown promise in this area are discussed in detail under the “Opportunities” heading.

Individuals can practice 1) imagining a non-stereotyped response whenever a use of stereotype is identified, 2) identifying counter-stereotype individuals or situations, 3) focusing on individual characteristics of people in a stereotyped group, 4) imagining being in the shoes of an individual in a stereotyped group, and 5) increasing contact with people in that group.

Institutions can 1) help increase awareness of implicit bias, 2) promote shared values focusing on the importance of fairness rather than threatening punishment for injustice, 3) insist on systems which promote mindful deliberate thinking to diminish the default use of implicit biases, especially in all hiring and promotion and award-selection settings, and 4) take measurements of any areas where biased results might be found and publicize them, discuss them and address them.

Quantitative Analysis/Statistics of note

This section highlights the objective data available for this topic, which can be helpful to include to balance qualitative or persuasive analysis or to help define a starting point for discussion.

The statistics below are a sampling of data showing that discrimination negatively affects the emergency physician workforce at all levels of training and career advancement, as well as the patients for whom they provide care.

- Of 7680 surveyed EM residents, “3463 (45.1%) reported exposure to some type of workplace mistreatment (eg, discrimination, abuse, or harassment) during the most recent academic year. A frequent source of mistreatment was identified as patients and/or patients’ families” (11).

- EM faculty from racial and gender minority groups reported higher rates of discrimination at work. 48% of non-White EM faculty reported discriminatory treatment compared to 12.6% of White EM faculty (CI for difference, 16.6% – 54.2%). Both groups were equally likely to report having observed race-based discrimination of another physician. EM faculty who identified as sexual minorities reported higher overt gender discrimination at work scores than their heterosexual colleagues (12).

- 62.7% of female EM faculty and 12.5% of male EM faculty reported gender-based discriminatory treatment at work, although male and female faculty were equally likely to report having observed gender-based discriminatory treatment of another physician. The three most frequent sources of experienced or observed gender-based discriminatory treatment were patients, consulting or admitting physicians, and nursing staff (12).

- “Forty percent of respondents ranked gender discrimination first out of 11 possible choices for hindering their career in academic medicine. Thirty-five percent ranked gender discrimination second to either "limited time for professional work" or "lack of mentoring." Respondents rated themselves as poorly prepared to deal with gender discrimination and noted effects on professional self-confidence, self-esteem, collegiality, isolation, and career satisfaction. The hierarchical structure in academe is perceived to work against women, as there are few women at the top. Women faculty who have experienced gender discrimination perceive that little can be done to directly address this issue. Institutions need to be proactive and recurrently evaluate the gender climate, as well as provide transparent information and fair scrutiny of promotion and salary decisions” (13).

- Racial Dynamics in Health Care (10)

- Physicians were 40% less likely to refer African Americans for cardiac catheterization than whites; the lowest referral rates were for African American women.

- Doctors’ levels of bias largely mirrored those of the general population, with medical doctors strongly preferring whites over blacks. Doctors in some fields, such as pediatrics, showed less biased behavioral responses to racial differences.

- Physicians engaged with patients of color may be less likely to be empathic, to elicit sufficient information, and to encourage patients to participate in medical decision-making.

- African American patients have a greater level of distrust toward white counselors in clinical settings, which has serious consequences for mental health care, as well as physical health care.

- Physicians were 40% less likely to refer African Americans for cardiac catheterization than whites; the lowest referral rates were for African American women.

- 35 out of 42 reviewed articles found evidence of implicit bias in healthcare professionals; all the studies that investigated correlations found a significant positive relationship between level of implicit bias and lower quality of care (15).

Slide Presentation or Images

Images and graphical representations in presentations can clarify concepts and enhance interest. Please cite the sources of these images appropriately if you use them in your presentation, found in the last section of this page. We purposefully avoided providing complete slide decks in this curriculum, and instead opted to offer easy building blocks for a great personalized presentation regardless of the format.

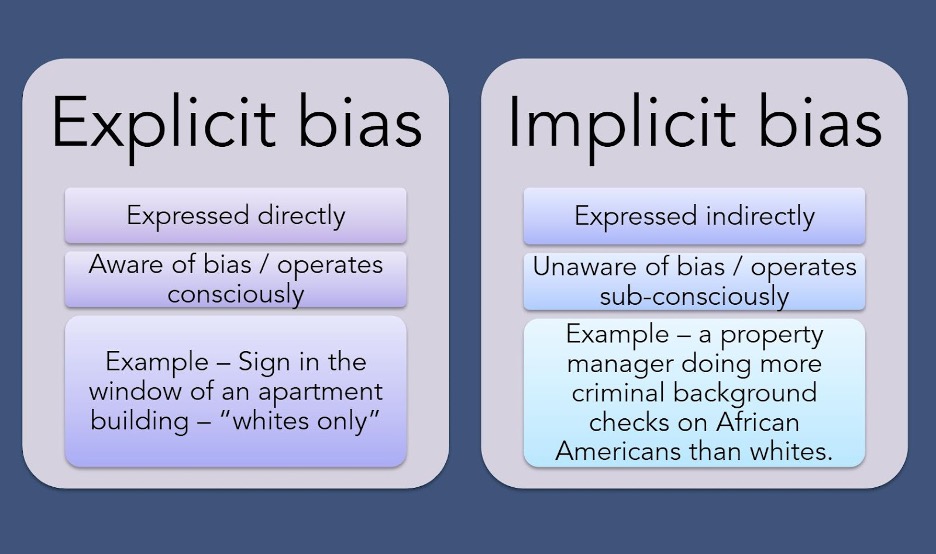

Could use this as a prompt to explain explicit vs implicit bias and to prompt brainstorming of examples of explicit and implicit bias in medicine instead of housing (15).

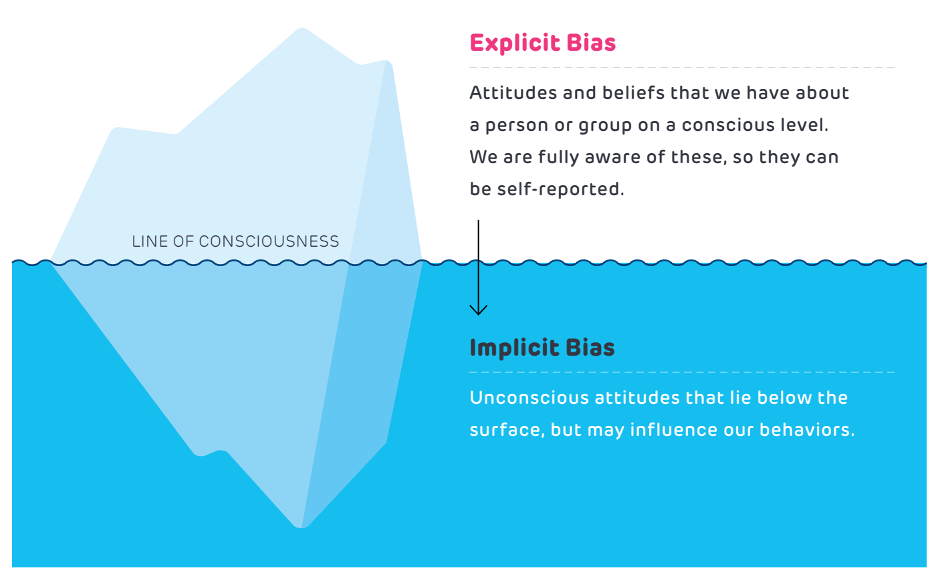

This slide illustrates visually that implicit bias can still have significant influence, even if it is not overtly recognized (17)

The graphic below, by Kim Scott, author of the book “Just Work”, helps summarize the differences between Bias, Prejudice and Bullying, and suggests strategies to deal with each. An example of an “I” statement is: “I don’t think you meant that the way it sounded.” An “it” statement is: “It is illegal to…”, and a “you” statement is: “You can’t talk to me that way.” (Here, Bias is actually referring to implicit bias.)

From: 8 questions with Kim Scott About Bias, Prejudice, Bullying and Just Work. The Blog: Radical Reading by Kim Scott and Trier Bryant.

Role-playing Scenario

Role-playing scenarios can enhance investment and participation. Always consider psychological safety when asking participants to engage in any role-playing activity to avoid potential adverse effects. We highly recommend a discussion for each group to agree on ground rules of respectful learning prior to engaging in any role-playing scenarios (embrace ambiguity, commit to learning together, listen actively, create a brave space, suspend judgment, etc.). It is reasonable to review these ground rules prior to each role-playing discussion.

Some evidence exists that imagining positive interactions with an individual belonging to a group against which you hold implicit bias can help reduce that bias.

- Can you identify a group against which you hold implicit bias (perhaps identified by IAT score)?

- Imagine yourself in a situation with an individual from that group doing a shared activity which you love (sports, music, nature etc) and in the process, learning something about that individual’s life which is similar to or has resonance with something in your life (18).

Barriers/Challenges/Controversies

This section should help the facilitator anticipate any questions, naysayers, rebuttals, or other feedback they may encounter when presenting the topic and allow preparation with thoughtful responses. Facilitators may experience concerns about their personal ability to present a specific DEI topic (ie a white facilitator presenting on anti-racism or minority tax), and this section may address some of those tensions.

When initiating conversations about discrimination and implicit bias, be aware of a few common stumbling blocks:

- Participants expressing concerns about the validity of the IAT or other means of measuring implicit bias or other measures of discrimination.

- Silence and non-participation because the discussion of discrimination and bias is uncomfortable, and people don’t want to trigger others, show their own vulnerabilities or lack of knowledge, and may be concerned about “stereotype threat” (being perceived as having the stereotypical viewpoints/beliefs or traits of those in the groups with which they identify).

- Allowing discussion of the ubiquitousness of implicit bias to justify it or normalize it, such that participants do not feel compelled to take action to mitigate these biases.

This last barrier is important to consider in every presentation because unless one states clearly that “although we all have implicit bias, this does not make it justified”, the educational effort could potentially have more negative than positive impact.

Brown University has published a guide for facilitators of discussions on Implicit Bias, including discussion question prompts that can be used to move conversation along if it gets stuck on points 1 or 2 above. Additionally, they recommend setting some ground rules for discussion prior to beginning, which can help avoid these issues. These rules are listed below, and the full handbook can be accessed here (3).

Suggested Communication Agreements:

- We will speak for ourselves and allow others to speak for themselves, with no pressure to represent or explain a whole group.

- We will listen with resilience, “hanging in” when something is hard to hear (see message about discomfort below).

- If tempted to make attributions about the beliefs of others (e.g., “You just believe that because…”), we will instead ask a question to check out the assumption we are making (e.g., “Do you believe that because…?” or, “What leads you to that belief?”).

- We will share airtime and participate within the suggested timeframes.

- We will not interrupt except to indicate that we cannot or did not hear a speaker.

- We will assume good intentions without ignoring impact.

- We will keep in mind that understanding and agreeing are not the same thing.

- What is shared here stays here; what’s learned can leave.

A Message about Discomfort:

Conversations about diversity often require us to be vulnerable which can make people feel uncomfortable. As a leader, encouraging vulnerability and inviting your audience to sit in/with their discomfort can make learning more personal and productive (3).

Managing Naysayers:

Be prepared for those who may try to derail the conversation. They can negatively impact others’ learning experiences and potentially cause harm by invalidating the experiences of marginalized participants. Consider highlighting communication agreements 2 and 7, acknowledging the naysayers’ comments and then asking for other perspectives from the rest of the group to move the conversation forward (3).Ethical Issues

This section may be useful to hospital ethics committees who want to increase their DEI awareness as part of monthly meetings, or to other groups who are interested in the ethical underpinnings of the topic.

A wide variety of ethical theories focus on these issues: virtue-based, rights-based, deontological, etc. Section 2 of this booklet gives a lot of discussion of the philosophical basis of what makes discrimination wrong (19).

Unconscious bias and discrimination directly impact issues of justice

Researchers have shown that stereotyping and associated responses are automatic and unconscious. A particularly disturbing example involves a series of experiments in which participants played a video game. During the game, an individual who was sometimes White and sometimes Black appeared spontaneously, carrying either a gun or a different, non-threatening object. The participants were told to ‘shoot’ when the intruder was carrying a gun, but to press another key if the intruder was carrying a benign object. The results showed that the number of times the participants accidentally perceived the object to be a gun was much higher when the intruder was Black than when the intruder was White. The results were similar for White and Black participants, indicating that negative stereotypes can exist intragroup as well as intergroup (20).Opportunities

Sometimes DEI topics can present depressing history and statistics. This section highlights glimmers of hope for the future: exciting projects, areas of study inspired by the topic, or even ironic twists where progress has emerged or may be anticipated in the future.

Some have derided implicit bias training sessions as not effective in reducing implicit bias or discriminatory behavior and potentially worsening these by normalizing implicit biases (21). Effective interventions require a longer-term commitment than a single awareness-raising session to result in meaningful change. Two specific examples are detailed below:

1) According to Deveine et al, (22) there are ways that you can reduce your implicit biases. The authors of this paper used a multi-faceted approach involving the five strategies outlined below over 12 weeks to produce long-term reductions in implicit race bias, increased awareness of bias, and concern about discrimination

- Stereotype replacement: Replacing stereotypical responses with non-stereotypical responses involves recognizing and labeling the response as stereotypical, reflecting on why it occurred and how it could be avoided in the future, then brainstorming and selecting an alternate unbiased response.

- Counter-stereotypic imaging: Imagining detailed counter-stereotypic examples, either abstract (e.g., smart Black people), famous (e.g., Barack Obama), or non-famous (e.g., a personal friend) helps challenge stereotypes by making counter-stereotypical examples more accessible.

- Individuation: Obtaining specific personal information about group members and using it for evaluations reduces the influence of stereotypical inferences based on group attributes.

- Perspective taking: Seeking out first-person perspectives of a member of a stereotyped group improves psychological closeness to that group and reduces automatic group-based assessments.

- Increasing opportunities for contact: Increased contact with stigmatized groups allows more opportunities to engage in positive interactions with out-group members which can change the underlying automatic beliefs, understandings or assessments of the group.

2) Jerry Kang and a group of researchers developed the following list of interventions that have been found to be constructive for institutions which would like to strive to reduce bias (23). Although many of these could also refer to individual beliefs/values, institutions with policies which systematically prioritized these values were more effective in identifying and reducing bias.

- Doubt objectivity: Presuming oneself to be objective actually tends to increase the role of implicit bias; teaching people about non-conscious thought processes will lead people to be skeptical of their own objectivity and better able to guard against biased evaluations.

- Increase motivation to be fair: Promoting employees’ internal motivations toward fairness, rather than developing a punitive environment with fear of external judgments, tends to decrease biased actions.

- Improve conditions of decision-making: Implicit biases are a function of automaticity (what Daniel Kahneman refers to as “thinking fast”). “Thinking slow” by engaging in mindful, deliberate processing prevents our implicit biases from kicking in and determining our behaviors.

- Count: Implicitly biased behavior is best detected by using data to determine whether patterns of behavior are leading to disparate outcomes. Once one is aware that decisions or behavior are having disparate outcomes, it is then possible to consider whether the outcomes are linked to bias (10).

Narayan offers a summary table of the literature recommending various techniques to overcome implicit bias (24).

Journal Club Article links

A journal club facilitator can access several salient publications on this topic below. Alternatively, an article can be distributed ahead of a presentation to prompt discussion or to provide a common background of understanding. Descriptions and links to articles are provided.

- Michelle D. Lall, MD, MHS; Karl Y. Bilimoria, MD, MS; Dave W. Lu, MD, MSCI, MBE; Tiannan Zhan, MS; Melissa A. Barton, MD; Yue-Yung Hu, MD, MPH; Michael S. Beeson, MD, MBA; James G. Adams, MD; Lewis S. Nelson, MD;

Jill M. Baren, MD, MBA. Prevalence of Discrimination, Abuse, and Harassment in Emergency

Medicine Residency Training in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(8):e2121706.

- This article describes results of a survey of discrimination prevalence among Emergency Medicine residents (11). It could offer discussion of whether these findings are expected or surprising, and whether that is different for different readers.

- Link: Prevalence of Discrimination, Abuse, and Harassment in Emergency Medicine Residency Training in the US | Emergency Medicine | JAMA Network Open | JAMA Network

- Devine PG, Forscher PS, Austin AJ, Cox WT. Long-term reduction in implicit race bias: A prejudice habit-breaking intervention. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2012;48(6):1267-1278.

- Discusses a randomized controlled trial in which grad students were able to decrease their implicit biases using 5 different techniques over 12 weeks (22). A closer reading of effective techniques, with associated examples, may be helpful for learners at all levels of training to understand tactics they could use to reduce their own unwanted biases.

- Link: Long-term reduction in implicit race bias: A prejudice habit-breaking intervention - PMC

- Mateo, Camila M. MD, MPH; Williams, David R. PhD, MPH More Than Words: A Vision to Address Bias and Reduce Discrimination in the Health Professions Learning Environment, Academic Medicine: December 2020 - Volume 95 - Issue 12S - p S169-S177

- Focuses on examples that medical institutions can use to decrease bias and discrimination. May prompt discussion for specific ideas for own-institution progress (6).

- Link: More Than Words: A Vision to Address Bias and Reduce Discrimination in the Health Professions Learning Environment

- Chandrashekar, Pooja; Jain, Sachin H. MD, MBA Addressing Patient Bias and Discrimination Against Clinicians of Diverse Backgrounds, Academic Medicine: December 2020 - Volume 95 - Issue 12S - p S33-S43

- The authors discuss the ethical dilemmas associated with responding to prejudiced patients and then present a framework for clinicians to use as well as institution-level strategies to address patient bias (25).

- Link: Addressing Patient Bias and Discrimination Against Clinicians of Diverse Backgrounds

- Stone, J., Moskowitz, G. B., Zestcott, C. A., & Wolsiefer, K. J. (2020). Testing active learning workshops for reducing implicit stereotyping of Hispanics by majority and minority group medical students. Stigma and Health, 5(1), 94–103.

- An intervention among medical students to reduce implicit bias was successful among most identity groups, but not all (26). Readers could discuss potential explanations for why these differences occurred.

- Link: https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000179

Discussion Questions

The questions below could start a meaningful discussion in a group of EM physicians on this topic. Consider brainstorming follow-up questions as well.

- Do you know more people from different kinds of social groups than your parents did? How often do you hear people criticizing groups without knowing anything about them? Take the IAT. Could you feel that some associations are easier than others? Do you or someone you know believe that group hierarchies are inevitable? Desirable?

- Is it comfortable to talk about your implicit biases? If we can’t talk about them, how can we address them? If you had a conversation about racism with someone who stated “I don’t see color”, does this allow continuation of the conversation? How could you address this situation?

- What are some concrete ways that you can change the systems in your organization/department/hospital so that potential implicit biases are recognized prior to making important decisions, and pressures to use stereotyped or prejudiced beliefs are minimized?

Summary/Take-home Themes

The authors summarize their key points for this topic below. This could be useful to create a presentation closing.

- We all have implicit bias, but that doesn’t mean they are OK. Since implicit biases can predict discriminatory behavior, even in a person who consciously disavows such behavior, we have a responsibility to identify these biases and mitigate them and interrupt their ultimate effect on our actions.

- We can work as individuals and institutions to monitor for the existence of implicit biases by proactively collecting demographic data and purposefully looking for any evidence of bias.

- Individuals and institutions can mitigate the effects of implicit biases only with ongoing dedication to identifying, discussing and addressing them. Tools to combat bias must be recognized, valued, prioritized and woven into daily activities and every important decision to be effective in neutralizing bias.

Relevant Quotations

Meaningful and relevant quotations (appropriately attributed) can be used to enhance presentations on this topic.

“We cannot unlearn what we are too afraid to acknowledge. If you’re not uncomfortable while talking about diversity and inclusion, then I assure you, you’re not doing it right.” - Michelle Kim (3)

Specialty Resource Links

Below are links to Emergency Medicine-specific resources for this topic.

MN Doctors for Health Equity has this one-page Implicit Bias Primer with graphics that provides an introduction to concepts and links to relevant high-quality information.

Community Resource Links

Below are links to educational resources or supportive programs in the community that are working on this topic.

- Understanding Prejudice.org: Exercises and Demonstrations - non-medical thought-provoking surveys and activities that could be completed and then used to prompt discussion

- The Circle of Trust Activity to help participants identify unconscious affinity bias

- 3 ½ Minutes, Ten Bullets is a critically acclaimed 2015 documentary film regarding the murder of Jordan Davis, an African-American teenager who was shot by Michael Dunn on November 23, 2012, at a gas station in Jacksonville, Florida. A discussion guide by Perception Institute, Participant Media is available here, to help discuss the perspectives of the characters in this film, and the implications for societal issues of discrimination and bias. 3 ½ Minutes, Ten Bullets - Discussion Guide

Video Links

Below are links to videos that do an excellent job of explaining or discussing this topic. Short clips could be used during a presentation to spark discussion, or links can be assigned as pre-work or sent out for further reflection after a presentation.

Videos of lectures on implicit bias, each approximately one hour long which could be used as required viewing prior to a session on implicit bias.

Implicit Bias | racism-on-the-table

Putting Racism on the Table: Breaking the Prejudice Habit Videos and discussion prompts on implicit bias and racism.

On the other end of the spectrum, approximately two min video introducing implicit bias. This video does not address how to mitigate bias; it only focuses on the ubiquity and normalcy of having implicit biases. Implicit Bias: Peanut Butter, Jelly and Racism | PBSSimulation Scenarios

Below are links to any simulation scenarios available on this topic area. Please credit the authors of the simulation if you use their work.

Vora et al (27) describe methods to discuss racism and implicit bias using simulation. Recommendations and Guidelines for the Use of Simulation to Address Structural Racism and Implicit Bias

Tool to use to avoid the discriminatory use of simulation Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion in Simulation – A Reflexive Tool for Simulation Delivery Teams – ICE Blog

Specific simulation scenarios to address implicit bias and stereotypes: These scenarios require a subscription to access in full, but summaries are also available on the website which might serve as good prompts for local scenario development.

Quiz Questions/Answers

Possible questions and an answer key are provided below. These can be useful to document effectiveness in learning and knowledge gained but can also be useful to help learners identify that they may not actually know everything about a DEI topic, even if they have participated in presentations on it previously.

- Even though they may not be aware of them, everyone carries implicit biases based on their upbringing and environmental and social cues in their lives. While you can learn about these biases through implicit association tests (IAT), they will always be with you and are impossible to change. (T/F)

- Institutions can address systemic bias by:

- Keeping track of demographic data and routinely discussing them to see if any evidence for disparities exists.

- Encourage slow, deliberate thinking rather than quick “gut reaction” thinking to minimize use of stereotypes in all important hiring, promotion and award decisions.

- Teach employees about the existence of implicit biases so they will be open to doubting their own objectivity in situations where bias may be present.

- All of the above

- What are some strategies that individuals can use to mitigate their implicit biases?

- Recognizing examples of stereotypical behaviors.

- Imagining examples which run counter to common stereotypes.

- Noting commonalities among groups of people.

- Reflecting on how you could have performed better than someone in another group of people.

- Avoiding adding to stereotyped interactions by avoiding contact with people that are often stereotyped.

Answer Key

- FALSE

Although everyone likely has some implicit biases, and these can be identified on IATs, implicit biases can be changed with ongoing work and dedication (22). - D, All of the Above

These are all ways that institutions can combat bias. Additionally, they can promote the institutional value of fairness, but not with a system that focuses primarily on punishment for unfairness when discovered (23). - B

All of the other statements are actually opposite of the recommended behaviors, which include A) Stereotype replacement: Thinking of non-stereotypical examples of behaviors or images to substitute whenever stereotypical ones are noted. C) Individuation: noticing the individual characteristics of people. D) Perspective Taking: imagine yourself in the shoes of another person, using their perspective. E) Increase Contact: when you spend more time with others in groups with whom you do not share common identity, you increase opportunities to do all of the above tasks and form positive bonds (22).

Call to Action Prompt

Below is a statement that inspires participants to commit to meaningful action related to this topic in their own lives. This could be used to prompt reflection, discussion, or could be used in a presentation closing.

While everyone has implicit biases, we can strive to identify them and mitigate the chance that these will influence our behavior and cause us to participate in discrimination. To be effective, these mitigation efforts and tools have to be used routinely. Can you commit to something that you can do on an ongoing basis that will help address your implicit biases? (Activity: Brainstorm ideas of ways to use the implicit bias mitigation tools outlined here to make changes in the way you run meetings, interact with patients, watch TV with your children, solicit or give feedback, or anything else that is a personal commitment for you). Make an appointment on your calendar in one month to reflect on how well you’ve met this goal, and whether you are ready to add an additional goal. Repeat!

Reference

All references mentioned in the above sections are cited sequentially here.

- Confronting Prejudice: how to protect yourself and help others. the Online Master of Psychology program from Pepperdine University. July 9, 2019. Accessed here:https://onlinegrad.pepperdine.edu/blog/prejudice-discrimination-coping-skills/

- Fiske, S. T. (2022). Prejudice, discrimination, and stereotyping. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/jfkx7nrd

- Understanding the impact of unconscious bias in a university setting: A module for faculty and staff at Brown. Discussion Guide. Accessed here: https://www.brown.edu/about/administration/institutional-diversity/sites/oidi/files/Unconscious%20Bias%20Discussion%20Guide.pdf

- Resources on Stereotypes and Discrimination. The Cayman Islands Ministry of Education, Employment and Gender Affairs, the Gender Affairs Unit. Accessed here: http://genderequality.gov.ky/resources/stereotypes-and-prejudice

- Discrimination: What it is, and Howhow to cope. American Psychological Association. October 31, 2019. Accessed here: https://www.apa.org/topics/racism-bias-discrimination/types-stress

- Mateo, Camila M. MD, MPH; Williams, David R. PhD, MPH More Than Words: A Vision to Address Bias and Reduce Discrimination in the Health Professions Learning Environment, Academic Medicine: December 2020 - Volume 95 - Issue 12S - p S169-S177 doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003684

- Learning for Justice. Classroom Resource: Exploring bias and discrimination in hiring practices. Accessed here: https://www.learningforjustice.org/classroom-resources/lessons/exploring-bias-and-discrimination-in-hiring-practices#:~:text=bias%20%5B%20b%C4%AB%C9%99s%20%5D%20(verb),Discrimination%20is%20prejudice%20in%20action.

- grammar/your dictionary.com. Accessed here: https://grammar.yourdictionary.com/vs/difference-between-prejudice-and-discrimination-defined.html

- Taijfel, H. (1970). "Experiments in intergroup discrimination" (PDF). Scientific American. 223 (5): 96–102. Bibcode:1970SciAm.223e..96T. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1170-96. JSTOR 24927662. PMID 5482577. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-12-06.

- Godsil, R. D., Tropp, L. R., Goff, P. A. & powell, j.a., (2014). The Science of Equality (Volume 1): Implicit Bias, Racial Anxiety and Stereotype Threat. https://equity.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Science-of-Equality-Vol.-1-Perception-Institute-2014.pdf

- Michelle D. Lall, MD, MHS; Karl Y. Bilimoria, MD, MS; Dave W. Lu, MD, MSCI, MBE; Tiannan Zhan, MS; Melissa A. Barton, MD; Yue-Yung Hu, MD, MPH; Michael S. Beeson, MD, MBA; James G. Adams, MD; Lewis S. Nelson, MD; Jill M. Baren, MD, MBA. Prevalence of Discrimination, Abuse, and Harassment in Emergency Medicine Residency Training in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(8):e2121706. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.21706. Accessed here: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/article-abstract/2783236

- Lu DW, Pierce A, Jauregui J, et al. Academic Emergency Medicine Faculty Experiences with Racial and Sexual Orientation Discrimination. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(5):1160-1169. Published 2020 Aug 21. doi:10.5811/westjem.2020.6.47123

- Lu DW, Lall MD, Mitzman J, et al. #MeToo in EM: A Multicenter Survey of Academic Emergency Medicine Faculty on Their Experiences with Gender Discrimination and Sexual Harassment. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(2):252-260. Published 2020 Feb 21. doi:10.5811/westjem.2019.11.44592

- Phyllis L. Carr, Laura Szalacha, Rosalind Barnett, Cheryl Caswell, and Thomas Inui.Journal of Women's Health.Dec 2003.1009-1018. http://doi.org/10.1089/154099903322643938

- FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics. 2017;18(1):19. Published 2017 Mar 1. doi:10.1186/s12910-017-0179-8

- Tweeted by The Non-Profit Housing Association of Northern California. Accessed here: https://twitter.com/NPHANC/status/1175115991614775296

- Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Policy Lab. Understanding Physician Implicit Racial Bias. Image accessed here: https://policylab.chop.edu/understanding-physician-implicit-racial-bias

- Crisp, R. J., & Turner, R. N. (2009). Can imagined interactions produce positive perceptions?: Reducing prejudice through simulated social contact. American Psychologist, 64(4), 231–240. Accessed here: https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014718

- Kasper Lippert-Rasmussen. The Routledge Handbook of the Ethics of Discrimination. Aug 21, 2017. Accessed here: https://www.routledge.com/The-Routledge-Handbook-of-the-Ethics-of-Discrimination/Lippert-Rasmussen/p/book/9781138928749

- Correll J, Urland GR, Ito TA. Event-related potentials and the decision to shoot: The role of threat perception and cognitive control. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 42 (2006) 120–128. Accessed here: http://psych.colorado.edu/~jclab/pdfs/Correll,%20Urland%20&%20Ito%20(2006).pdf

- Gino F, Coffman C. Unconscious bias training that works. Harvard Business Review August-September 2021. Accessed here: https://hbr.org/2021/09/unconscious-bias-training-that-works

- Devine PG, Forscher PS, Austin AJ, Cox WT. Long-term reduction in implicit race bias: A prejudice habit-breaking intervention. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2012;48(6):1267-1278. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2012.06.003 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3603687/

- Kang, J., Bennett, M., Carbado, D., Casey, P., Dasgupta, N., Faigman, D., Godsil, R. D., Greenwald, A. G., Levinson, J. D., Mnookin, J. (2012). Implicit bias in the courtroom. UCLA Law Review, 59(5), 1124-1186.

- Narayan MC. CE: Addressing Implicit Bias in Nursing: A Review. Am J Nurs. 2019 Jul;119(7):36-43. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000569340.27659.5a. PMID: 31180913.

- Chandrashekar, Pooja; Jain, Sachin H. MD, MBA Addressing Patient Bias and Discrimination Against Clinicians of Diverse Backgrounds, Academic Medicine: December 2020 - Volume 95 - Issue 12S - p S33-S43

- doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003682

- Stone, J., Moskowitz, G. B., Zestcott, C. A., & Wolsiefer, K. J. (2020). Testing active learning workshops for reducing implicit stereotyping of Hispanics by majority and minority group medical students. Stigma and Health, 5(1), 94–103. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000179

- Vora, Samreen MD, MHAM, FACEP; Dahlen, Brittany MSN, RN, NPD-BC, CPN, CCRN-K; Adler, Mark MD, FSSH; Kessler, David O. MD, MSc, FSSH; Jones, V. Faye MD, PhD, MSPH; Kimble, Shelita MEd, CHSOS; Calhoun, Aaron MD, FSSH Recommendations and Guidelines for the Use of Simulation to Address Structural Racism and Implicit Bias, Simulation in Healthcare: The Journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare: August 2021 - Volume 16 - Issue 4 - p 275-284 doi: 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000591