Head Injury

Objectives

Upon finishing this module, the student will be able to:

- Describe the different types of skull fractures.

- Describe the different types of intracranial hemorrhage.

- List the signs and symptoms of a concussion.

- Determine which children are low risk for clinically significant traumatic brain injury and can be discharged without imaging.

- Initiate treatment for children with head injuries in the emergency department.

Contributors

Update Authors: K. Mackenzie DuPont; and Mardient Rus, MD, MPH, DTM.

Original Author: Marideth Rus, MD.

Update Editor: Simi Jandhu, MD.

Last Updated: May 2024

Introduction

Head injury includes any injury to the scalp, skull, or brain. It is the most common type of injury requiring medical evaluation in children. Pediatric head injuries, which include traumatic brain injury (TBI), can have long term neurologic, cognitive, and behavioral consequences because they occur during brain development. Traumatic brain injuries are further classified as mild, moderate, or severe based on the initial Glasgow Coma Scale. While most injuries are mild with more limited long term sequelae, brain injury is the leading cause of death and disability in pediatric trauma patients.

A 14-year-old male presents to the emergency department (ED) after falling off a chest of drawers. He was sitting on top of his dresser, which his mother estimates is about three feet tall, when he lost his balance and fell forward, landing face down on the hardwood floor. He had no loss of consciousness, but his mother brought him in for evaluation because he has a large knot on his forehead and he threw up once in the car on the way over. In the ED, he endorses a mild frontal headache where he hit his head but is otherwise awake and alert. He has GCS of 15 and no external signs of trauma other than swelling over the right side of his forehead.

Initial actions will depend on the presentation of the child. Some patients will present many hours after the initial trauma and be ambulatory on arrival. Others may present unconscious from the scene of the injury. If there is any concern of possible cervical spine injury or if the patient has altered mental status limiting exam, the spine should be immobilized immediately and a cervical collar placed. A complete primary and secondary survey should be completed to ensure the patient is stable and to assess for any other injuries.

Assigning the child a Glasgow Coma Scale score should be performed as part of the initial evaluation and is considered to be part of the primary survey. Scoring for children and adults is the same, but infants and preverbal children must be assessed differently.

Glasgow Coma Scale for Children/Adults and Infants

| Activity | Score | Child / Adult | Score | Infant |

| Eye Opening | 4 | Spontaneous | 4 | Spontaneous |

| 3 | To Speech | 3 | To Speech/Sound | |

| 2 | To Pain | 2 | To Pain | |

| 1 | None | 1 | None | |

| Verbal | 5 | Oriented | 5 | Coos/Babbles |

| 4 | Confused | 4 | Irritable Cry | |

| 3 | Inappropriate | 3 | Cries to Pain | |

| 2 | Incomprehensible | 2 | Moans to Pain | |

| 1 | None | 1 | None | |

| Motor | 6 | Follows Commands | 6 | Spontaneous |

| 5 | Localizes to Pain | 5 | Withdraws to Touch | |

| 4 | Withdraws to Pain | 4 | Withdraws to Pain | |

| 3 | Abnormal Flexion | 3 | Abnormal Flexion | |

| 2 | Abnormal Extension | 2 | Abnormal Extension | |

| 1 | None | 1 | None |

There is a wide spectrum of presentations for children with head injuries. Some children will have only scalp hematomas, while others will suffer severe intracranial injuries and present with coma or seizures. Important injuries to consider in children with head trauma include skull fractures, intracranial hemorrhages, and concussion. It is also important to maintain a high index of suspicion for abusive head trauma, particularly in non-ambulatory and/or non-verbal children.

Skull Fractures

Skull fractures are more common in infants than in older children, with the parietal bone being the most commonly fractured bone and the frontal bone being the least commonly fractured. There are three categories of skull fractures:

- Linear Skull Fractures: May have an overlying hematoma, but bony abnormalities are rarely palpated.

- Depressed Skull Fractures: May be palpable on exam, with a depression or step-off felt when the skull is palpated.

- Basilar Skull Fractures: Fractures to the base of the skull, and can include the temporal bone, occipital bone, sphenoid bone, or ethmoid bone. Although rare, these fractures require additional evaluation as they can result in tears in the meninges leading to leakage of cerebrospinal fluid. Patients with basilar skull fractures may have physical exam findings including raccoon eyes (periorbital ecchymosis in the absence of a direct blow to the face), Battle's sign (ecchymosis over the mastoid process), hemotympanum, or drainage of cerebrospinal fluid from the nose.

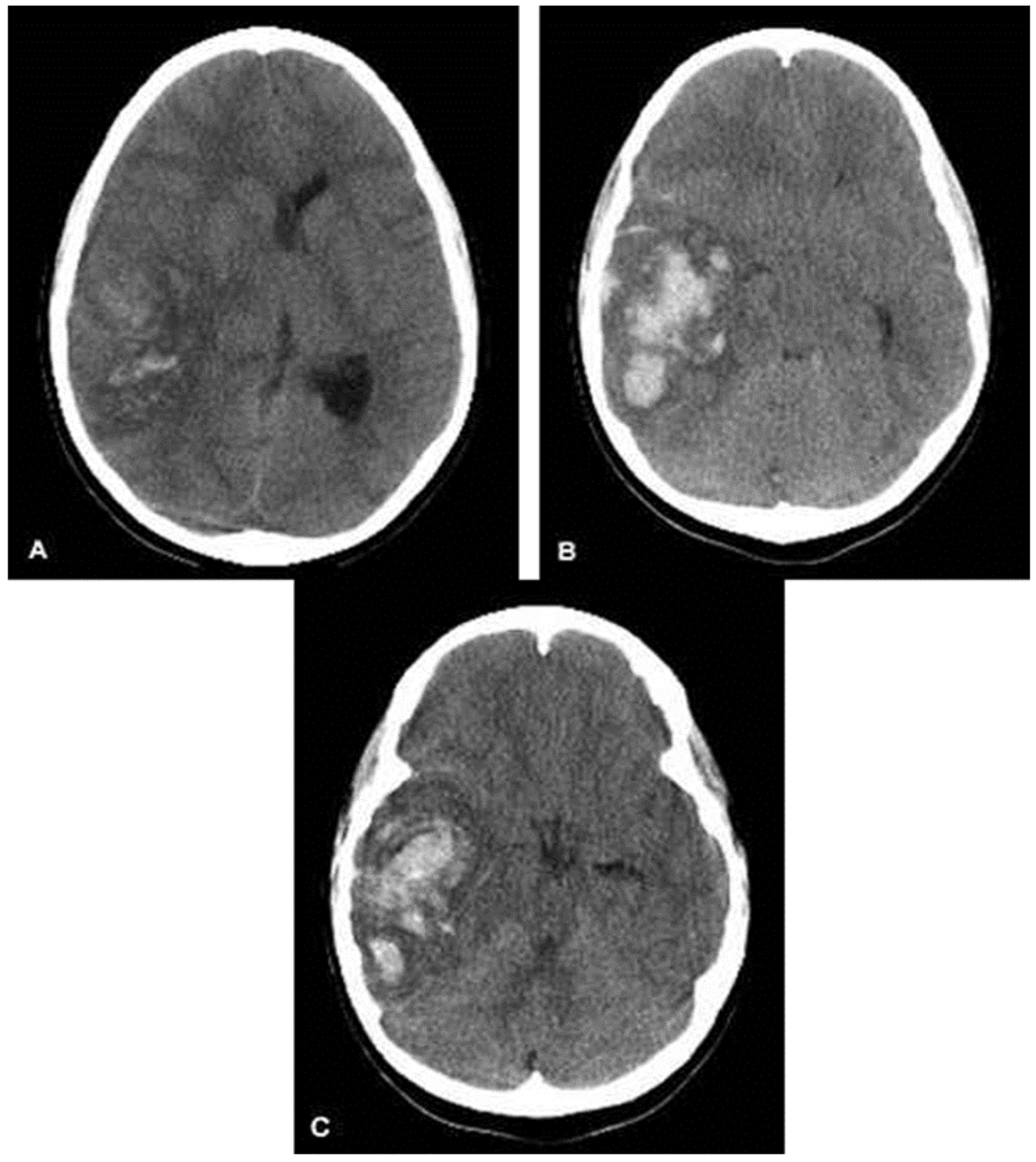

Intracranial Hemorrhage

Children with intracranial hemorrhage may present with a variety of symptoms, including headaches, frequent vomiting, and altered mental status. Intracranial hemorrhage should be suspected in any patient presenting to the ED with decreased level of consciousness. There are four types of intracranial hemorrhage:

- Epidural Hematomas: Occur when there is bleeding into the space between the skull and the dura mater. CT scan will show a convex, lens-shaped collection of blood. Blood generally does not cross suture lines. Many of these hemorrhages are caused by laceration of the middle meningeal artery, although venous bleeds can also occur. The classic presentation is a brief loss of consciousness with the trauma, followed by a lucid period and then deterioration. As epidural hematomas can accumulate rapidly, patients may change quickly and a timely diagnosis and neurosurgical intervention are key.

Figure: Epidural hematoma. Image courtesy of Jpogi. Image used under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

- Subdural Hematomas: Occur when there is bleeding into the space between the dura and arachnoid membranes. They appear as concave or crescent-shaped collections of blood on CT scan and can cross suture lines. These are generally caused by tears to the bridging veins between the cortex and venous sinuses. The hemorrhage occurs more slowly than in epidural hematomas, although still over a period of a few hours.

Figure: Subdural hematoma. Image courtesy of Dr. James Heilman. Image used under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

- Subarachnoid Hematomas: Occur when there is bleeding into the space between the arachnoid membrane and the pia mater that surrounds the brain.

Figure: Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Image courtesy of Dr. James Heilman. Image used under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

- Intraparenchymal Hemorrhages: Occur when there is tearing of intraparenchymal blood vessels. Depending on the size, these can also cause mass effect and midline shift, and may be more difficult to manage surgically than extra-axial hemorrhages.

Figure: Intraparenchymal Hemorrhage. Image courtesy of MD Computed Tomography diagnostic team. Image used under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

When evaluating a CT scan with an intracranial hemorrhage, it is important to not only identify the type of hemorrhage, but also to note the size and whether the lesion is causing mass effect or midline shift.

Concussion

Concussion has been defined as a disturbance in brain function caused by a direct or indirect force to the head. Patients with concussion may present with a variety of symptoms, but imaging is unremarkable on these patients. A concussion should be suspected in a patient with recent head trauma who complains of headache, vomiting, unsteadiness, confusion, or other abnormal behaviors. Several tools exist to help team trainers and physicians evaluate patients with concussions, including the Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 5 or SCAT5.

One of the most difficult decisions when a child presents with a head injury is whether or not the child requires a CT scan to evaluate for fracture or intracranial injury. If the child presents with an abnormal neurologic exam or decreased level of consciousness, the decision is usually straightforward and imaging is ordered immediately. However, many children present after a head injury with complaints such as loss of consciousness, brief period of appearing “dazed”, vomiting, or scalp hematoma, but are alert and active on exam. It is more difficult determining which of these children require imaging.

In 2009, the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) published an article that has been used to help practitioners identify children at very low risk of clinically significant brain injuries following head trauma. The study evaluated 42,412 children under the age of 18 and GCS of 14-15 presenting to the ED for evaluation of head trauma. This study includes suggested algorithms to be used to identify those children who meet low risk criteria for a clinically significant brain trauma and can therefore be discharged without a CT scan. The criteria are different for children under two years and for those two years or older. The algorithm is available here.

Low risk criteria for children less than two years of age include an absence of any of the following:

- GCS 14 or less, or other signs of altered mental status.

- Palpable skull fracture.

- Occipital, parietal, or temporal scalp hematoma.

- History of loss of conscious > five seconds.

- Severe mechanism of injury.

- Not acting normally per the parent.

Low risk criteria for children two years of age or older include absence of any of the following:

- GCS 14 or less, or other signs of altered mental status.

- Signs of basilar skull fracture.

- History of loss of consciousness.

- History of vomiting.

- Severe mechanism of injury.

- Severe headache.

If children meet NONE of these criteria, they have a very low risk of clinically important traumatic brain injury, and can be discharged without CT. If children do have low GCS, altered mental status, or signs of skull fracture, CT head is recommended. For children who have GCS 15, normal mental status, and no signs of skull fracture, but do have another risk factor, a period of observation vs CT scan may be considered, although observation is typically preferred.

Once a decision has been made to observe rather than obtain a CT scan, the question is always, "how long do I need to watch the patient?" A large study of children with mild head injuries found that the vast majority of children with intracranial hemorrhages will have worsening symptoms within six hours of the trauma. If children still appear well after a six hour observation period, they may be discharged home with instructions to return if the child is showing worsening symptoms.

Treatment depends on the severity of the injury. It is important to ensure that all children with head injuries have adequate blood pressures and oxygen saturations, as hypoxia and hypoperfusion of the brain may cause additional damage following a head injury. The head of the bed should be elevated to 30 degrees if there are any signs of increased intracranial pressure.

Linear skull fractures with no underlying hemorrhage will generally heal well and do not require admission if the child is otherwise well. Children with depressed skull fractures or basilar skull fractures should be evaluated by a neurosurgeon. Physicians should always keep the possibility of child abuse/maltreatment in mind when evaluating a child who sustains a skull fracture.

Intracranial hemorrhages should be evaluated by a neurosurgeon to determine if surgical intervention is indicated. Patients with small hemorrhages are often admitted for observation and supportive care, while those with large hemorrhages may go immediately to the operating room for drainage. For those with elevated intracranial pressure (ICP), hypertonic saline or mannitol may be used to lower ICP. It is important to ensure that the patient has been volume resuscitated prior to use of mannitol as it will cause diuresis. If there are signs of impending herniation, hyperventilation can be used temporarily while other treatment options are evaluated. Management of ICP includes:

- Elevation of head of bed.

- Hyperosmotic agents (hypertonic saline or mannitol).

- Hyperventilation.

- Antiemetics (if vomiting).

For more mild head injuries, supportive care with ondansetron for vomiting and acetaminophen or ibuprofen for headaches may be adequate. Children with concussions who participate in sports should not return to play until they are symptom free, and when they do return to play, they should gradually progress from light exercise to full contact sport participation rather than immediately returning to full play. All children with concussions should be cleared by either a physician or a qualified team trainer prior to returning to sports, and it is important to communicate this to families before they leave the emergency department. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) provides guidance on managing return to activities post-concussion here.

- The classic presentation for epidural hematomas is loss of consciousness followed by a lucid period and then deterioration, while the presentation for subdural hematomas is gradually worsening mental status over time.

- Patients with isolated linear skull fractures can often be discharged, while those with depressed or basilar skull fractures require evaluation by a neurosurgeon.

- Children who meet certain criteria have a very low risk of clinically significant brain injury and can be discharged without imaging.

- Children with concussion should not return to play until symptom-free, and should follow a gradual progression to full activity.

The patient was observed for a total of six hours after the incident. During that time he had one additional episode of emesis, which improved with anti-emetics. He took a nap, was able to PO, and overall felt much improved with acetaminophen for pain and ondansetron for nausea control. His GCS remained 15/15, and he had a normal neurologic exam. He was discharged home to follow up with his pediatrician if he developed any symptoms of concussion such as ongoing headaches, nausea, photophobia, difficulty sleeping, and trouble paying attention.

- Gelineau-Morel RN, Zinkus TP, Le Pichon JB. Pediatric Head Trauma: A Review and Update. Pediatrics in Review. 2019 Sep 1.

- Hamilton M, Mrazik M, Johnson DW. Incidence of Delayed Intracranial Hemorrhage in Children After Uncomplicated Minor Head Injuries. Pediatrics. 2010.

- Haydel M, Weisbrod LJ, Saeed W. Pediatric Head Trauma. StatPearls. 2024.

- Kupperman N, Holmes JF, et al. Identification of Children at Very Low Risk of Clinically-Important Brain Injuries After Head Trauma: A Prospective Cohort Study. Lancet. 2009.

- Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 5. Concussion Awareness Training Tool.