Shock

Objectives

Upon finishing this module, the student will be able to:

- Describe the signs and symptoms of shock.

- Discuss the initial management of shock.

- List the different types of shock and how to differentiate each type.

- List the laboratory and diagnostic tools helpful in the diagnosis of pediatric shock.

Contributors

Update Authors: Sam Dillman, MD; and Jamie Hess, MD.

Original Authors: Holly Caretta-Weyer, MD; and Jamie Hess, MD.

Update Editor: Adedoyin Adesina, MD.

Last Updated: XX

Introduction

Shock is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in children. Shock is a term used to describe inadequate oxygen delivery to tissues that cannot keep up with metabolic demand, creating a state of hypoperfusion. It may be uncompensated, meaning there is hypotension and an inability to maintain normal perfusion, or it may be compensated with blood pressure being maintained by increasing heart rate and increasing vascular resistance.

Without hemodynamic support, lack of perfusion results in a refractory stage culminating in multi-organ failure and death.

Hypovolemic shock secondary to vomiting and diarrhea is the most prevalent type of pediatric shock, which accounts for 9% of mortality globally in pediatric patients younger than five years. Septic shock results in the highest mortality rate ranging from 40-60% in pediatric shock. The World Health Organization’s 2020 global report estimated that 20% of all global deaths were from sepsis with half of those deaths in children younger than five years. The most common forms of shock in neonates include birth trauma, infectious diseases, and congenital heart disease.

Assessing the ABC’s (airway, breathing, circulation) is the critical first step for a patient with shock. Place the child on a cardiorespiratory monitor, pulse oximeter, and obtain a blood pressure. Also, obtain a point-of-care glucose. Start supplemental oxygen and consider early intubation if the child will require ventilatory assistance, significant help with oxygen demand, or airway protection. Obtain IV access; if you cannot after two attempts, an intraosseous line is appropriate as access is paramount in shock states.

Once you have managed the airway and breathing, circulation becomes key in shock. First, you must identify the type of shock, which may not always be easy in mixed shock states (see differential diagnosis). The key component of resuscitation in patients presenting in shock is fluid administration. In most cases of decompensated distributive or hypovolemic shock, the most important first step is to give a 20 mL/kg bolus of IV crystalloid (normal saline or lactated ringers). This may be repeated twice up to a total fluid administration of 60 mL/kg. If the child remains in shock, this is considered refractory shock and it would then be prudent to consider adding vasopressor support, often in the form of norepinephrine or epinephrine. If a child has risk factors for adrenal insufficiency, one should also consider administering stress-dose steroids as adrenal insufficiency can also lead to a refractory shock state. If the child is suffering from hemorrhagic shock, blood should be administered after the initial crystalloid bolus or immediate blood products are accessible and the site of hemorrhage should be managed appropriately.

Cardiogenic shock is a special type of shock in which there is failure of the pump due to malformation, overload, obstruction, or a non-perfusing rhythm. Fluid may still be given in this instance but at a lower bolus (5-10 cc/kg) and over a longer period (up to 20 minutes) to prevent exacerbation of the failure state and worsening pulmonary edema. You should closely monitor fluid and respiratory status during fluid administration in this instance. If you are suspicious of a ductal-dependent cardiac lesion or anomaly, which can cause an obstructive shock picture with cardiogenic shock, you should also consider administering prostaglandin to open the ductus arteriosus which can ease the amount of vascular congestion and fluid backing up into the lungs.

Goals for Resuscitation

- Blood pressure (systolic pressure at least fifth percentile for age: 60mmHg < one month of age, 70mmHg + [2 x age in years] in children one month to ten years of age, 90mmHg in children ten years or older).

- Quality of central and peripheral pulses (strong, distal pulses equal to central pulses).

- Skin perfusion (warm, with capillary refill under two seconds).

- Mental status (normal mental status).

- Urine output (> 1mL/kg/hr once effective circulating volume is restored).

- Clearance of lactate (down trending and preferably reduced by half after initial resuscitation).

Shock is a clinical diagnosis and is broken down into different types: hypovolemic, cardiogenic, distributive, obstructive, and dissociative shock. It is often divided into "warm shock" and "cold shock." In "warm shock," decreased vascular resistance may result in bounding pulses, warm extremities, and widened pulse pressure. In "cold shock," decreased cardiac output results in compensatory increased vascular resistance associated with weak distal pulses, prolonged capillary refill, cool extremities, and a narrow pulse pressure. Children can change from one shock category to another.

Hypotension is the hallmark late sign of shock in children. Other late signs include prolonged capillary refill (> four-five seconds) and worsening mental status. Bradycardia and apnea are very late signs of shock.

Hypovolemic Shock

Systemic vascular resistance is increased with initially stable to possibly decreased cardiac output at later stages. The extremities become cool, making this an example of "cold shock." Causes of hypovolemic shock include gastroenteritis, hemorrhage, burns, third spacing, and renal losses. Different stages of hypovolemic shock have different associated physical exam findings and vital signs.

| Class I (very mild) | Class II (mild) | Class III (moderate) | Class IV (severe) | |

| Percent blood volume loss | < 15% | 15-30% | 30-40% | > 40% |

| Heart rate | Normal | Slightly increased | Moderately increased | Markedly increased |

| Respiratory rate | Normal | Slightly increased | Moderately increased | Markedly increased, markedly decreased, or absent |

| Blood pressure | Normal or slightly increased | Normal or slightly decreased | Decreased | Decreased |

| Pulses | Normal | Normal or decreased peripheral | Weak or absent peripheral | Absent peripheral, weak or absent central |

| Skin | Warm and pink | Cool extremities, mottled | Cool mottling extremities or pallor | Cold extremities with pallor or cyanosis |

| Capillary refill | Normal | Prolonged | Markedly prolonged | Markedly prolonged |

| Mental status | Slightly anxious | Mildly anxious, confused, combative | Very anxious, confused or lethargic | Very confused, lethargic, or comatose |

| Urine output | Normal | Slightly decreased | Moderately decreased | Markedly decreased or anuria |

Distributive Shock

Distributive shock often results from vasodilation and a decrease in systemic vascular resistance. It is associated with normal to increased cardiac output. Given the vasodilation, the extremities are warm and makes this an example of "warm shock." Causes of distributive shock include:

- Sepsis: Infection causes significant vasodilation. Consider in a child with a fever and source of infection.

- Anaphylaxis: Causes profound vasodilation secondary to an IgE-mediated immediate hypersensitivity reaction. Symptoms include wheezing, urticaria, angiodema, and stridor.

- Neurogenic: Spinal cord injury resulting in loss of sympathetic tone, resulting in vasodilation as well as bradycardia. Consider a trauma patient with neurological deficits and paradoxical bradycardia in the setting of hypotension.

Cardiogenic Shock

Cardiogenic shock results from pump failure and depressed cardiac output. This decreased cardiac output results in cool extremities, marking it as another example of "cold shock." Common causes of cardiogenic shock in children include:

- Structural Disorders: Consider in children with hepatomegaly, signs of pulmonary edema, JVD, or murmur. Some of these disorders are ductal-dependent, meaning they will only manifest after closure of the duct, while others are ductal-independent and will present within the first day or two of life.

- Cardiomyopathies: Consider in children with recent infection, murmur, chest pain, dizziness, or syncope.

- Arrythmias: Prolonged SVT or ventricular dysrhythmias can cause substantial decrease in stroke volume and thus cardiac output.

Obstructive Shock

The clinical signs of obstructive shock include tachycardia, cool extremities, and increased central venous pressure due to a mechanical obstruction of cardiac output. Often, it will present in a similar fashion to cardiogenic shock. Different forms of obstructive shock include tension pneumothorax, cardiac tamponade, pulmonary embolism, or congenital lesions.

Dissociative Shock

Occurs due to the inability to release delivered oxygen. Clinical signs include tachycardia, altered mental status, and fatigue. Different forms of dissociative shock include carbon monoxide poisoning, methemoglobinemia, or cyanide poisoning.

Lactate

Lactate levels are a valuable indirect marker of tissue hypoperfusion. A high lactate level is correlated with increased mortality. A lactate level greater than 18mg/dL (> 2mmol/L) is considered a marker of cellular/metabolic dysfunction. Although optimal levels of hyperlactatemia have not been fully defined in pediatrics, children in a shock state can have normal levels. Decreasing lactate levels over time can be used to help track response to therapy.

Mixed Venous Oxygen Saturation

This can be helpful in assessing the whole-body oxygen consumption to oxygen delivery ratio. A normal mixed venous oxygen saturation should be >70%. This is not frequently measured in the ED.

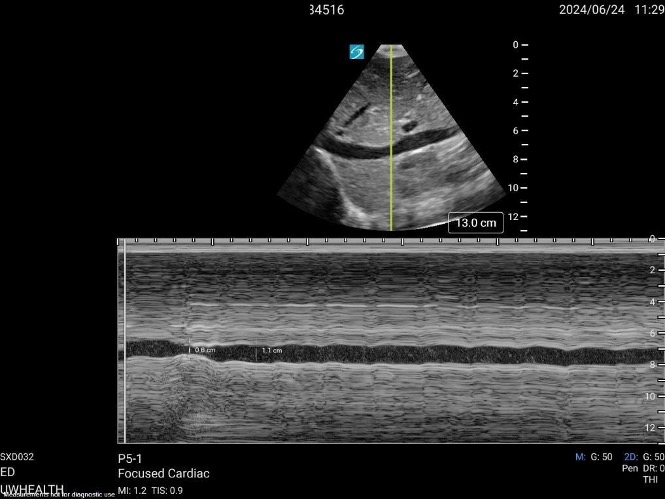

Point-of-Care Ultrasound (POCUS)

Rapid ultrasound for shock and hypotension (RUSH) protocols can be adapted for pediatric practice.

- Echocardiogram: A focused cardiac examination can help provide information on ventricular function, presence of pericardial effusion, and evidence of right heart strain.

- Inferior Vena Cava Evaluation: The ratio of the IVC (the caval index) to the aorta or the respiratory variation/collapsibility of the IVC can be correlated with hydration status. Variation in IVC diameter during respiration of >50% combined with an easily collapsible vessel suggests a low-volume state. In contrast, a variation of <50% with a distended or minimally collapsible IVC suggests a high-volume state or potential tamponade/obstructive physiology. In pediatrics, the IVC/aorta ratio can also be utilized. A ratio of less than one is seen in a low-volume state.

- Lung Ultrasound: Can assess pneumothorax and fluid overload during volume resuscitation.

- Abdominal: Can assess for intra-abdominal and pelvic free fluid.

Figure: Subcostal view of the IVC in M-mode. Picture courtesy of Samuel Dillman, MD.

Shock Video 1 Tranverse IVC and Aorta

Video: IVC/Aorta Ratio. Video courtesy of Samuel Dillman, MD.

The suspected etiology of shock can help target further laboratory evaluation.

- Infection: Cultures (blood, urine, and CSF as indicated), procalcitonin, CBC.

- Trauma: CBC (hemoglobin level may lag in hemorrhagic shock), coagulation studies.

- Endocrine: Cortisol, calcium, thyroid, glucose, ammonia.

- Cardiogenic: BNP, troponin.

- Dissociative: Carboxyhemoglobin, cyanide level.

Other monitoring tools in shock include:

- Near-Infrared Spectroscopy: A noninvasive monitor that can provide information about tissue oxygenation.

- CVP Monitoring: Low central venous pressure (< 3mmHg) can be seen with hypovolemia and distributive shock. High values (> 10mmHg) can be seen with cardiac shock and high intrathoracic pressure.

- Arterial Catheter: Provides real-time information regarding blood pressure management.

Volume resuscitation, vasopressors, and identifying reversible causes are mainstays in the treatment of shock. In pediatrics, epinephrine and norepinephrine are the recommended vasopressors. Dopamine has fallen out of favor as a first line agent based on multiple clinical trials.

- Norepinephrine as an α-1 agonist is used as a vasoconstrictor in "warm shock."

- Epinephrine, an inotropic β-1 agonist, is used to improve cardiac contractility in low cardiac output states.

- Hydrocortisone can be considered in vasopressor and fluid refractory hypotension.

- Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support may also be required for refractory cardiac failure.

Rule of 50s when dosing glucose in hypoglycemic pediatric patients:

- 1mg/kg of D50 (1x50=50)

- 2mg/kg of D25 (2x25=50)

- 5mg/kg of D10 (5x10=50)

Specific considerations in different types of shock, in addition to volume resuscitation and vasopressors:

- Cardiac Shock: 10mL/kg fluid boluses should be given while monitoring symptoms of fluid overload. In significant diastolic dysfunction, milrinone can help improve inotropy and reduce afterload. In patients with pulmonary hypertension, systemic pulmonary vasodilators such as oxygen and nitric oxide can be utilized.

- Hemorrhagic Shock: Balanced repletion of blood components, institution-based massive transfusion protocols, and source control.

- Anaphylactic Shock: Prompt management with intramuscular epinephrine and may require an epinephrine infusion for refractory causes.

- Neurogenic Shock: Norepinephrine is the first-line vasoactive agent due to its both α and β activity, effectively addressing hypotension and bradycardia. Phenylephrine is also utilized in neurogenic shock due to the α-1 vasoconstriction but can cause reflex bradycardia due to lack of β activity. Atropine may be required in severe bradycardia.

- Septic Shock: Early empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics and avoidance of hypoglycemia. In rapid sequence intubation, it is important to avoid etomidate as it can cause adrenal suppression.

- Obstructive Shock: Requires alleviation of causative obstruction (e.g. tension pneumothorax, pericardial tamponade, pulmonary embolus).

Disposition

Most patients who present with shock will require admission to a pediatric intensive care unit for close monitoring, frequent reassessment, and further management. Early consultation with an intensivist is recommended, and you may need to contact other specialists, including surgeons in the case of trauma or cardiology for cardiac defect.

- Shock is often difficult to recognize. Sometimes patients may present with obvious signs of shock, and other times it is very subtle (compensated shock). Pay close attention to physical exam findings and vital signs with careful history-taking.

- In shock, don't forget about the glucose. Pediatric patients are often hypoglycemic when critically ill and may require glucose supplementation.

- Avoid inadequate monitoring of treatment response. Make sure you fully resuscitate the patient to the parameters outlined above, but be careful not to under-fluid resuscitate those who are hypovolemic and not to over-fluid resuscitate those in cardiogenic shock.

- Always consider causes for lack of improvement such as other causes of shock or other contributing factors (adrenal insufficiency) in refractory shock.

- Bell LM. Shock. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2010.

- Bjorklund A, et al. Pediatric Shock Review. Pediatr Rev. 2023 Oct 1.

- Carcillo JA, et al. Role of Early Fluid Resuscitation in Pediatric Septic Shock. JAMA. 1991.

- Carcillo JA, Fields AI. Clinical Practice Parameters for Hemodynamic Support of Pediatric and Neonatal Patients in Septic Shock. Critical Care Medicine. 2002.

- Hardwick JA, Griksaitis MJ. Fifteen-Minute Consultation: Point of Care Ultrasound in the Management of Paediatric Shock. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2021 Jun.

- Chameides L, et al. Recognition of Shock. Pediatric Advanced Life Support Provider Manual. American Heart Association. 2011.

- Rivers E, et al. Early Goal-Directed Therapy in the Treatment of Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001.

- Stoner MJ, et al. Rapid Fluid Resuscitation in Pediatrics: Testing the American College of Critical Care Medicine Guideline. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2007.

- Witte MK, et al. Shock in the Pediatric Patient. Advanced Pediatrics. 1987.