Perforated Viscus

Dr. Amy Cutright, Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, Nebraska

Editor: Dr. Rahul Patwari, Rush University, Chicago, Illinois

Last Updated: 2019

Case Study

Anne is a 65-year-old female who presents to your Emergency Department for abdominal pain. She notes severe non-radiating left lower quadrant abdominal pain for two days gradually worsening. Prior to this she has constipation for approximately two weeks and her last bowel movement was three days ago with rare flatus. She notes low grade fevers, chills, nausea and two episodes of non-bilious and non-bloody vomiting. She has no appetite and has only had small sips of water over the past day. She pain is worse with movement, coughing, and eating. She has tried acetaminophen for pain with no relief. She has a history of non-insulin dependent diabetes and hypertension. She has had a remote appendectomy and complete hysterectomy.

Anne appears ill and very uncomfortable on exam. VS: T 39°C, P 114 beats/minute, BP 132/88 mmHg, RR 22 breaths/minute, SpO2 94% on room air. Cardiopulmonary exam is remarkable only for tachycardia and tachypnea. She is tender in all quadrants but exquisitely so in the left lower quadrant. There is rebound and involuntary guarding, as well as decreased bowel sounds in all quadrants. There are no masses or hernias.

What is your differential diagnosis and management plan?

Objectives

- Upon finishing this module, the student will be able to:

- Recognize the severity of perforated viscus and the need for rapid treatment.

- Relate the common causes of perforated viscus.

- Describe the classic presentation and physical exam of patients with perforated viscus.

- Discuss the reliability of the various radiographic modalities in the evaluation of perforated viscus.

- Describe the treatment for perforated viscus.

Introduction

Perforated hollow viscus is a life-threatening cause of abdominal pain and carries a mortality of 30-50%. This diagnosis is first suspected on through a careful history, a thorough examination, attention to abnormal vital signs, and a broad differential diagnosis in ill patients with abdominal pain. Rapid treatment, resuscitation and surgical consultation should be initiated when the diagnosis is suspected.

It is essential to consider other life-threatening causes of abdominal pain when evaluating patients who are ill appearing with an acute abdomen. Early presentation of many of the causes of acute abdomen can be similar and difficult to distinguish. Do not exclude the possibility of abdominal aortic aneurysm, gastrointestinal bleeding, pancreatitis, bowel obstruction, volvulus in any form, mesenteric ischemia, incarcerated/strangulated hernia or intra-abdominal infection. It is also important to consider pelvic sources in female patients, namely gynecological infections and ruptured ectopic pregnancy. Perforated viscus can result from many processes (see list below).

Foreign body perforation

- Penetrating trauma

- Endoscopy/iatrogenic

- Ingestion of foreign objects

Extrinsic bowel obstruction

- Gastrointestinal stromal tumors

- Lymphoma

- Surgical adhesions

- Hernia

- Volvulus

Intrinsic bowel obstruction

- Bezoar

- Crohn disease stricture

- Diverticulitis/appendicitis

- lntra-luminal neoplasm

Toxicologic

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatories

- Salicylates

- Acid/Alkali ingestions

Loss of gastrointestinal wall integrity

- Peptic ulcer

- Crohn disease

- Tumor lysis syndrome

Gastrointestinal ischemia

- Mesenteric ischemia

- Portal vein thrombosis

Infection

- Salmonella typhi

- Clostridioides difficile (previously termed Clostridium difficile)

- Cytomegalovirus

Initial Actions and Primary Survey

The initial approach to a suspected perforated viscous may include, but are not limited to:

- Cardiac monitoring, continuous pulse oximetry, large bore IV access

- Begin fluid resuscitation

- Focused history and physical examination

- Begin broad spectrum antibiotics

- Rapid consultation of surgical services

Ill patients in whom perforated viscus is suspected require rapid and aggressive treatment. Obtain large bore IV access and start IV fluid resuscitation with crystalloid fluids (normal saline or lactated ringers). Begin broad spectrum antibiotics. Do not limit your differential diagnoses for these patients prematurely. The initial stages of treatment and diagnostic evaluation for perforated viscus and other causes of life-threatening abdominal pain overlap. This allows for the simultaneous assessment and resuscitation of the critically ill patient.

Presentation

Severe abdominal pain is the presenting complaint in patients with perforated viscus, with very remote exception” (elderly, debilitated, disabled, paraplegic/quadriplegic). The onset of pain is sudden and accompanied by rapidly worsening overall condition. The patient will frequently relate a prior abdominal pain history that is less severe due to the underlying cause of the perforation (gastrointestinal ulcer, appendicitis, diverticulitis, malignancy, prior surgery, etc.).

The perforation results in leakage of air, gastrointestinal contents, and bacterial toxins into the peritoneal cavity resulting in generalized inflammation and peritonitis. A systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) begins due to the gross abdominal contamination. Patients will present ill appearing with varying degrees of fever, tachycardia, tachypnea and hypotension to refractory septic shock. Patients may present on a septic spectrum beginning with a Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS), progressing to Sepsis, evolving into Severe Sepsis, and transitioning into septic shock. Patients may present in any one of these stages. Their condition may vacillate between several of these stages during the course of ED care. See the Sepsis chapter for more details.

Patients suffering from perforated viscus have an ill to toxic appearance. Depending on time of presentation the physical exam of the abdomen may range from focal tenderness to a rigid acute abdomen. Early perforation usually shows focal tenderness near the site of the perforation. As the leakage continues, peritonitis ensues resulting in the generalized tenderness, rebound, voluntary/involuntary guarding and rigidity. Patients with diffuse peritonitis will prefer to remain immobile as any jarring of the abdomen including movement of the stretcher, walking, deep breathing/coughing, movement of lower extremities and heel thump results in intense pain and tenderness.

The presentations of perforated viscus can be altered in patients with delayed presentation, immunocompromised state or who are elderly. In those patients in whom an intra-abdominal abscess has formed to contain the infection, for example as in perforated appendicitis, the history may stretch out several days and the physical may demonstrate focalized tenderness and rebound. Immunocompromised and elderly patients often have an unimpressive exam or vital signs but pain out of proportion to physical exam. Thus, maintain a high level of suspicion in elderly and immunocompromised patients as their deceptively mild presentations are coupled with a higher baseline risk of developing perforation.

Diagnostic Testing

Laboratory evaluation for patients with perforated viscus begins with standard tests for abdominal pain: complete blood count with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel, lipase, urinalysis and urine pregnancy test (when applicable). The focus of these tests is to obtain initial hemoglobin, hematocrit, platelet counts, leukocytosis/leukopenia and obtain liver and kidney function. Lipase can help to exclude severe pancreatitis as an alternative diagnosis. Type & screen or type & cross, coagulation panels and EKG will frequently be needed both for future operative planning.

Choice of radiographic modality in suspected perforated viscus depends on the patient’s condition. It is important to understand that the advantages and limitations of each of these modalities so that perforation is not prematurely excluded from your differential due to an unreliable image.

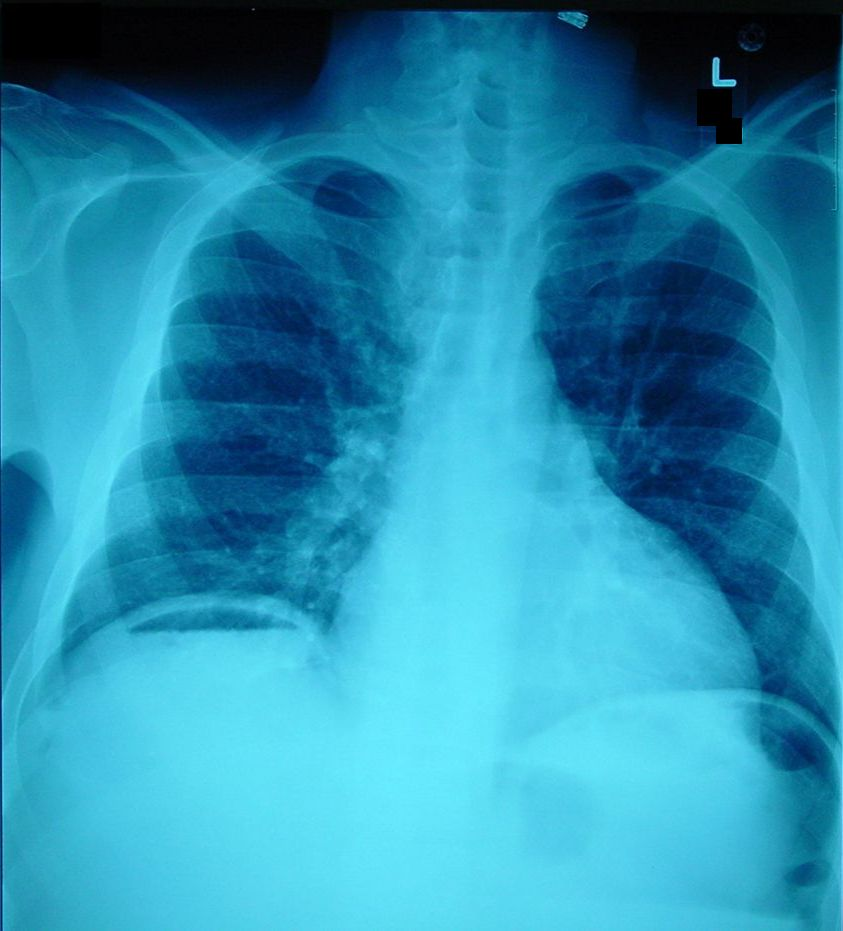

Plain Radiograph

Plain radiograph (upright and supine abdomen view + upright chest view OR lateral decubitus view) has the advantages of being performed rapidly and at the bedside. It can be obtained in unstable patients without moving them from ED while resuscitation is ongoing.

Image source: http://clinicalcases.blogspot.com/2004/03/bloody-ascites-and-gas-under-diaphragm.html. Used under the Creative CommonsAttribution-ShareAlike 4.0. No changes were made.

However, radiograph for pneumoperitoneum is limited because it misses free air in a large portion of patients depending on the amount of air present and the quality of the film. The literature varies, however the most optimistic statistics for plain radiographs and pneumoperitoneum are as follows: 53% sensitivity, 78% specificity, 95% PPV, 20% NPV. Placing the patient in the upright or lateral decubitus views for 10 minutes before taking the image improves the likelihood of seeing free air. One study demonstrated that laparotomy-proven perforated viscous had radiographs with free air only 50% of the time. Additionally, they showed free air without actual perforation after exploratory surgery in 14% of cases. The absence of pneumoperitoneum on plain radiographs in patients suspected of having perforated viscous does NOT exclude the diagnosis and further evaluation is needed.

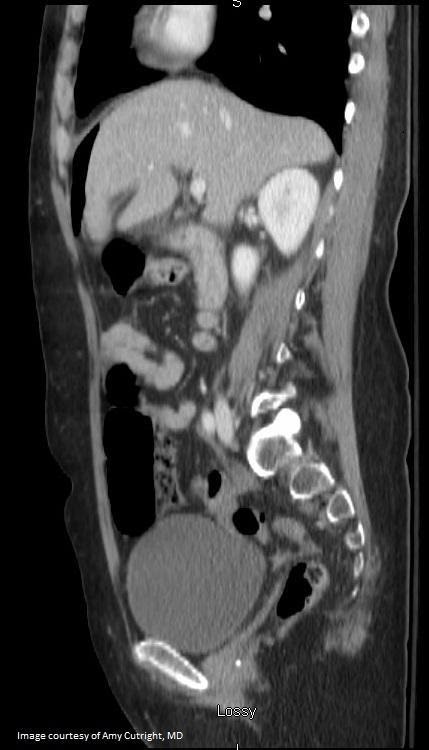

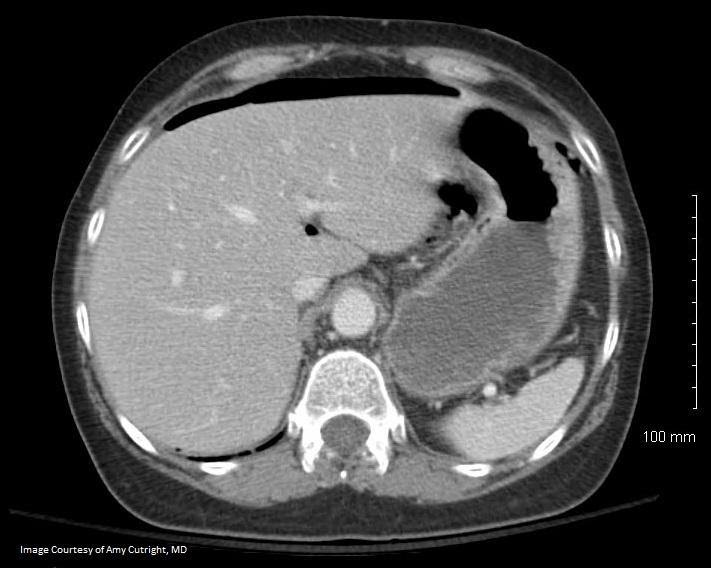

Computed Tomography Scan

CT abdomen/pelvis is the best radiographic assessment for free air. It detects even minute amounts of pneumoperitoneum. Additionally, CT scan can elucidate the source of the perforation including the retroperitoneum and demonstrates other causes of acute abdomen outside of perforated viscous.

CT scan is limited as it takes longer and requires the patient to leave the ED. This modality will not be ideal in unstable patients who are refractory to resuscitative efforts. Intravenous contrast should in general be used in this scenario unless contraindicated, but oral contrast should be avoided as it will not give additional useful information and will delay image acquisition.

""CT Imaging of Pnemoperitoneum related to perforated viscus”. Red arrow denotes free air along the peritoneum Original Image created by Dr. Amy Cutright. Used by permission. Content provide by CC BY-NC-SA. No changes have been made. 2019

"CT Imaging of Pnemoperitoneum related to perforated viscus”. Red arrow denotes free air anterior to liver Original Image created by Dr. Amy Cutright. Used by permission. Content provide by CC BY-NC-SA. No changes have been made. 2019

“CT Imaging of Pnemoperitoneum related to perforated viscus”. Red arrow denotes free air along the liver border Original Image created by Dr. Amy Cutright. Used by permission. Content provide by CC BY-NC-SA. No changes have been made. 2019

Ultrasound

Ultrasound in the hands of the well trained provider is becoming more commonly used in the assessment of abdominal pain. It has been reliably used to assess for intra-abdominal fluid and abdominal aortic aneurysm which are potential causes of acute abdomen. Ultrasound can detect free air when utilized by an experienced and trained practitioner.

Treatment

Treatment of perforated viscous requires three major actions detailed below:

- Resuscitation

- Early antibiotics

- Early surgical consultation

Due to the exceptionally high morbidity and mortality, patients with perforated viscous are ill and require rapid intervention. These patients should be treated in the resuscitation or critical areas of the ED that allow for close monitoring and frequent reassessment. Continuous monitoring is required and treatment begins with managing basic ABCs.

Oxygen supplementation to invasive airway management may be needed depending on the patients pre-existing conditions, severity of illness and work of breathing. Obtain two large bore IVs and start IV fluid resuscitation to help with normalization of vital signs and to restore adequate tissue perfusion. Resuscitation needs may range from a single liter of fluids to massive volume administration. Blood products may need needed in some cases. Treat pain aggressively, but consider that non-synthetic opioids will cause histamine release and may worsen hypotension. In this case, fentanyl may be a better option although it has a shorter duration of action.

Begin antibiotics early in the workup. anti-microbial coverage will depend on the site of the perforation. If the location of the perforation is unknown empirically cover for gram negatives, gram positives and anaerobes. Common empiric regimens for abdominal sources include: ciprofloxacin + metronidazole, ceftriaxone + metronidazole, piperacillin/tazobactam, or imipenem.

Definitive management of perforated viscus requires general surgery intervention. Thus, early surgical consultation is warranted and in many cases initiated before the diagnosis is confirmed with imaging. The site of perforation must be identified and repaired and the gross abdominal contamination removed with large volume abdominal wash out. Some causes of perforation can be directly repaired, some will require omental or mesenteric patch and others can be contained with intra-abdominal drains from interventional radiology. The exact modality used will depend on the individual situation and will be determined by the surgeon.

Pearls and Pitfalls

- Begin aggressive resuscitation and antibiotics in patient suspected of perforation.

- Consult surgery early when perforation is suspected, even if confirmatory tests are not available.

- Do not rely on radiographs to rule in or rule out perforation.

- CT scan is the definitive test for evaluation of perforation but cannot be attained in unstable patients.

Case Study

Anne is placed on the monitor and large bore IV access is obtained. She is given intravenous normal saline bolus as well as IV pain and anti-emetic medication. Laboratory tests reveal a leukocytosis of 23,000 and a mild acute kidney injury. Urinalysis shows no evidence of a UTI. She undergoes a CT of her abdomen and pelvis which demonstrates perforated acute diverticulitis with abscess formation, and intravenous ciprofloxacin and metronidazole are started early. She is taken to the operating room with general surgery for repair and washout.

References

Langell JT, Mulvihill SJ. Gastrointestinal perforation and the acute abdomen. Med Clin North Am. 2008 May;92(3):599-625.

Winek TG, Mosely HS, Grout G, et al. Pneumoperitoneum and its association with ruptured abdominal viscus. Arch Surg 1988;123:709–12.

Roh JJ, Thompson JS, Harned RK, et al. Value of pneumoperitoneum in the diagnosis of visceral perforation. Am J Surg 1983;146(6):830–3.

Woodring JH, Heiser MJ. Detection of pneumoperitoneum on chest radiographs: comparison of upright lateral and posteroanterior projections. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995 Jul;165(1):45–47.

Williams N, Everson, NW. Radiological confirmation of intraperitoneal free gas. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. Jan 1997; 79(1): 8–12.

Chiu YH, Chen JD, Tiu CM, Chou YH, Yen DH, Huang CI, Chang CY. Reappraisal of radiographic signs of pneumoperitoneum at emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2009 Mar; 27(3):320-7.

Blaivas M, Kirkpatrick AW, Rodriguez-Galvez M, Ball CG. Sonographic depiction of intraperitoneal free air. J Trauma. 2009 Sep;67(3):675.

Mularski RA, Sippel JM, Osborne ML. Pneumoperitoneum: a review of nonsurgical causes. Crit Care Med. 2000 Jul;28(7):2638-44. Review.

Jones R. Recognition of pneumoperitoneum using bedside ultrasound in critically ill patients presenting with acute abdominal pain. Am J Emerg Med. 2007 Sep;25(7):838-41

Furukawa A, Sakoda M, Yamasaki M, Kono N, Tanaka T, Nitta N, Kanasaki S, Imoto K, Takahashi M, Murata K, et al. “Gastrointestinal tract perforation: CT diagnosis of presence, site, and cause.” Abdom Imaging. 2005 Sep-Oct; 30(5):524-34.

Grassi R, Romano S, Pinto A, Romano L. “Gastro-duodenal perforations: conventional plain film, US and CT findings in 166 consecutive patients.” Eur J Radiol. 2004 Apr; 50(1):30-6.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pneumoperitoneum_modification.jpg

Case courtesy of Dr Dayu Gai, <a href=”https://radiopaedia.org/”>Radiopaedia.org</a>. From the case <a href=”https://radiopaedia.org/cases/31407″>rID: 31407</a>