Spinal immobilization

Author Credentials

Author: Eric Blazar, MD, FACEP, Department of Emergency Medicine Inspira Medical Center-Vineland, Kyle Coupe, DO, MHSc, Department of Emergency Medicine Inspira Medical Center-Vineland.

Editor: Galeta Clayton, MD, Department of Emergency MedicineRush University,

Section Editor: Navdeep Sekhon, MD

Update: 2023

*All images courtesy of Rowan University SOM unless otherwise noted

Case Study

An otherwise healthy 33 year old male was the restrained driver in a vehicle going 25 mph when he looked down to check his cell phone and struck a 25 year old female cyclist who was crossing the street in front of him. Airbags were not deployed, the driver denied LOC and was ambulatory at the scene after self-extricating from the vehicle. Bystanders called EMS. The driver is complaining of right sided posterolateral neck pain but denies weakness or paresthesias. The cyclist is still on the ground screaming from pain. She has an obvious closed left femur deformity. Upon arrival, the EMTs placed both of them in cervical collars and rigid backboards prior to transporting them to the local Emergency Department for evaluation.

Objectives

By the end of this module, the student will be able to:

Discuss the indications for spinal immobilization and the impact that spinal immobilization can have on neurologic outcomes in trauma patients.

Discuss the two main procedures utilized to immobilize the spine of trauma patients (cervical collar and rigid spinal backboard).

Utilize decision rules to evaluate the spinal health of trauma patients.

Display proper use of a C-collar and backboard immobilization in the emergency department (ED).

Determine the most appropriate spinal imaging modality to use when indicated following traumatic injury.

Introduction

Spinal immobilization is one of the most common prehospital and ED procedures performed in the setting of trauma (ref.1). In practice, the spine is generally split into two distinct sections - the cervical spine (C-spine) and the thoracic/lumbar spine. Spinal immobilization is thus applied to either one or both of these areas, with placement of a cervical collar being the more common of the two.

For cervical spine immobilization, a hard cervical collar is applied. The purpose of the cervical collar itself is to place the spine in anatomical alignment with the appropriate alignment and cervical lordosis. Ideally, a cervical collar holds the neck

in place to stop flexion, extension and rotation of the spine, with the goal of preventing potential further movement of any spinal injuries and minimizing further injury to the spinal cord.

The figure below shows a rigid cervical

collar (left), not to be confused with a soft collar (right). The soft cervical collar does not immobilize or stabilize the cervical spine and should not be used for cervical spinal immobilization.

|  |

Figure 1. Rigid cervical collar (Left) and soft cervical collar (Right). James Heilman, MD - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0. Original image located on https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11918415.

Note: Soft collars are not appropriate in trauma or when considering an unstable cervical spine injury.

Thoracolumbar immobilization is achieved with the use of a rigid backboard. The rigid backboard is employed for immobilization of the remaining thoracic and lumbar spine, primarily for transport of the patient by EMS to the ED. Typically it is a large rectangular piece of hard plastic with attached adjustable straps designed to keep the trunk and extremities stable. The goal is to immobilize the patient in the supine position to allow for minimal compression on the spinal cord. Upon arrival to the ED, the patient should be transitioned off the rigid backboard as soon as reasonably possible, in order to prevent pressure ulcers or other injuries and to improve patient comfort. If there is concern for thoracolumbar spinal injury, manual immobilization precautions can be maintained without the rigid backboard.

Figure 2. Backboard used for spinal

immobilization. Image courtesy of RebelEM and used under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDervis 3.0 Unported License. Original image located at: Spinal Immobilization in Trauma Patients - REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.

Figure 2. Backboard used for spinal

immobilization. Image courtesy of RebelEM and used under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDervis 3.0 Unported License. Original image located at: Spinal Immobilization in Trauma Patients - REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.

Like everything we do in medicine, there are risks and benefits of spinal immobilization. It is appropriate for the practitioner to utilize their best judgment in utilizing these tools. In the past, it was thought that spinal immobilization was associated with improved neurologic outcomes in patients with spinal related traumas (ref.1). Much of the research in this area, however, is low quality and only demonstrates an association (not causation) between spinal immobilization and further injury prevention. There is currently no high level evidence (Class I) demonstrating that spinal immobilization contributes to improved neurologic outcomes.

Further, there is existing data that shows worse outcomes following spinal immobilization. Immobilization devices have been shown to lead to more difficult airways, inadequate physical examinations and the development of pressure ulcers (ref.1,2). They have also been shown to decrease forced vital capacity in both the adult and pediatric populations, compromise vascular function and cause a significant amount of pain (ref. 2). These potential complications can lead to worse outcomes for patients and strain patient-provider relationships. Due to the potentially injurious nature of spinal immobilization, judicious use has become the standard recommendation. In 2014, the National Association of EMS Physicians and the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma released a position paper that states that benefits are unproven, saying “Patients may be evaluated on scene to determine whether spinal immobilization is indicated to help prevent unnecessary adverse events” (ref. 6). If there is clinical suspicion for spinal injury, a practitioner should utilize their best judgment in utilizing these tools.

Case Study (continued)

Upon arrival to the ED, both patients are placed into beds in the resuscitation bay. Both patients remain in cervical collars and on rigid backboards.

The driver arrives in no acute distress. Primary survey (ABCDE) shows an awake and alert male, answering questions appropriately and following commands. GCS: 15. BP: 110/72 HR: 67 RR: 16. There are no signs of neurological injury on secondary survey and he has no midline spinal tenderness or deformity. He is log-rolled off the rigid backboard, has no midlinethoracic or lumbar spinal tenderness to palpation or visible deformity. The cervical collar remains in place.

The cyclist is crying in pain. GCS: 15 BP: 120/76 HR: 92 RR: 20. Primary survey shows a well developed female answering questions appropriately and following commands. She denies any other injuries aside from her leg pain. Secondary survey shows bilateral pain and temperature sensation loss over the upper extremities, as well as an obvious closed femur fracture. She denies any spinal tenderness to palpation and no step-offs are noted during log roll so the rigid backboard is removed. She does have pain to palpation of her neck, so the cervical collar is kept in place.

Initial Actions and Primary Survey

When a patient with trauma concerning for spinal injury comes into the Emergency Department, it is important to treat it initially like any other trauma, and focus on the ABCs (Airway, Breathing and Circulation).

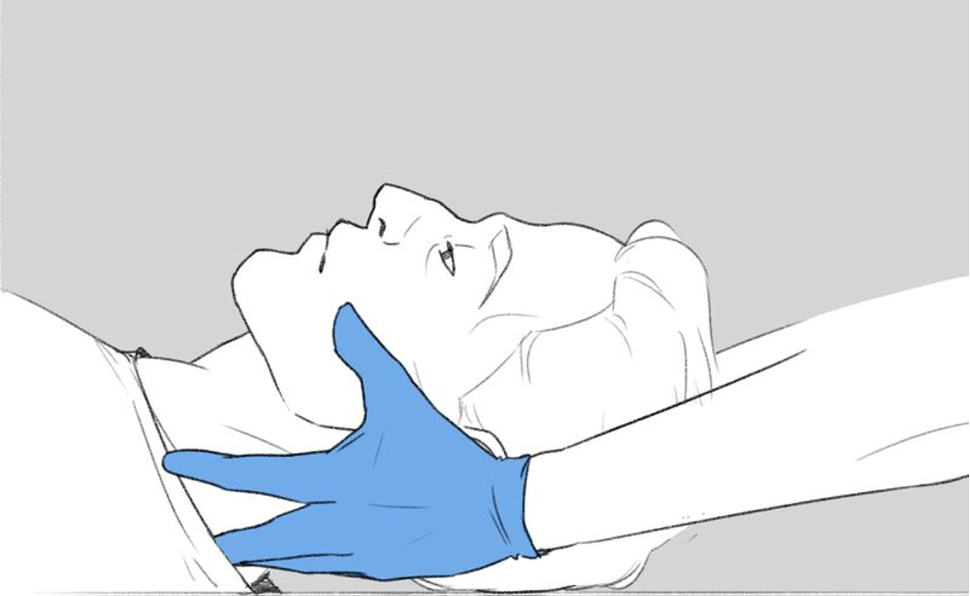

If you are worried about cervical spinal injury, it is important to immobilize the cervical spine if not already immobilized. Until a cervical collar is placed, your hands can stabilize the cervical spine using manual in-line stabilization (Image 3).

Image 3. Manual in-line stabilization of the Cervical Spine. Image courtesy of Catherine Mohr and used under CC-BY-SA-4.0. Original image located at: File:FCEMT supine patient.jpg - Appropedia, the sustainability wiki.

If the patient with suspected cervical spine injury needs to be intubated, it is important to stabilize the cervical spine with manual in-line stabilization as in Image 3. Intubation with a cervical collar in place should not be attempted,

as it can make the intubation prohibitively difficult.

As part of E- Exposure in your primary survey in the trauma patient, it is important that the patient is rolled off the backboard in a manner that maintains immobilization of the cervical and thoracolumbar spine. Below is a good video describing how to logroll a patient off the backboard while maintaining cervical and thoracolumbar immobilization.

Presentation

Patients with spinal fractures and spinal cord injury can come in with a variety of presentations, from a patient with neck plan and paraplegia to a patient with isolated pain in the back/neck with no neuro deficits. It is important to note that for patients who have altered mental status or are unresponsive, their cervical and thoracolumbar spine should be immobilized as they may have spinal fractures or spinal cord injury that is not evident on exam.

Diagnostic Testing

Once a trauma patient arrives in the Emergency Department, the questions often become, “can the C-collar be removed and does this patient need C-spine imaging?”

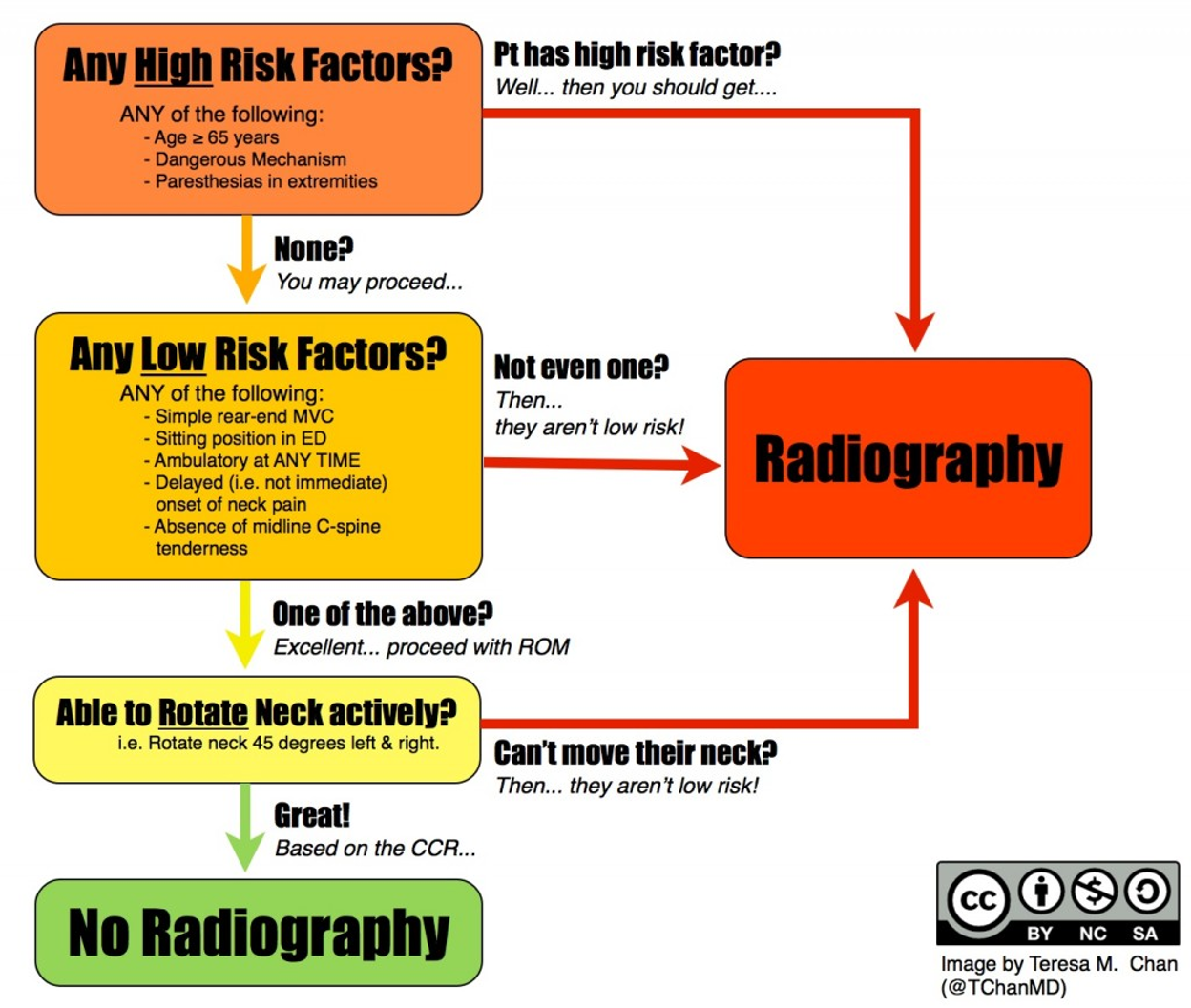

The Canadian C-Spine Rule (CCR) and

National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS) Low-Risk Criteria are clinical decision tools developed to help physicians determine whether cervical spine imaging can be

safely avoided in appropriate patients. With proper implementation of these tools, many patients can safely have their c-spine cleared and their cervical collar removed. Both the Nexus Criteria and the Canadian C-spine Rules are well-validated

decision rules that can be used to safely rule out cervical spine injuries in alert, stable trauma patients without the need to obtain radiographic images (ref.11,12 &13).

NEXUS Criteria

The NEXUS Criteria was a prospective, observational sample of >34,000 patients, aged 1 to 101 years, presenting to 21 US trauma centers. Of those studied, 1.7% had clinically significant cervical spine injuries (CSI). The NEXUS Criteria was found to have sensitivity of 99.6% for ruling out CSI (2/578). This rule also detected 99.0% (8/818) of all CSI (6 of which were injuries that didn’t require stabilization or specialized treatment). Subsequent studies have found a sensitivity of 83-100% for CSI with majority finding 90-100% sensitivity (ref.11). Utilizing this rule could decrease imaging in these patients by as much as 12.6%.

Table 1. NEXUS Criteria for Cervical Spine injury

Below is a video describing the NEXUS Criteria:

Canadian C-spine Rules

The Canadian C-spine Rule (CCR) was a prospective, cohort study that had a convenience sample of almost 9,000 adults who had blunt trauma to the head/neck, stable vital signs and a GCS of 15 (ref. 11). CCR was found to be highly sensitive for CSI, with the majority of studies finding it catches 99-100% of these types of injuries. Subsequent studies have found a sensitivity of 90-100%, which is similar to NEXUS (ref.12). CCR would allow healthcare providers to safely decrease the need for imaging among this patient population by over 40%.

The Canadian C-Spine Rule:

Image 4. Canadian C-spine rules. Please note that dangerous mechanism includes: fall from greater than or equal to 3 feet or 5 stairs, axial load to the head, high speed MVC, motorized recreational vehicle and bicycle collision with an object. This image is courtesy of Teresa Chan, MD and used under the Creative Commons license. Original image located at: Tiny Tip | Canadian C-spine Rule Mnemonic - CanadiEM.

Below is a video with audiovisual depiction of the Canadian C-Spine Rules:

Comparison of NEXUS and Canadian C-spine Rules

In the only trial to undertake a prospective head-to-head comparison of NEXUS to the CCR, the CCR was found to have superior sensitivity (99.4 vs. 90.7).13 While the Canadian C-Spine Rule is more complex and more difficult to memorize than the NEXUS Criteria, it is more sensitive and can potentially be used on patients who cannot be cleared via Nexus Criteria (ref.13).

Unlike the CCR, NEXUS Criteria has no age cut-offs and is theoretically applicable to all patients > 1 year of age (ref.13). There is, however, literature to suggest caution applying NEXUS to patients > 65 years of age, as the sensitivity for these patients may be as low as 66-84%.

If the criteria above are applied, a significant number of patients can be cleared without imaging. All patients with a suspected CSI who cannot be clinically cleared, however, must have radiographic evaluation. This includes patients

with pain, tenderness, a neurologic deficit, altered mental status, a distracting injury, and obtunded patients.

There are no well-validated and utilized decision tools for injuries to the thoracic and lumbar spine. This often leads to a wide variety in practice patterns for practitioners. Often, physicians use a combination of clinical judgment, accident severity and physical examination (midline tenderness, obvious step-off, neurologic examination) to determine if thoracic and lumbar spine imaging is indicated.

Imaging and Follow Up

Computerized tomography (CT) of the cervical spine (CS) has supplanted plain radiography as the primary modality for screening suspected CS injury after trauma (ref.15) Not only is CT CS more accurate than plain radiography, but it is efficient, cost effective, and does not require any additional plain films (ref.15). If a CT CS demonstrates an injury or there is a neurologic deficit referable to a CS injury, a spine consultation should be obtained (ref.8). Cervical spine imaging is discussed further in Cervical Spine Imaging in Trauma.

It is important to note that CT of the cervical spine is great for assessing bony fractures, but can miss ligamentous injury that can cause an unstable cervical spine. Hence, it is important to note that a normal CT scan of the cervical spine does not rule out an unstable cervical spine. Thus, after a negative CT scan, it is important to clinically clear the cervical spine.

For patients who complain of neck pain and have cervical spine tenderness to palpation and are awake, alert, have no neurologic deficits and a negative CT of the cervical spine, there are several treatment options, but limited data (ref.8). This may include continuing the cervical collar until follow up with a spine specialist on an outpatient basis or perhaps additional imaging (often MRI) on an case-by-case basis for possible soft tissue injuries.

Treatment

Any intervention performed on a patient can be considered a “treatment”; this includes utilizing a nasal cannula for oxygen as well as applying a cervical collar or a rigid backboard to a trauma patient. Possible indications and situations

in which spinal immobilization is recommended include:

Table 2. Appropriate use of spinal immobilization in trauma.

Primarily due to situational differences in environment and EMS protocols, many patients are overtriaged and placed in either cervical or spinal immobilization in an attempt to minimize potential traumatic spinal injuries. As a result, it is not uncommon for immobilized patients to be “cleared” from a concerning/devastating spinal injury on arrival to the ED with the use of the previously discussed decision tools.

Knowing the contraindications of spinal immobilization is just as important to knowing when to utilize this treatment. While there are no strict contraindications for spinal immobilization, spinal immobilization is generally not utilized in patients with penetrating trauma to the head, neck or torso without any evidence of spinal injury.

There are multiple risks and benefits to consider when placing someone in spinal immobilization, especially with some of the EDs special populations. To start, both pieces of equipment are known to be quite uncomfortable which can be troubling and distressing for patients at both extremes of age (children and geriatrics) as well as for patients that have a developmental delay. Oftentimes, agitation in patients placed on a backboard can be solved by simply removing the rigid board. Also, differences in the anatomical proportions of children mean that placing a child in both cervical and spinal immobilization often does not lead to a truly neutral spine position. Research in pediatric spinal immobilization is even more sparse than the weak literature available in adults. Current guidelines for pediatric spinal immobilization are driven by NEXUS and Canadian C-spine rules which do not have rigid age components in their scores (ref. 8 & 9).

We have discussed at length the “why,” but as a medical student, you may be asked to place a patient on a backboard or in a cervical collar.

To apply a cervical collar:

Have a partner control movement of the cervical spine by holding manual in-line stabilization throughout the procedure.

Move head into neutral alignment (if needed and not contraindicated).

Measure cervical collar size by placing fingers on the shoulder and record fingers in height to the chin. Adjust the cervical collar to the height of fingers measured.

While manual in-line stabilization is held by a partner, slide the back of the collar underneath the patient’s neck and attach the velcro straps.

Ensure the collar appropriately fits the patient and will limit cervical movement before releasing manual stabilization.

Below is a video that demonstrates how to place a cervical collar:

To place a patient on a rigid backboard:

The patient’s head and shoulders should be grasped by the practitioner who is positioned at the head of the bed, ensuring that the spine is aligned with the head.

An assistant should apply a cervical collar without lifting the head off the bed and the alignment of the spine maintained.

To roll the patient, one or two assistants should place their hands on the opposite side of the patient, positioned at the shoulder, hip and knee.

The individual at the head of the bed should maintain the spinal alignment. When the practitioners are properly positioned and ready to roll the patient, the individual maintaining cervical spine alignment should count to three, at which time the assistant(s) should roll the patient toward themselves. Another assistant should quickly assess the back of the patient before placing the backboard underneath them. When the blackboard is secured, the patient will be rolled back onto the blackboard.

The patient should be positioned at the center of the board while still maintaining cervical alignment.

The practitioner should first secure the upper torso with straps.

The chest, pelvis, and upper legs are secured with straps as well.

The patient’s head should be secured with immobilization devices such as a rolled towel or commercial immobilization foam. A tape is applied to the patient’s forehead to secure them on the backboard.

Ensure that all straps are secured and fastened, re-adjusting as necessary.

Below is a video on how to place someone on a backboard while maintaining spinal precautions:

Pearls and Pitfalls

Many patients that are placed into spinal immobilization can be ruled-out clinically for spinal injury without imaging, utilizing clinical judgment or clinical decision tools (CCR or NEXUS).

Utilizing a C-collar or spinal immobilization is not without risks (ulcers, patient pain).

For patients in whom spinal immobilization is utilized, it should be a priority to remove devices as quickly yet safely as clinically able.

Pediatric research shows decreased utility in spinal immobilization due to anatomical differences and a practitioner should weigh risks and benefits.

C-collars and backboards assume normal morphology of the spine and do not allow for anatomical variances in body shape and type.

Case Study Resolution

The driver was ambulatory in the resuscitation bay and had an unremarkable course. Physical examination was negative for signs of injury and the bedside E-FAST exam was negative. Cervical collar was cleared clinically using NEXUS criteria and he was discharged home by the ED with supportive care as needed.

The cyclist demonstrated both a distracting injury with the obvious long bone fracture as well as clinical signs concerning for a spinal cord injury and spinal precautions were maintained. Imaging ultimately showed an unstable fracture and the patient was diagnosed with central cord syndrome and admitted for further neurosurgical evaluation as well as management of her femur fracture.

References

Theodore N, Hadley MN, Aarabi B, et al. Prehospital Cervical Spinal Immobilization After Trauma: Neurosurgery. 2013; 72:22-34.

Domeier RM. Indications for prehospital spinal immobilization. National Association of EMS Physicians Standards and Clinical Practice Committee. Prehospital Emerg Care Off J Natl Assoc EMS Physicians Natl Assoc State EMS Dir. 1999; 3(3):251-253.

Bauer D, Kowalski R. Effect of spinal immobilization devices on pulmonary function in the healthy, nonsmoking man. Ann Emerg Med. 1988; 17(9):915-918.

Schafermeyer RW, Ribbeck BM, Gaskins J, Thomason S, Harlan M, Attkisson A. Respiratory effects of spinal immobilization in children. Ann Emerg Med. 1991; 20(9):1017-1019.

McHugh TP, Taylor JP. Unnecessary Out-of-hospital Use of Full Spinal Immobilization. Acad Emerg Med. 1998; 5(3):278-280.

EMS spinal precautions and the use of the long backboard. Prehospital Emerg Care Off J Natl Assoc EMS Physicians Natl Assoc State EMS Dir. 2013; 17(3):392-393.

Blunt cervical spine injury in children. Tilt L, Babineau J, Fenster D, Ahmad F, Roskind CG. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2012 Jun; 24(3):301-6

http://www.east.org/education/practice-management-guidelines/cervical-spine- injuries-following-trauma

Anderson RC1, Scaife ER., et. al. Cervical spine clearance after trauma in children. J Neurosurg. 2006 Nov; 105(5 Suppl):361-4.

Foltin G.L., Dayan P., Tunik M., Marr M., Leonard J., Brown K., Hoyle J., and Lerner E.B.; Prehospital Working Group of the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network. (2010). Priorities for pediatric prehospital research. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 26, 773–777

Ian G. Stiell, MD, et. al. The Canadian C-Spine Rule for Radiography in Alert and Stable Trauma Patients. JAMA. 2001; 286(15):1841-1848.

Jerome R. Hoffman, M.D., et. al., for the National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study Group. Validity of a Set of Clinical Criteria to Rule Out Injury to the Cervical Spine in Patients with Blunt Trauma. N Engl J Med 2000; 343:94-99July 13, 2000

Ian G. Stiell, M.D., et.al; The Canadian C-Spine Rule versus the NEXUS Low-Risk Criteria in Patients with Trauma. N Engl J Med 2003; 349:2510-2518December 25, 2003

Pieretti-Vanmarcke, Rafael MD; Velmahos, George C. MD; Clinical Clearance of the Cervical Spine in Blunt Trauma Patients Younger Than 3 Years: A Multi-Center Study of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma. Journal of Trauma-Injury Infection & Critical Care: September 2009 – Volume 67 – Issue 3 – pp 543-550

Lisa Bush, PA-C1; Robert Brookshire, PA-C1; Evaluation of Cervical Spine Clearance by Computed Tomographic Scan Alone in Intoxicated Patients With Blunt Trauma ONLINE FIRSTJAMA Surg. Published online June 15, 2016. Original Investigation | June 15, 2016

Olubode A. Olufajo, MD, MPH, et. al. Does the Computed Tomographic Scan Tell the Whole Story for Cervical Spine Clearance? ONLINE FIRSTJAMA Surg. Published online June 15, 2016. Invited Commentary | June 15, 2016

ATLS Subcommittee; American College of Surgeons’ Committee on Trauma; International ATLS working group. Advanced trauma life support (ATLS®): the tenth edition. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018. ISBN-13: 978-0996826235

Teri Holwerda, APRN-BC. Spinal Fractures: The Three-Column Concept. Spine Universe. May 3, 2017. https://www.spineuniverse.com/conditions/spinal-fractures/spinal-fractures-three-column-concept

Schubert R, Bell D, Gaillard F, et al. Three column concept of spinal fractures. Reference article, Radiopaedia.org (Accessed on 15 Dec 2022) https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-15488

Appendix 1. Stable vs Unstable Spinous Fractures

Most spinal fractures can be classified into two initial types: stable vs unstable. When determining the stability of spinal fractures, we need to consider the three spinal columns. The concept of spinal columns involves dividing the spine into three columns to assess stability.

Table A1. The three columns of the spine.

Image A1. The three columns of the spine. Image courtesy of Matt Skalsi, DC, DABR. Used under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDervis License. Original image located at: Denis three column concept in spinal fracture | Radiology Case | Radiopaedia.org.

Generally, a fracture is considered stable if only the anterior column is involved, as in the case of most wedge fractures. When the anterior and middle columns are involved, the fracture may be considered more unstable. When all three columns

are involved, the fracture is by definition considered unstable, because of the loss of the integrity of the posterior stabilizing ligaments (Ref 18).