Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (AAA) exam

Author Credentials

Authors: Alyssa Alloy MD, FAAEM, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University & Ryan C. Gibbons, MD, FAAEM, FACEP, FAIUM, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University

Update Editor: Sundip Patel, MD, Cooper Medical School of Rowan University (2022 revision).

Original Editor: Matthew Tews, DO, MS, Medical College of Wisconsin

Last Updated: December 2022

Case Study

A 75-year-old male with a past medical history of hypertension presents to the Emergency Department with acute onset of atraumatic abdominal pain radiating to his back. The pain is severe and diffuse. It is associated with nausea and lightheadedness. Social history is significant for smoking 1.5 packs per day of cigarettes for 30 years. Vital Signs are the following: T 98.6, BP 80/50, HR 120. The patient appears uncomfortable and is diaphoretic. His abdomen is distended and diffusely tender to palpation. He has weak distal pedal pulses. The nurse looks over at you, the physician, and asks, “what do you want to do, doc?” You consider your next steps.Objectives

By the end of this module, the student will be able to:

- Understand the emergent nature of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms (AAA)

- Understand the challenge of diagnosing AAA

- Appreciate the anatomy of the abdominal aorta

- Learn the point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) technique to evaluate the aorta

- Understand the challenges and limitations of POCUS

- Appreciate the appropriate ED population at risk for AAA

- Introduce the idea of screening for AAA in an ED population

Introduction

Abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs) are a common clinical entity with a prevalence of 1.3% among middle aged patients, increasing to over 12% among elderly men. (7 & 11) In 2009, there were over 17,000 deaths related to AAAs. (Ref. 10) Mortality rates from ruptured aneurysms remain exceedingly high, between 50-95%. (Ref. 2 & 5)

With each passing minute, the mortality increases by 1%, necessitating timely diagnosis and treatment.18 Up to 30% of ruptured AAAs are initially misdiagnosed, and physical exam alone has a poor sensitivity of less than 65%. (Ref. 1,12,15-16) In fact, only 25% of individuals will present with the classic triad of abdominal pain, hypotension, and a pulsatile mass. (Ref.12 &16)

Early diagnosis through the use of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) has been shown to have a sensitivity of 94-99%. (Ref. 13 & 19) It is safe, effective, and accurate within 4mm compared to CT imaging measurements. (Ref. 4) More importantly, POCUS can reduce mortality by 20-60% in comparison to CT, which in one study took an average of 83 minutes with a mortality above 70%. (Ref. 8 & 17) Furthermore, patients are often too unstable to leave the emergency department to obtain more advanced imaging. Because of these benefits, the use of POCUS has become commonplace in evaluating the patient with a suspected AAA.

Initial Actions and Primary Survey

Patients with a ruptured AAA are typically hemodynamically unstable and require immediate assessment and timely intervention. With any emergent condition, priority remains airway, breathing and circulation. Place all patients on a cardiac monitor and insert two large bore IVs for resuscitation. Perform a focused history and exam while performing a POCUS examination (i.e. RUSH protocol) to narrow your differential diagnosis of hypotension. Consider early consultation of vascular surgery and massive transfusion protocol while expediting angiography by waiving kidney function assessment.

Presentation

The classic triad for patients presenting with a ruptured AAA includes hypotension, abdominal or back pain, and a pulsatile mass. Unruptured AAAs vary in presentation from asymptomatic to nonspecific abdominal, flank, and/or back pain. Patients may experience thrombotic or embolic events as well. Patients with these symptoms and risk factors should receive an aorta POCUS evaluation. Nonetheless, the majority of AAAs are asymptomatic until rupture and are often found incidentally during an evaluation for abdominal pain or during routine screening.

Who to scan

Consider an abdominal aorta ultrasound in the following patients:

- Age greater than 50-years-old with chest, back, flank, abdominal, or groin pain

- Renal colic

- Cardiac arrest

- Hypotension

- Syncope

- Thromboembolic events to the lower extremities

- Neurologic deficit of the lower extremities

Consider AAA screening in asymptomatic individuals

- Recommended for men greater than 65 years of age who ever smoked by American Academy of Family Physicians and US Preventative Survey Task Force6

- Society for Vascular Surgery recommends: (Ref. 9)

- All men age greater than 65

- Men over the age of 55 with family history of AAA

- Women over the age of 65 with family history of AAA or who have smoked

Key Risk Factors to consider (Ref. 3)

- Age greater than 50-years-old

- Male

- Hypertension

- Smoking

- Family history

- Coronary artery disease

- Diabetes

- Hyperlipidemia

- Peripheral artery disease

Point-of-care ultrasound is the initial diagnostic imaging modality for AAA screening, particularly if there is hemodynamic compromise. Remember though, less than 25% of patients will present with the classic triad of abdominal pain, hypotension, and a pulsatile mass.

Anatomy

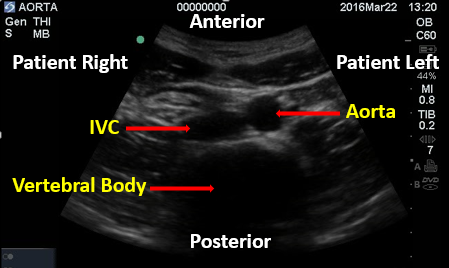

The abdominal aorta is a retroperitoneal vessel entering the abdomen through the aortic hiatus just below the xiphoid process at the level of T12. It lies just anterior to the vertebral body and alongside the inferior vena cava (IVC) as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Aorta and IVC. Image with the permission of Thomas G. Costantino, MD and Ryan C. Gibbons, MD, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University.

It extends to the level of L4 where it bifurcates into the common iliac arteries about 1-2 cm below the umbilicus.

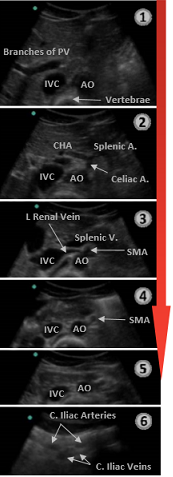

As it descends through the abdomen, the aorta tapers in size moving more superficial and giving off several branches. Sequentially, these are the celiac artery, superior mesenteric artery (SMA), renal followed by the gonadal arteries, and finally the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA).

Figure 2. Descending Aorta and branches. IVF=Inferior Vena Cava; AO=Aorta. Image with the permission of Thomas G. Costantino, MD and Ryan C. Gibbons, MD, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University.

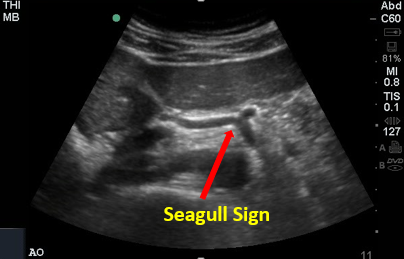

The celiac trunk branches into the common hepatic and splenic arteries (left gastric not visualized) creating the classic “seagull sign’’ seen in the transverse view.

Figure 3. Seagull Sign. Image with the permission of Thomas G. Costantino, MD and Ryan C. Gibbons, MD, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University

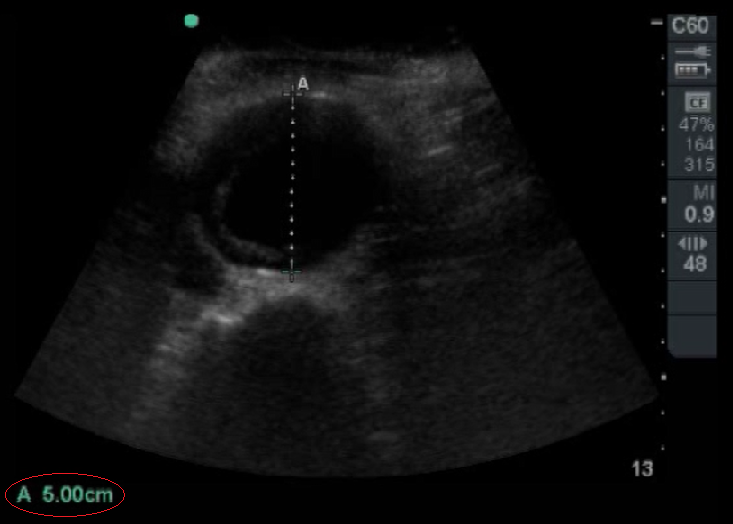

An aneurysm is defined as a focal dilation >50% of a vessel’s normal diameter. A diameter > 3cm delineates an abdominal aortic aneurysm.

Figure 4. Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm that is 5 cm in Diameter. Image with the permission of Thomas G. Costantino, MD and Ryan C. Gibbons, MD, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University.

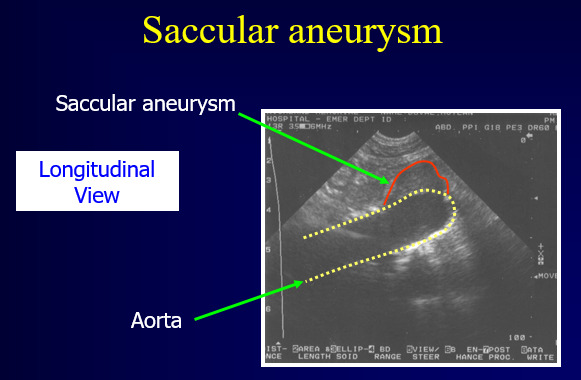

There are two types of AAAs: fusiform (90%) and saccular. Fusiform aneurysms account for the vast majority of AAAs and frequently extend anteriorly and leftward. A saccular aneurysm is a focal outpouching and is occasionally associated with a mycotic source. An aneurysm of the internal iliac artery is typically >1.5 cm.

Figure 5. Fusiform Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. Image with the permission of Thomas G. Costantino, MD and Ryan C. Gibbons, MD, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University.

Figure 6. Saccular Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. Image with the permission of Thomas G. Costantino, MD and Ryan C. Gibbons, MD, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University.

Nearly 90% of AAAs occur infra-renal (Ref.14). The renal arteries are often challenging though to visualize with bedside ultrasound. By scanning to the level of the aortic bifurcation, the provider ensures complete evaluation of the aorta.

Diagnostic Testing

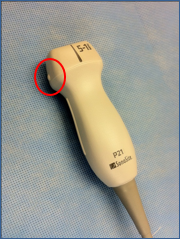

Imaging of the aorta is done in real time. The 2-5 megahertz (mHz) curvilinear abdominal probe is utilized given its superior depth penetration.

Figure 7. Curvilinear Abdominal Probe. Indicator Circled in Red on curvilinear probe. Image with the permission of Thomas G. Costantino, MD and Ryan C. Gibbons, MD, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University.

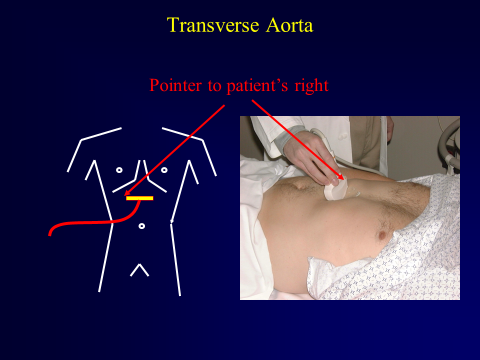

Begin by placing the probe just caudal to the xiphoid process in the transverse orientation with the indicator to the patient’s right.

Figure 8. Curvilinear Abdominal Probe Just Caudal of Xiphoid Process. Image with the permission of Thomas G. Costantino, MD and Ryan C. Gibbons, MD, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University.

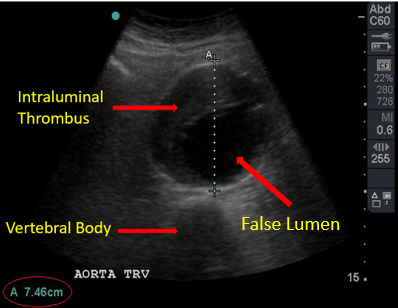

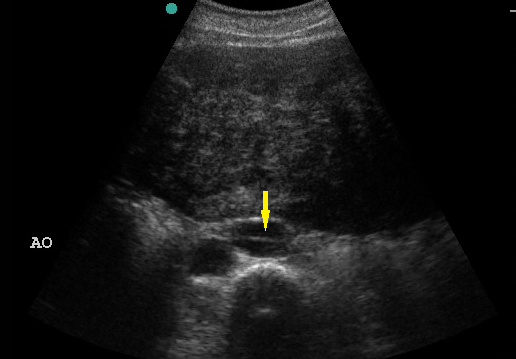

Complete a transverse sweep from the level of the celiac artery to the bifurcation of the aorta. Multiple sequential clips may be needed to visualize the aorta in its entirety. Then, measure the aorta at its maximum diameter in the transverse plane. Be sure to measure the diameter from outer wall to outer wall and to include any thrombus visualized. Thrombus generally appears as echogenic material within the vessel but can be easily missed. Typically, it is located along the anterior and lateral walls and can create the appearance of a false lumen which underestimates the true size of the aneurysm. Be very cautious not to miss these. Measurements are most accurate when the probe is directly perpendicular to the vessel.

Figure 9. Intraluminal Thrombus and Aortic Diameter Measurement of 7.46cm. Image with the permission of Thomas G. Costantino, MD and Ryan C. Gibbons, MD, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University.

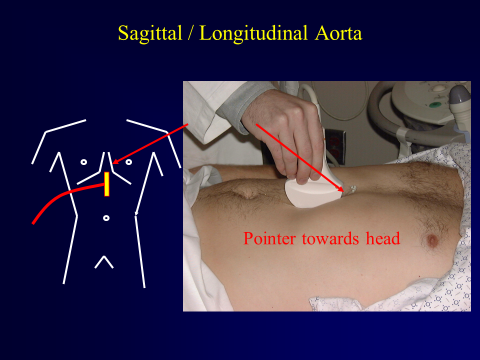

Next, orientate the probe in the sagittal plane with the indicator towards the head of the patient. Again, begin at the level of the celiac artery just distal to the xiphoid process and obtain a clip(s) in the sagittal plane extending as caudally as possible.

Figure 10. Placement of Probe in Sagittal Plane. Image with the permission of Thomas G. Costantino, MD and Ryan C. Gibbons, MD, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University.

Perform a right upper quadrant (RUQ) ultrasound sweep to assess for free fluid when concerned for a ruptured AAA.

Figure 11. RUQ with Free Fluid in Morrison’s Pouch. Image with the permission of Thomas G. Costantino, MD and Ryan C. Gibbons, MD, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University.

Most AAA ruptures though are retroperitoneal (70-90%), which ultrasound is unable to evaluate. (Ref. 21) Nonetheless, one study demonstrated a 97% sensitivity for diagnosing ruptured AAA when combining ultrasound and clinical acumen. (Ref. 20)

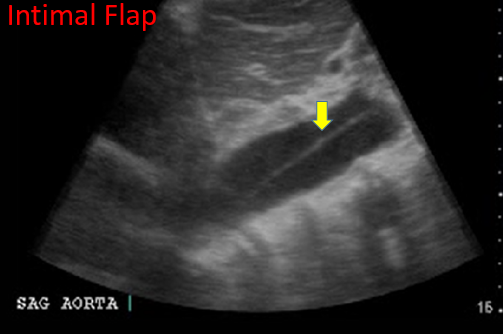

Finally, the presence of an intimal flap is pathognomonic for an aortic dissection. (Aggressive blood pressure control and calling your vascular or thoracic surgeon is warranted immediately).

Figure 12. Intimal Flap. Image with the permission of Thomas G. Costantino, MD and Ryan C. Gibbons, MD, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University.

Technical Considerations

As with any ultrasound study, proper set up is key to obtaining accurate images. The patient should be placed in the supine position at the level of the scanner’s waist. Dim the lights as appropriate and apply adequate ultrasound gel.

The 2-5 mHz curvilinear abdominal probe is best utilized. The 1-5 mHz phased array (cardiac) probe can be utilized as well.

Figure 13. Phased Array (Cardiac) Probe. Circle depicts the Indicator on Phased Array Probe. Image with the permission of Thomas G. Costantino, MD and Ryan C. Gibbons, MD, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University.

The initial depth should be maximized in order to visualize the vertebral body and locate the key landmarks discussed above. Once identified, the depth can be adjusted accordingly to optimize your view. In particular, as you move caudally, the aorta becomes more superficial and less depth is required.

Firm, constant pressure helps displace obstructing bowel. Adjust the gain to limit artifacts. Modifying the angle of the probe or moving slightly off midline while angling back may improve visualization. Establishing a view just caudal to obstructing bowel gas and then sweeping or tilting cephalad may supplement imaging as does the reverse technique. Finally, placing the patient in the left lateral decubitus position may augment imaging as well. Nonetheless, up to 5% of patients will not have a visible aorta. Advanced imaging, including a CT angiography, is then required based on the patient’s hemodynamic stability.

Treatment

All symptomatic AAA regardless of size are considered emergent. Recognize shock immediately and administer fluid and blood products. Early surgical consultation is critical for unstable patients. Ruptured AAAs require immediate surgical repair.

Patients with asymptomatic AAA measuring 3-5 cm (some sources will say up to 5.5 cm) should follow with outpatient vascular surgery outpatient for routine monitoring.

Figure 14. Diagnostic Algorithm Using Point-of-Care Ultrasound.

Pearls & Pitfalls

- 90% of AAAs are infra-renal. Scan the entire aorta to its bifurcation to ensure visualization below the renal arteries.

- Beware the intraluminal thrombus and its false lumen. Remember to include the thrombus to accurately measure the aortic diameter.

- Recognize the pathognomonic intimal flap in an aortic dissection.

Figure 15. Intimal Flap in Aortic Dissection. Image with the permission of Thomas G. Costantino, MD and Ryan C. Gibbons, MD, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University.

The aorta and IVC can be challenging to differentiate. Typically, the thick-walled aorta is the pulsatile, non-compressible, circular structure to the left of the IVC (anatomically and on screen). The thin-walled IVC is the compressible, oval-shaped structure adjacent to the aorta. It may appear to pulsate though due to its proximity to the aorta. If still unsure, use pulsed-wave Doppler to distinguish between the arterial pulsations of the aorta from the venous flow of the IVC, which will only demonstrate mild respirophasic variation.

Figure 16. Pulsed Wave Doppler on IVC and Aorta. Image with the permission of Thomas G. Costantino, MD and Ryan C. Gibbons, MD, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University

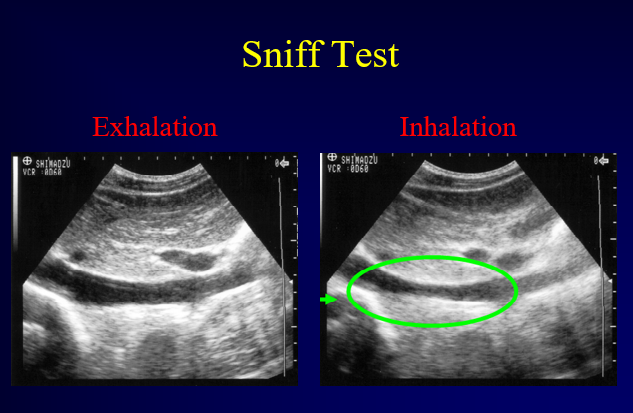

A “sniff test” may help. Have the patient inhale deeply. The negative intrathoracic pressure created by inhalation will increase venous return to the heart causing the IVC to partially collapse.

Figure 17. Sniff Test. Image with the permission of Thomas G. Costantino, MD and Ryan C. Gibbons, MD, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University

Do not forget to perform a RUQ ultrasound sweep to evaluate for free fluid when concerned for a rupture AAA.

Case Study Resolution

The patient received an immediate POCUS which showed free fluid in Morrison’s pouch and an AAA, measuring 10cm, distal to the superior mesenteric artery. The emergency physician consulted vascular surgery immediately and administered packed RBCs and IV fluids. Vascular surgery took the patient for emergency repair. The patient had an uncomplicated hospital course and was discharged home in stable condition with blood pressure and lipid control.

References

- Akkersdijk GJ, van Bockel JH. Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: initial misdiagnosis and the effect on treatment. Eur J Surg. 1998;164:29-34.

- Basnyat PS, Biffin AH, Moseley LG, et al. Mortality from ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm in Wales. British J of Surg. 1999;86(6):765-70.

- Blanchard JF, Armenian HK, Friesen PP. Risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysm: results of a case-control study. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151(6):575-83.

- Costantino TG, Bruno EC, Handly N, et al. Accuracy of emergency medicine ultrasound in the evaluation of abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Emerg Med. 2005;29(4):455-60.

- Ernst CB. Abdominal aortic aneurysm. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1167-72.

- Fleming C, Whitlock EP, Beil TL, et al. Screening for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm: A Best-Evidence Systematic Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:203-11.

- Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): a collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease): endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation. Circulation. 2006;113:e463.

- Hoffman M, Avellone JC, Plecha FR, et al. Operation for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms: a community-wide experience. Surgery. 1982;91:597-602.

- Kent KC, Zwolak RM, Jaff MR, et al. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2004; 39:267-9.

- Kochanek KD, Xu JQ, Murphy SL, et al. Deaths: final data for 2009. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2011; 60(3).

- Lederle FA, Johnson GR, Wilson SE,, et al. Prevalence and associations of abdominal aortic aneurysm detected through screening. Aneurysm Detection and Management (ADAM) Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(6):441-9.

- Lederle FA, Simel DL. Does This Patient Have Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm? The Rational Clinical Exam. JAMA. 1999;281(1):77-82.

- Lindholt JS, Vammen S, Juul S, et al. The validity of ultrasonographic scanning as a screening method for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1999;17:472-5.

- Ma OJ, et al. Emergency Ultrasound. 4th Ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical, 2021.

- Marston WA, Ahlquist R, Johnson G Jr, et al. Misdiagnosis of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 1992;16:17-22.

- Niemann JT. The Accuracy of Physical Examination to Detect Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37(3):366.

- Plummer D, Clinton J, Matthew B. Emergency department ultrasound improves time to diagnosis and survival in ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm [abstract]. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5:417.

- Rahimi SA. Abdominal aortic aneurysm. Available at Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm: Practice Essentials, Background, Anatomy (medscape.com). Accessed on 1 October 2022.

- Rubano E, et al. “Systematic Review: Emergency Department Bedside Ultrasonography for Diagnosing Suspected Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm.” Acad Emerg Med. 2013; 20(2):128-38.

- Shuman WP, Hastrup W, Kohler TR, et al. Suspected leaking abdominal aortic aneurysm: use of sonography in the emergency room. Radiology. 1988;168:117-9.

- Walls R., et al. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier, 2022.

*All images and videos are used with the permission of Thomas G. Costantino, MD and Ryan C. Gibbons, MD, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University