Small Bowel Obstruction

Author Update 2019: Tabitha Ford MD, University of Utah; Megan Fix MD, University of Utah,

Update Editor: Pratiksha Naik, MD

Original author: Megan Fix, MD; University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah

Original edits: David Gordon, MD; Duke University, Durham, North Carolina

Case Study

43-year-old female with history significant for exploratory laparotomy with splenic resection 10 years prior presents with two days of abdominal pain with vomiting. She had two episodes of non-bloody diarrhea three days ago, and has not had a bowel movement in the past two days. She reports passing no flatus during this time. Yesterday, she began having non-bloody emesis, and today, she cannot tolerate any oral intake. On examination, you find an uncomfortable woman who is tachycardic and has a distended abdomen, diffusely tender to palpation without rebound tenderness or guarding.

Objectives

Upon completion of this self-study module, you should be able to:

- List the common causes of a small bowel obstruction.

- Describe the classic presentation and physical examination findings of a small bowel obstruction.

- Discuss the diagnostic modalities available to diagnose a small bowel obstruction.

- Describe the treatment priorities for bowel obstruction.

- Identify which patients are in need of emergent surgical intervention or surgical consultation.

Introduction

Bowel obstruction should be considered as a potential surgical emergency when a patient presents with acute abdominal pain. It occurs when the normal flow of intestinal contents is interrupted. The most common causes are adhesions, followed by tumors and hernias. Other causes include strictures, intussusception, volvulus, Crohn Disease, foreign bodies, and gallstones. Obstruction is classified as small bowel obstruction (SBO) or large bowel obstruction (LBO) based on the level of obstruction. LBO is more commonly caused by malignancy and will not be discussed in detail in this module.

SBO begins when the normal luminal flow of intestinal contents is interrupted and the small intestine proximal to the obstruction dilates. Secretions are prevented from passing distally in a complete SBO. As time progresses, the distension leads to nausea and vomiting and inability to tolerate oral intake. Bacteria may ferment in the proximal intestine and cause feculent emesis. The bowel wall becomes more and more edematous as the process continues and leads to a transudative loss of fluid into the peritoneal cavity. This increases the degree of dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities that are present in these patients. Decreased urine output, tachycardia, azotemia, and hypotension can also be seen.

Bowel obstructions can be defined as partial or complete and simple or strangulated. Partial obstruction is when gas or liquid stool can pass through the point of narrowing, and complete obstruction is when no substance can pass. Partial obstruction is further characterized as high grade or low grade according to the severity of the narrowing, and is often managed conservatively. Complete bowel obstruction has a higher failure rate with conservative therapy, and usually requires operative intervention. Strangulation is the most severe complication of small bowel obstruction and is a surgical emergency. This occurs when bowel wall edema compromises perfusion to the intestine and necrosis ensues. This will eventually lead to perforation, peritonitis and death if not intervened upon.

Initial Actions and Primary Survey

As with all patients, initial concern is for immediate life threats. Assess the airway, determining if copious emesis is causing potential for aspiration. A patient with emesis who is not mentating well may require intubation for airway protection. Vomiting may be controlled with antiemetics and/or nasogastric tube placement. Next, assess the patient’s breathing, applying supplemental oxygen as necessary. In the patient who appears acutely ill with changes in hemodynamics such as tachycardia or hypotension, obtain bilateral intravenous access and administer a bolus of crystalloid fluids as you complete your evaluation.

Presentation

History

The patient with a small bowel obstruction will usually present with abdominal pain, abdominal distension, vomiting, and inability to pass flatus. In a proximal obstruction, nausea and vomiting are more prevalent. Pain is frequently described as crampy and intermittent with a simple obstruction. If the pain becomes more severe, it may indicate the development of strangulation or ischemia. Patients also may complain of diarrhea early in the course of bowel obstruction, with the inability to pass flatus and obstipation occurring after the distal portion of the bowel has emptied (up to 12-24 hours).

A history of prior abdominal surgery is important to ascertain because adhesions are the most common cause of small bowel obstruction. Also important is a history of gastrointestinal disorders such as Crohn disease. A patient who presents with a small bowel obstruction with no history of prior surgery should prompt a search for underlying causes such as tumor or hernia as the cause.

Physical Exam

Physical examination findings include abdominal distension (more prevalent in distal obstructions), hyperactive bowel sounds (early), or hypoactive bowel sounds (late). Fever, tachycardia and peritoneal signs may be associated with strangulation. It is also important to look for possible causes of obstruction such as inguinal hernias, so always include a genitourinary examination. Rectal examination is important as well, because gross blood or hemoccult positive stool may suggest strangulation or malignancy.

Diagnostic Testing

Plain Radiography

Plain radiographs present a convenient diagnostic modality due to low cost and availability. However, these studies are limited by low sensitivity (only 66-85%). In a patient with a concerning abdominal exam, it is reasonable to obtain an upright chest film looking for evidence of perforation suggested by free air (requiring immediate surgical consultation) followed by upright/supine abdominal radiographs.

Findings on plain film that suggest SBO include air-fluid levels in the small bowel or dilated loops of small bowel. The absence of air in the colon or rectum suggests a complete obstruction while the presence of air in the colon suggests a partial obstruction. Plain radiographs can be misleading in difficult cases, and a normal plain film does not rule out SBO.

Small Bowel Series

The diagnosis and degree of small bowel obstruction can be confirmed by a small bowel follow-through or enteroclysis (the duodenum is instilled with air and contrast). These studies used to be considered the gold standard for determining whether an obstruction was partial or complete. More recently, CT has been replacing small bowel follow-through for definitive diagnosis.

Computed Tomography

Computerized tomography has been replacing the small bowel series as the study of choice to differentiate partial versus complete obstruction, to determine the site and cause of obstruction, as well as to identify strangulation early. CT is both sensitive (over 96%) and specific (up to 100%) at diagnosing SBO.

Obstruction is present if the small bowel loop is dilated greater than 2.5 cm in diameter proximal to a distinct transition zone of collapsed bowel less than 1 cm in diameter. A smooth beak indicates simple obstruction without vascular compromise; a serrated beak may indicate strangulation. Bowel wall thickening, pneumatosis, and portal venous gas all suggest strangulation.

CT can also differentiate between the etiologies of SBO; that is, extrinsic causes such as adhesions and hernia from intrinsic causes such as neoplasms or Crohn disease. Furthermore, it has the ability to identify a myriad of other causes of acute abdominal pain such as abscess, hernia, tumor, or inflammation.

When complete bowel obstruction is suspected, oral contrast is often not necessary, and administration may cause excess discomfort for the patient in addition to delays in diagnosis. For patients in which there is a concern for partial SBO, oral contrast may help with diagnosis and can also be therapeutic. Images with intravenous contrast may be added to unenhanced CT to help delineate alternative diagnoses and better demonstrate bowel ischemia if present.

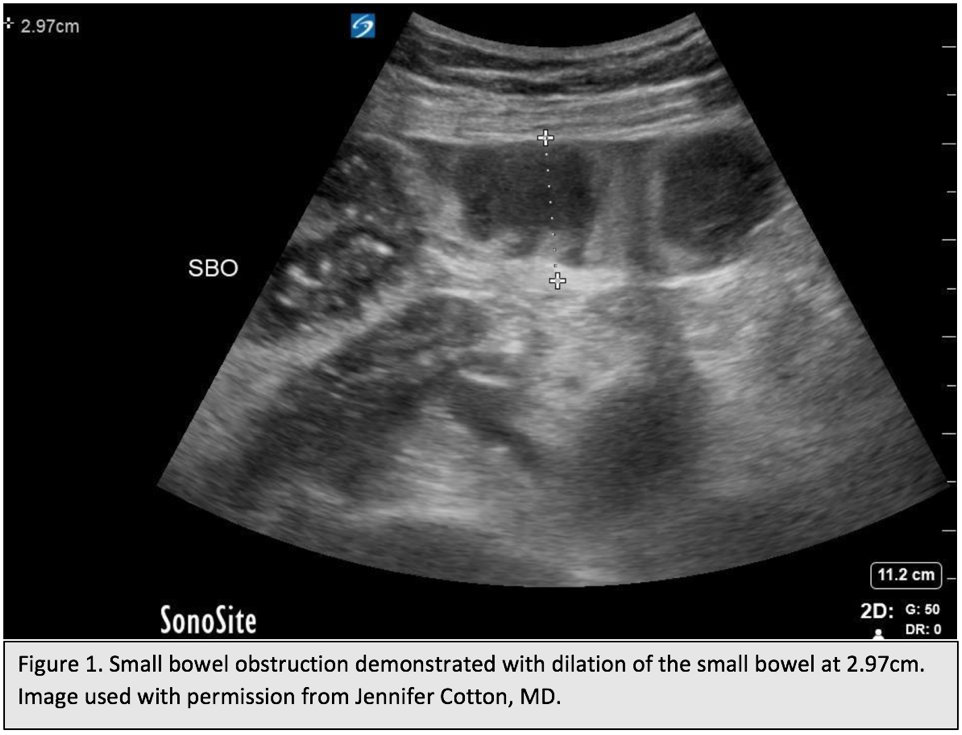

Fig 1. Small bowel obstruction demonstrated with dilation fo the small bowel at 2.97 cm. Original image created by Dr. Jennifer Cotton, MD. Used with permission. Content provided by CC BY-NC-SA. No changes have been made. 2019

Point-of-Care Ultrasound

In the hands of a skilled operator, point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) may be used at the bedside to quickly diagnose SBO while avoiding radiation exposure. Sensitivity ranges from 84-97.7% with 84-100% specificity.

Findings indicating SBO include dilated loops of small bowel (>2.5cm) and whirling or to-and-fro movement of intraluminal contents in the small bowel. Visualization of free fluid between dilated loops of bowel, lack of peristalsis, and bowel wall thickening >3mm suggests the presence SBO complicated by bowel ischemia. As with plain radiographs, normal findings on POCUS do not rule out SBO, and further imaging may be necessary.

FOAMed resources for learning more about POCUS for SBO:

http://www.emdocs.net/us-probe-ultrasound-for-small-bowel-obstruction/

http://www.ultrasoundpodcast.com/2012/10/episode-36-small-bowel-obstruction/

Treatment

Initial management of small bowel obstruction consists of the following goals:

- Resuscitation and electrolyte replacement

- Identifying the severity and cause of the obstruction

- GI decompression

- Symptomatic treatment

- Determining whether or not surgical intervention is indicated

If the patient is acutely ill and/or has peritoneal signs, an emergent surgical consult and aggressive resuscitation should ensue. Crystalloid replacement should start with 2 liters of crystalloid wide open with standard oxygen and monitoring per protocol. If surgical intervention is acutely needed, prophylactic antibiotics may be given.

In the stable patient in whom the diagnosis of SBO is made, it is important to consult with surgery to determine if operative management is warranted. If the patient’s exam or CT scan suggests strangulation (peritonitis, thickened bowel wall, etc.) then operative intervention should ensue. If there are no signs of impending strangulation, then a trial of non-operative management may be appropriate.

Non-operative management consists of GI decompression with a nasogastric tube, intravenous fluid hydration, bowel rest, enteral water-soluble contrast administration, and symptomatic treatment. Frequent reassessment is important to make sure that the patient is not developing signs of strangulation. Intravenous medications for pain control and nausea should be given as needed. The patient should be admitted for observation and serial abdominal examinations. If no improvement is shown, operative management should ensue.

Disposition

- OR: Patients with evidence of strangulation, perforation, bowel ischemia, foreign body obstruction, or failure of conservative therapy should have timely operative exploration and intervention.

- ICU: Patients with severe electrolyte abnormalities or requiring intubation for airway protection should be admitted to the ICU. Occasionally, patients who are very ill will require ICU resuscitation and optimization before operative intervention may be safely performed.

- Floor: Patients who are clinically stable and without complicating features may be monitored on an inpatient basis with a trial of conservative therapy. Studies have demonstrated lower morbidity and mortality in patients admitted to surgical services rather than a medical service. Patients should NOT be discharged home with partial or complete bowel obstruction.

Pearls and Pitfalls

- Prior surgical adhesions are the most common cause of small bowel obstructions.

- Abdominal radiographs may miss small bowel obstruction in up to 25% of cases and should be followed by CT if the diagnosis is not clear.

- If available, ultrasound may be used to diagnose SBO without radiation exposure. Negative ultrasounds should be followed by CT if suspicion remains.

- Strangulation is the most lethal complication of small bowel obstruction and can be present without peritoneal signs on examination.

- Adequate resuscitation, early surgical consultation for impending strangulation, GI decompression, and symptomatic control are the mainstays of therapy.

Case Study

In the patient from the beginning of the chapter, bilateral intravenous access was obtained and a fluid bolus was administered with improvement in tachycardia. Labs were significant for a hypokalemic, hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis, and potassium was repleted. Bedside ultrasound demonstrated fluid-filled loops of small bowel dilated to 2.9 cm with intraluminal hyperechoic material moving back and forth repeatedly. Nasogastric tube was placed and the patient received intravenous maintenance fluids and analgesics. She had no history of SBO and transition point was unclear on ultrasound, so a CT was performed which demonstrated a distal small bowel transition point with evidence of adhesions. She was admitted to the general surgery service, failed conservative management, and was ultimately taken to the operating room, where adhesions were lysed. She had no evidence of strangulated or ischemic bowel, and her post-operative hospital course was unremarkable.

References

Diaz JJ Jr, Bokhari F, Mowery NT, Acosta JA, Block EF, Bromberg WJ, et al. Guidelines for management of small bowel obstruction. J Trauma. Jun 2008;64(6):1651-64.

Cappell MS, Batke M. Mechanical obstruction of the small bowel and colon. Med Clin North Am. May 2008;92(3):575-97, viii.

Bass KN, Jones B, Bulkley GB. Current management of small-bowel obstruction. Adv Surg. 1997;31:1-34.

Horton KM. Small bowel obstruction. Crit Rev Comput Tomogr. 2003;44(3):119-28.

Kahi CJ, Rex DK. Bowel obstruction and pseudo-obstruction. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. Dec 2003;32(4):1229-47.

Tintinalli J, Kelen GD, Stapczynski JS. Intestinal obstruction. In: Tintinalli J, ed. Emergency Medicine Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 6th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2004:523-26.

Long B, Robertson J, Koyfman A. Emergency medicine evaluation and management of small bowel obstruction: Evidence-based recommendations. J. Emerg. Med. 2019;56:2:166-176.