Congestive Heart Failure

Update Author Editor: Christopher Cox MD, Dalhousie University (2019)

Editor: Moises Gallegos MD MPH, Stanford Department of Emergency Medicine,

Author: Amy Pound, MD, University Hospitals Case Medical Center, Case Western Reserve University

Last Update: September, 2019

Case Study

70-year-old female with a history of coronary artery disease, and hypertension presents by ambulance to your emergency department, the morning after Thanksgiving, with progressive shortness of breath. She notes that she has had company all week and as a result she didn’t seek medical care. She has noticed shortness of breath at night and has been resting on at least two pillows. Last night she was unable to sleep and had to stay in her recliner chair until she called the paramedics this morning. She denies chest pain now or at any time this week. She admits that she failed to follow her low salt diet and states she may have missed some of her medications this week due to the holiday.

Her vital signs are HR 105, BP160/80, RR 32, and SpO2 89% on 100% non-rebreather oxygen mask. (case study continues throughout chapter)

Objectives

Upon finishing this module, the student will be able to:

- Discuss the classifications of heart failure.

- Identify the signs/symptoms for acute exacerbation of congestive heart failure.

- Describe how congestive heart failure can be diagnosed based on laboratory, chest x-ray, and Point of Care Ultrasound (PoCUS) studies.

- Prioritize and list ED treatment options for acute exacerbations of congestive heart failure.

Introduction

Congestive Heart Failure (CHF) is one of the most common illnesses treated in the Emergency Department. It affects about 2% of the US population or roughly 4.8 million Americans. In patients over the age of 65, it comprises 20% of hospitalizations, making it the most common admitting diagnosis.

CHF arises when the ventricles fail to maintain forward blood circulation, often when the cardiac demand increases. Precipitating events include cardiac ischemia, dysrhythmias, infection, PE, physical/emotional stress, noncompliance with medication/diet, and volume overload. In this condition, the heart lacks the reserve to compensate for the increased burden within the congested circulatory system.

Classification and Terminology

NYHA CHF Classification

Class I – Ordinary activity not limited by symptoms

Class II – Ordinary activity leads to dyspnea, fatigue, etc

Class III – Marked limitation of ordinary activity

Class IV – Symptoms at rest or with any physical activity

Systolic vs Diastolic Dysfunction

Systolic dysfunction includes a dilated left ventricle with impaired contractility, often caused by ischemia, infarction cardiomyopathy, myocarditis, or dysrhythmias. In diastolic dysfunction the left ventricle remains normal in size, but has an impaired ability to relax. This limits the volume of blood in the ventricle, or preload, and causes increased pressure in the chamber which then reaches the lungs where fluid backs up. One example is infiltrative cardiomyopathy. Diastolic dysfunction has a better prognosis that systolic dysfunction.

High vs Low Output

In low output failure, there is decreased cardiac output secondary to myocardial damage, such as with ischemia, dilated cardiomyopathy, valvular disease, or chronic hypertension. In high output failure, the cardiac output is high or normal, but remains insufficient to supply oxygen demands. High output failure can be found in hyperthyroidism, pregnancy, anemia, AV fistulas, beriberi, or Paget’s disease.

Right vs Left Failure

Right sided failure, or increased pressure and fluid build up in the right ventricle, results in hepatic enlargement, increased jugular venous distention, and dependent peripheral edema of the extremities. Left sided heart failure will cause fluid build up in the left ventricle, resulting in pulmonary congestion.

Initial Actions and Primary Survey

Similar to other patients in the Emergecny Department initial actions include establishing IV access,provding supplimental O2 as needed, and vital sign monitor. These patients may require ECG and CXR

If 100% O2 by non-rebreather fails to increase O2 saturation to at least 95%, noninvasive oxygenation/ventilation (NIPPV) such as CPAP or BiPAP may assist in correcting hypoxia. If there is a failure to improve oxygenation, if the patient cannot tolerate the mask, or has a decline in mental status such that they are unable to protect their airway, then endotracheal intubation is required. The use of NIPPV used early can improve work of breathing as well as oxygenation, however caution should be taken as increased intra-thoracic pressure can reduce preload and worsen hypotension.

Hypotension can be difficult to manage in this patient population secondary to existing fluid overload. Early vasopressor support may be needed. Frequently patients with CHF exacerbation with present with significant hypertension. Nitroglycerin can be a useful medication in helping to reduce preload and reduce progression of pulmonary edema.

Presentation

Typical chief complaints, as in this case, include shortness of breath and peripheral edema.

Case Study, continued

Physical exam:

Your patient is in moderate respiratory distress, sitting forward, and speaking in only three word sentences.

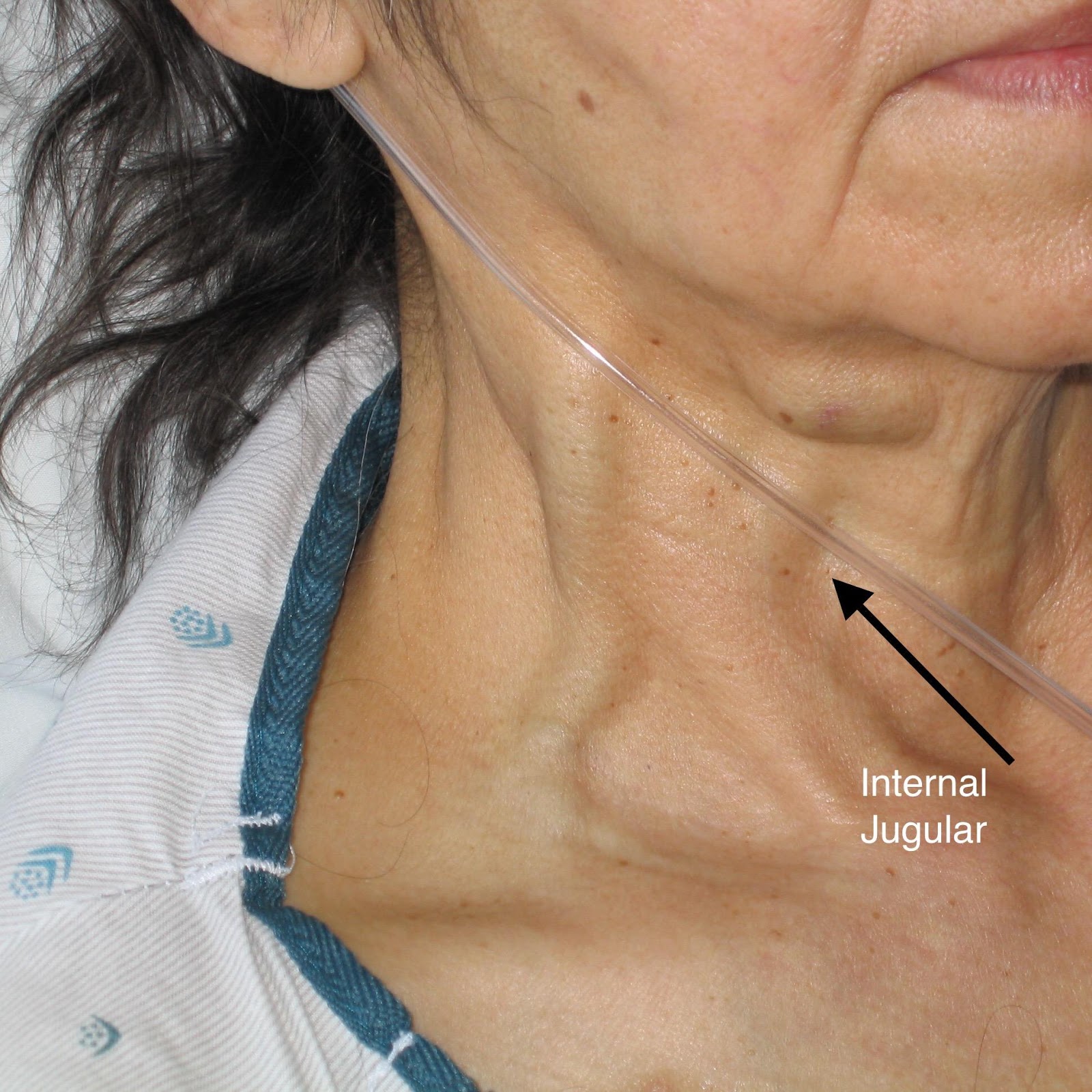

HEENT: She has no stridor. Jugular venous pressure is elevated to the mandible. (Image 1)

Chest: Her lung sounds are crackles in all lung fields without wheezing.

Cardio: She has normal S1and S2. An S3 is present. There is no murmur.

Abdomen: She has no tenderness, no hepato-splenomegaly, and no masses on exam.

Extremities: She has two plus pitting edema to the level of the tibial plateau. (Image 2)

Neuro: She is awake with no weakness, numbness, speech or vision deficits.

Skin: She is pale with central cyanosis, cool to touch, and diaphoretic.

Image 1: JVD is measured by the peak of the pressure wave in the internal jugular vein. You can see this vessel is dilated as it exits medially from under the sternocleidomastoid. See black arrow.

By Ferencga (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons. Notation added by C.Cox 4/2019.

Image 2: Pitting edema

By James Heilman, MD (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

Diagnostic Testing

POINT OF CARE ULTRASOUND: (POCUS)

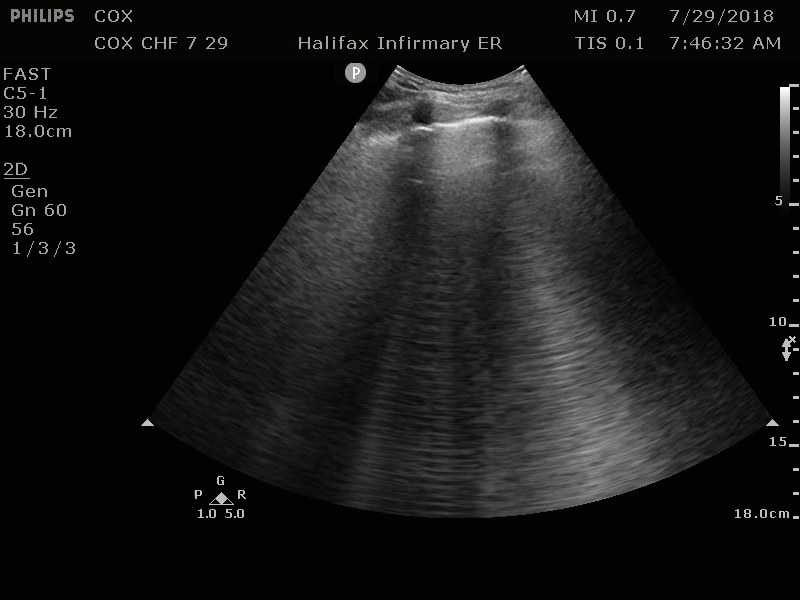

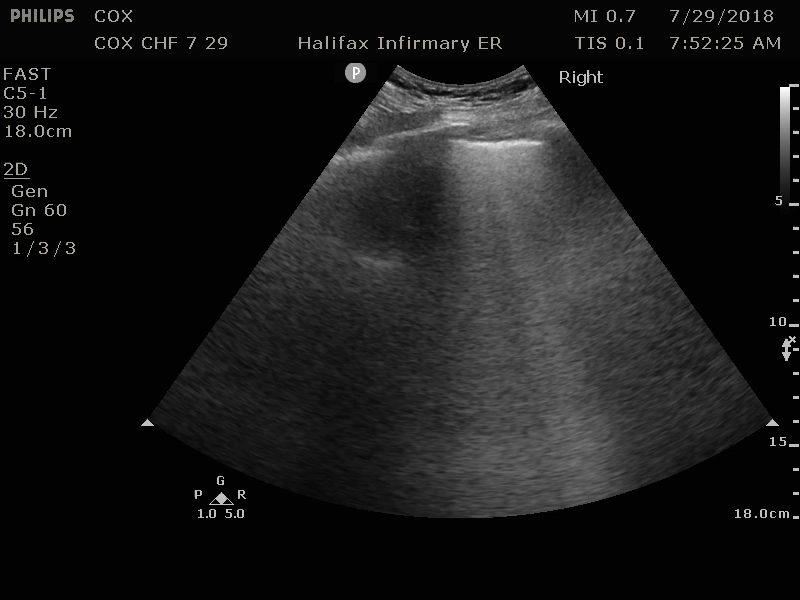

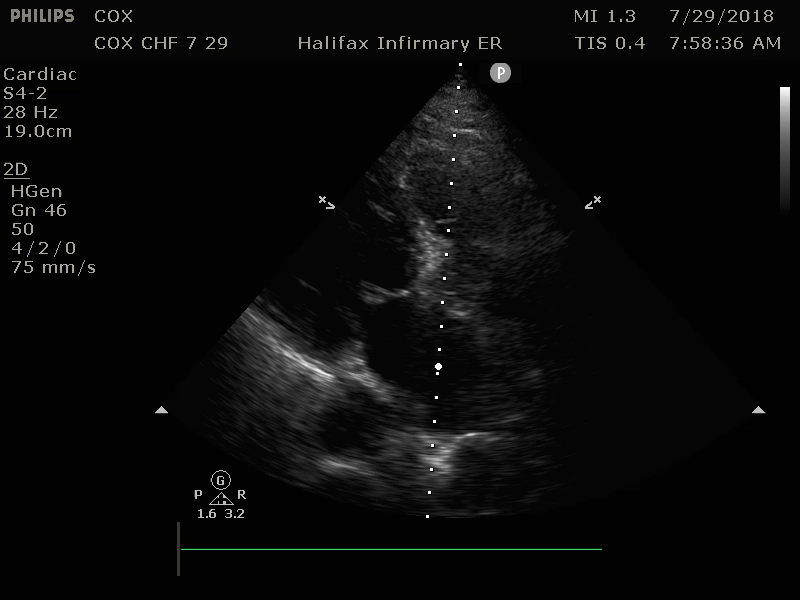

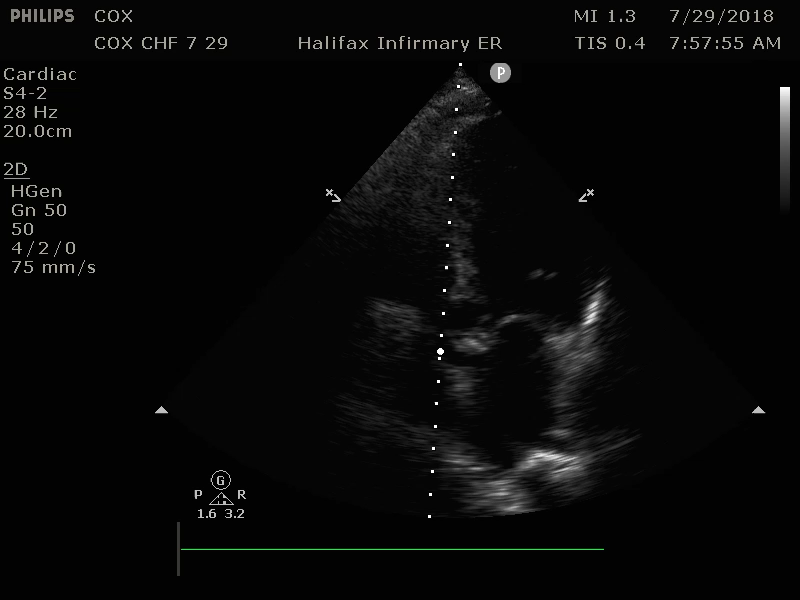

For your patient, your attending physician shows you multiple bilateral lung views, and parasternal long axis (PSL) and apical four chamber (a4C) cardiac views, and explains their significance in making a diagnosis of CHF. (Image 3-6).

Image 3: B-lines in right lung field suggesting interstitial edema. Original contribution by author, C. Cox. CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)

Image 4: B-lines in left lung field suggesting interstitial edema. Original contribution by author, C. Cox. CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0

Image 5: PSL, Dilated Left Ventricle with poor contraction and poor mitral valve excursion suggesting diminished Ejection Fraction (EF) Original contribution by author, C. Cox. CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0

Image 6: a4C, Dilated Left Ventricle with poor contraction and Mitral valve with poor excursion suggesting diminished EF Original contribution by author, C. Cox. CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)

Your attending states that your patient has qualitatively diminished heart function and bilateral interstitial edema. As demonstrated at the bedside, she has B-lines in greater that 2 thoracic quadrants bilaterally which suggests a cardiac source of pulmonary edema. (Sensitivity 97%, Specificity 95%)

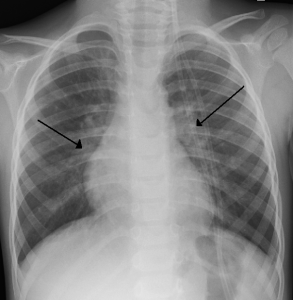

CXR

Common findings are cardiomegaly and effusions. Chest x-ray (CXR) findings may lag by 12 hours from onset of symptoms, and subsequently CXR findings may persist for several days despite clinical improvement. 1 out of 5 patients admitted for CHF exacerbations showed lack of any pulmonary congestion on CXR.

Cardiomegaly is defined as a cardiothoracic ratio greater than 50% diameter. Patients with diastolic failure may have normal heart size.

Image 7: By Nevit Dilmen (Own work) [GFDL](http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

Additional CXR findings include:

- Peribronchial cuffing – thickened bronchial walls secondary to edema. Indicated by arrow in above image.

- Perihilar congestion – large hila with indistinct margins suggest pulmonary vasculature edema. Indicated by the two arrows in the image below.

Image 8: By James Heilman, MD (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

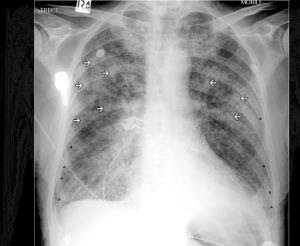

- Cephalization – redistribution of blood flow to upper lobes. Only seen on upright films. Circled area in the image below.

Image 9: By James Heilman, MD (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

- Pleural effusion – meniscus at the angle of the diaphragm. Arrow in above image.

- Kerley B lines – Dilated lymphatic channels. Typically 2 cm in length and horizontal, peripherally located perpendicular to pleura. Black arrowheads in following image are kerley b lines, white arrows are septal lines

Image 10: http://www.radpod.org/2007/03/02/acute-pulmonary-oedema/Reference: Chapman S, Nakielny R. Aids to Radiological Differential Diagnosis 4th edition. Saunders 2003

Credit: Dr Laughlin Dawes

- Alveolar edema – batwing appearance

BNP

The Breathing Not Properly study found BNP (brain natriuretic protein) to be 90% sensitive and 76% specific for the diagnosis of CHF. Release is stimulated by high ventricular filling pressures. It has a diuretic effect, and antihypertensive effect, by increasing the amount of sodium excreted in the urine.

- <100pg/ml: unlikely CHF

- 100-500pg/ml: potentially CHF, although could also be PE, pulmonary HTN, ESRD, cirrhosis, or hormone replacement therapy

- >500pg/ml: most likely CHF

BNP levels may be most useful in tracking acute disease severity when compared to previously known levels. BNP levels may not always correlate with suspicion for CHF exacerbation, however, and clinical judgment should be used to further evaluate these patients.

Other Laboratories

- CBC to check for anemia

- Electrolytes: Na, K, Mg for abnormalities due to fluid overload or renal insufficiency

- Creatinine to check for renal dysfunction

- Troponin I or T to check for acute ischemic event.

ECG

May show underlying cardiac ischemia, dysrhythmias, LVH or heart block. A normal ECG has a high negative predictive value for systolic dysfunction.

Echocardiogram with Ejection Fraction

Normal ejection fraction is 55-75%. Patients with severe CHF may have EF less than 20%. Echocardiogram can also be used to visualize ventricular size and any wall abnormalities or valvular pathology, pericardial thickening, tamponade or constrictive pericarditis as additional contributors to CHF.

Treatment

ED Treatment

In addition to initial actions noted above, treatment depends upon clinical presentation.

Normotensive patients: First give rapid acting nitrates to vasodilate and reduce afterload. These may be given sublingual, IV, or transdermal as nitroglycerin tabs/spray, push/gtt, paste/patch respectively. IV Morphine can be given for chest pain and anxiety, and may increase vasodilation. IV diuretics, such as furosemide, can increase urine output, lessening fluid overload, and may also contribute to vasodilatory effects.

Hypertensive patients: If high dose nitrates fail to control the blood pressure, some experts suggest adding Nitroprusside IV drip for severe, persistent hypertension. Nitroglycerin will have more effect as a venous dilator than arterial dilator. Nitroprusside is a more balanced venous and arterial dilator.

Hypotensive patients: Avoid nitrates, furosemide, and morphine, as they will drop the blood pressure. BiPAP may have similar adverse effect due to decreased preload as intra-thoracic pressure rises. Increased myocardial contractility with norepinephrine, dopamine, dobutamine, amrinone or milrinone may improve vital sign parameters so that some of the other therapies may be used.

Severe or Chronic low output CHF: Patients may be on ACE inhibitors or ARB to increase hemodynamic stability and exercise capability. If blood pressure allows, consider continuing this medication. If not already on ACEi or ARB, evidence does not support use in acute exacerbations.

Surgical Therapies

As a patient’s CHF becomes more advanced, they may need an Automatic Internal Cardiac Defibrillator (AICD), Left Ventricular Assistance Device (LVAD), or heart transplant.

AICD placement

MADIT trial showed that in patients with previous MI, EF < 35%, non-sustained ventricular tachycardia, and inducible ventricular tachycardia unresponsive to procainamide, AICD placement reduced sudden death by 54% at 2 yrs.

MADIT II trial showed that patients with history of MI and EF <30% had a 29% reduction in mortality after AICD placement.

LVAD placement

Patients may receive an LVAD as a temporizing measure until a heart transplant can be performed, or as a definitive treatment alone, if not a transplant candidate. The REMATCH study showed that patients had increased quality of life and had a 52% rate of survival at one year, compared to 25% for medical management only.

Heart transplant

Heart transplant is the only long-term definitive treatment for congestive heart failure. Patients who receive a heart transplant have a 10-year survival rate of 50%.

Pearls and Pitfalls

- Acute exacerbations of CHF can rapidly progress over hours to days, commonly due to a precipitating event, leaving the patient with no reserve to compensate for increased burden on the heart.

- The precipitating event may be an MI! Check an ECG and troponins.

- CXR findings may lag by 12 hrs. Treat clinical symptoms, and use PoCUS of the heart and lungs if available.

- Most common CXR findings are cardiomegaly and effusions.

- Start with 100% O2 on NRB mask, but use noninvasive CPAP or BiPAP early for increased work of breathing, or intubate when necessary.

- Elevating the head of bed will reduce venous return and decrease preload and improve patient symptoms. In a small group of stable patients who are cognitively intact, placing the legs over the side of the bed may also be helpful in achieving the same physiologic outcomes mentioned previously.

- AVOID nitrates, morphine, and diuretics in hypotensive patients, and be careful with BiPAP these interventions may have a negative effect on blood pressure.

- Patients who present with new heart failure will require thorough inpatient workup to determine if it is a result of ischemic or non-ischemic disease.

Case Study, conclusion

Your patient was started on BiPAP, received three nitro sprays sublingually, and a nitroglycerin drip was started at 4ug/min IV and was titrated to a systolic blood pressure of 130 mm Hg. She received furosemide 40mg IV and the nurses documented a diuresis of 1500 ml of urine in the next two hours. Her troponin I was normal range, as was her CBC, and CHEM 7. Her BNP was elevated to 1020 pg/ml. She was monitored on a cardiac monitor until she was transferred to the hospital cardiac step down unit where she was weaned off of BiPAP, transitioned to oral furosemide, had her low salt diet reinstated, and was transferred to a general floor bed. She was discharged on hospital day 4 on furosemide, an ACE inhibitor, a low salt diet, and outpatient follow up with her primary care provider in one week.

References

- American Heart Association. Classes of heart failure. Available at: http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/HeartFailure/AboutHeartFailure/Classes-of-Heart-Failure_UCM_306328_Article.jsp. Accessed: Mar 16, 2016.

- Collins, S.P., Storrow, A.B. Chapter 53: Acute Heart Failure. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 8e. Online@ Access Medicine. McGraw-Hill Medical

- PMID: 12135939, McCullough PA, Nowak RM, McCord J, et al: B-type natriuretic peptide and clinical judgment in emergency diagnosis of heart failure: analysis from Breathing Not Properly (BNP) Multinational Study. Circulation. Jul 23 2002;106(4):416-22.

- PMID: 16234501, Wang CS, FitzGerald JM, Schulzer M, et al: Does this dyspneic patient in the emergency department have congestive heart failure?. JAMA 2005; 294:1944.

- PMID: 18614781, Gray, A, Goodacre, S, et al. Noninvasive ventilationin acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema. N Engl J Med 2008; 359: 142-151.

- PMID: 8960472, Moss AJ, Hall WJ, Cannom DS, et: Improved survival with an implanted defibrillator in patients with coronary disease at high risk for ventricular arrhythmia. Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial Investigators. N Engl J Med 1996; 335:1933.

- PMID: 11794191, Rose EA, Gelijns AC, Moskowitz AJ, et al: Long-Term Use of a Left Ventricular Assist Device for End-Stage Heart Failure. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:1435-1443.

- PMID: 16387212, Collins SP, Lindsell CJ, Storrow AB et al: Prevalence of negative chest radiography results in the emergency department patient with decompensated heart failure. Ann Emerg Med. Jan 2006;47(1):13-8.

- PMID: 11911755, Publication Committee for the VMAC Investigators : Intravenous nesiritide vs nitroglycerin for treatment of decompensated congestive heart failure: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002; 287:1531.

- PMID: 18403664, Lichtenstein,D. Meziere, G. Relevance of Lung Ultrasound in the diagnosis of respiratory failure. Chest, 134 (1) (2008), pp. 117-125.

- PMID: 8376698, Ho KK, Pinsky JL, Kannel WB, Levy D. The epidemiology of heart failure: the Framingham Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993 Oct. 22(4 Suppl A):6A-13A.

- PMID: 30266198, Long B, Koyfman A, Gottlieb M. Management of Heart Failure in the Emergency Department Setting: An Evidence-Based Review of the Literature. J Emerg Med, 55(5), 2018, 635-646.Congestive Heart Failure (CHF)