Airway

Author Credentials

Written by: Joshua Walker, MD, FACEP / University of Central Florida

Editor: Sarkis Kouyoumjian, MD / Wayne State University

Section Editor: Matthew Tews, DO / Indiana University School of Medicine

Update: 2023

Case Study

You are working at an emergency department when you get a call on the EMS radio of a patient coming emergently to you via EMS with respiratory distress. They have a 70-year-old male who called for shortness of breath. They have tried and failed positive pressure ventilation enroute. They are now bagging the patient. They will arrive in five minutes. How would you prepare?

Objectives

By the end of this module, the student will be able to:

- Understand causes of airway compromise and which interventions may be helpful.

- Describe the adjunct tools that support airway patency in a compromised patient.

- Understand and describe rapid sequence intubation.

- Describe the indications and equipment for direct and video laryngoscopy.

- Understand proper confirmation of an airway.

Introduction

The airway is one of the most important skills to become competent at managing in emergency medicine. Nothing else that an emergency physician encounters has quite the impact on morbidity and mortality. This should be part of the initial evaluation and management of every emergency department patient. Initially on evaluation of any patient the patency, protection, and functionality of the airway should be assessed. Patency relates to the anatomy of the airway from the pharynx to the lungs. Failures in this area can include trauma (facial fractures, tracheal injury, obstruction), allergy (angioedema of the tongue or pharynx), or any other disease process which prevents or impedes airflow through the respiratory tract. Failure to protect the airway would be related to higher order disease processes that affect the patient’s mental status, such as intracranial hemorrhage, seizures, or shock. When a patient’s airway is not patent or protected, the emergency physician must intervene to prevent any further decompensation. This can be one of the most satisfying and life-saving procedures in emergency medicine but can also be one of the most challenging and life-threatening procedures should failure occur.

Preparation

One of the first steps when coming onto shift should be to go to your resuscitation area(s) prior to shift to ensure that all the necessary respiratory supplies are stocked and ready to be accessed should they be needed. Then, during a shift, once it is deemed that an intubation procedure is going to be necessary there should be an automatic checklist of things needed prior to patient arrival or to be ready almost immediately should the need arise.

Supplies to Prepare Ahead of Procedure

Bag valve mask

Suction canister with tubing and Yankauer suction

Plan to have two or more in case there is obstruction of the suction device due to airway debris such as vomitus or blood, or voluminous materials required use of both. This can severely impede your view and chances of success.

Laryngoscope

Direct: Standard MAC, Miller, etc.

Video: Glidescope, CMAC, etc.

Endotracheal tubes

Preferable to have a variety of sizes in case of failure to pass

Adult male usually 7.5-8.0

Adult female usually 7.0-7.5

Pediatric – Safest to refer to Broselow tape

cuffed tube = (Age/4)+3

uncuffed tube = (Age/4)+4

Cricothyrotomy usually 5.0-6.0 (see below)

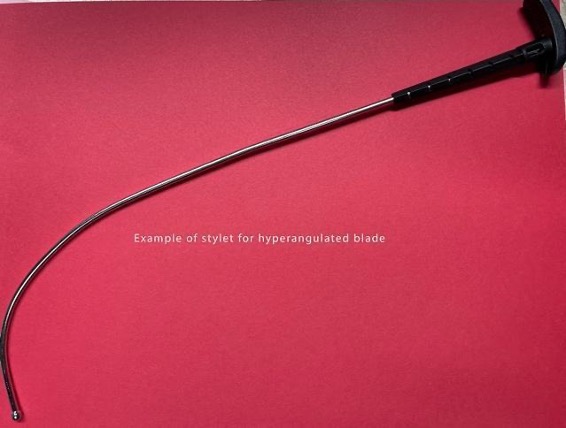

Stylet

Standard stylet for standard intubation

Rigid stylet for hyperangulated blades of video laryngoscope

Rescue Devices

Extraglottic devices

Examples include LMA and I-gel devices

Elastic gum bougie

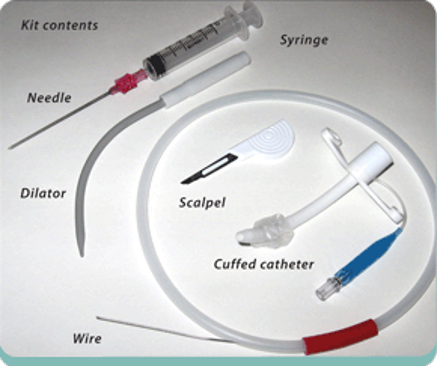

Surgical Airway Supplies

Commercially available cricothyrotomy kit (i.e. Melker kit)

Seldinger technique

Scalpel with endotracheal tubes (5-0 or 6-0) and trach hook

Pre-oxygenation

In order to help prevent hypoxia during intubation attempt, pre-oxygenation with a non-rebreather or high flow nasal cannula can be helpful if time permits. This is a simple and easy intervention, which is as simple as placing a non-rebreather or nasal cannula. This will help to wash out the lungs of nitrogen and give a significant advantage of increased apneic time prior to hypoxia. Another potential way to achieve this is a trial of non-invasive ventilation (BiPAP or CPAP) to assist in a delayed sequence to help prevent hypoxia and attempt at optimization prior to intubation attempt.

Physiologic considerations

There should be heavy consideration to optimization of hemodynamics prior to intubation attempt if possible. Those patients who are hypotensive prior to intubation are likely to have further compromise when intubation medications are given. Consider IV infusion vasopressors or push dose vasopressors. Norepinephrine is generally common and most preferred in this setting. Patients who are significantly acidotic prior to intubation attempt are at high likelihood of complications. Acidosis should be correct as much as possible prior to intubation. Also, it is important to remember that those patients relying on their sympathetic drive (i.e. trauma patients) may have significant decompensation once paralytics and sedatives are pushed.

Predicting which patients will be anatomically difficult

LEMON

Look – First step is to determine if the airway will be difficult due to body habitus, obstructions, etc.

Evaluation 3-3-2 rule – 2 fingerbreadths of mouth opening, 3 fingerbreadths thyromental distance, and 2 fingerbreadths mandible to the thyroid notch

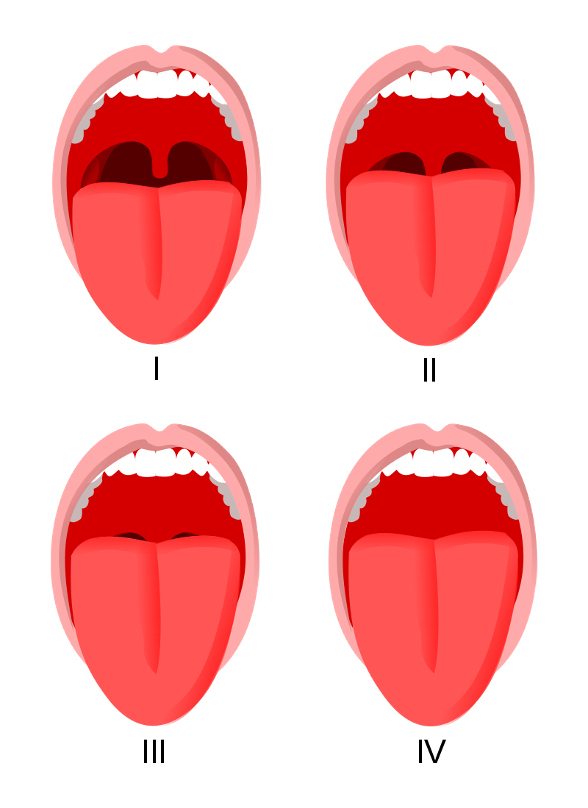

Mallampati:

Class I – Uvula, soft palate, and pillars visible

Class II – Uvula partially blocked by tongue

Class III – Soft palate visualized

Class IV – Soft palate is not visible at all

Figure 1. Mallampati Score. Courtesy of JMarchn. Used under Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike Unported license. Original website: Mallampati Score - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf (nih.gov).

Figure 1. Mallampati Score. Courtesy of JMarchn. Used under Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike Unported license. Original website: Mallampati Score - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf (nih.gov).

Obesity / Obstruction- Should assess for any foreign body obstruction

Neck mobility - patients with trauma, the elderly or medical conditions like Down’s syndrome and rheumatologic conditions.

Intubation

Rapid Sequence Intubation – RSI

Consideration to the following medications and dosages. In general, the emergency physician should know these medications and dosing very well as well and the contraindications to each of those medications.

Induction agents

Etomidate

0.3 mg/kg intravenously

Theoretical risk of adrenal suppression with this medication

Ketamine

1-2 mg/kg intravenously

Propofol

1-2 mg/kg intravenously

Table 1. Common sedative agents in rapid sequence intubation.

Paralytic agents

The paralytic of choice is user dependent and there is no data to suggest superiority of one versus the other.

Succinylcholine

1-1.5 mg/kg intravenously

Caution in those patients with renal failure or known hyperkalemia

Caution in burns greater than 24 hours

Caution in patient with rhabdomyolysis

Shorter duration of action 5-10 minutes

Onset time is ~45 seconds

Rocuronium

0.6-1.5 mg/kg intravenously

Longer duration of action

Duration 40-60 minutes

Onset ~60-75 seconds

Table 2. Common paralytic agents used in rapid sequence intubation.

Airway Maneuvers

The first effort to improve airway patency should be re-positioning of the head and jaw in an attempt to relieve posterior airway obstruction. These simple maneuvers are described below.

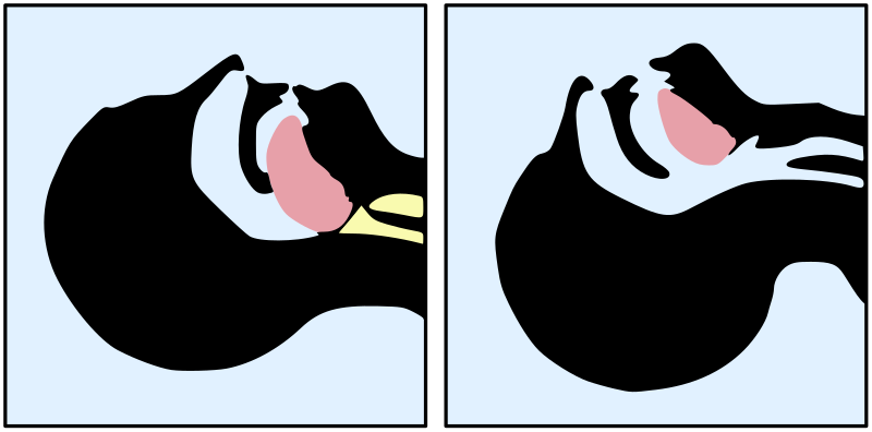

Head-Tilt Chin-Lift

Head-Tilt Chin-Lift Maneuver to open an obstructed airway

This basic maneuver should only be attempted on patients who do not have any clinical suspicion of cervical spine trauma. With one hand, the clinician levers the patient’s head by placing pressure over the forehead, angling the head superiorly. The index and middle fingers of the other hand place upward pressure on the mandible, which serves to lift the tongue off the posterior pharynx. This maneuver is most effective at relieving airway obstruction from the tongue against the posterior pharynx.

Figure 2a. Head-Tilt Chin-Lift Maneuver to open an obstructed airway. Image courtesy of Vassia Atanassova and Offnfopt. Original image located at: File:Tongue blocking airway.svg - Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 2a. Head-Tilt Chin-Lift Maneuver to open an obstructed airway. Image courtesy of Vassia Atanassova and Offnfopt. Original image located at: File:Tongue blocking airway.svg - Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 2b. Head-tilt chin-lift. Image courtesy of Navdeep Sekhon, MD. Image used with permission.

Figure 2b. Head-tilt chin-lift. Image courtesy of Navdeep Sekhon, MD. Image used with permission.

Jaw Thrust

This maneuver would be the favored airway technique in a patient who has any suspicion of cervical spine injury. The provider uses 2 hands to place the pads of their fingers posterior to the angles of the mandible bilaterally and lifts or pulls the mandible anteriorly.

Figure 3. Jaw Thrust maneuver to create a patent airway in patients with suspected cervical spine injury. Image courtesy of Brandon Lopez R.N. and Navdeep Sekhon, MD. Used with permission.

Figure 3. Jaw Thrust maneuver to create a patent airway in patients with suspected cervical spine injury. Image courtesy of Brandon Lopez R.N. and Navdeep Sekhon, MD. Used with permission.

This should lift the tongue off the posterior pharynx, as well as moving it anteriorly in the oropharynx.

Airway adjuncts

Oropharyngeal airway

Can be used in patients who have no gag reflex. Generally, only used in those who are unconscious. It can also be used as a bite-block in intubated patients. Either of the aforementioned

maneuvers can be augmented by the use of airway adjuncts, such as oropharyngeal (OPA) or nasopharyngeal (NPA) airways. The oropharyngeal airway is a small, curved piece of plastic, shaped like a hook that is placed over the tongue

inside the mouth. The OPA pulls the tongue forward and maintains the tongue position away from the posterior pharynx. OPAs should only be used in unconscious patients, as it may cause nausea or vomiting in a patient with

an intact gag reflex.

Figure 4. Oropharyngeal airways. Image Courtesy of Joshua Walker, MD, University of Central Florida.

Nasopharyngeal Airway

A softer airway inserted through the nose which can be used in conscious patients who are having trouble maintaining their airway. The nasopharyngeal airway is a softer, longer tube of plastic

that is inserted into the nare, extending into the posterior pharynx. Clinicians must lubricate the NPA prior to insertion with a water-soluble lubricant or anesthetic jelly. Unlike an OPA, a NPA may be used on a conscious or

semiconscious patient. Care should be taken to minimize trauma to the nasal passage, as epistaxis is a common side effect of this procedure. NPAs are contraindicated in patients with facial trauma involving the nose or central

face.

Figure 5. Nasopharyngeal Airways. Image Courtesy of Joshua Walker, MD, University of Central Florida.

Below is an excellent video describing how to insert an oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal airway.

Technique

Consideration of the Seven P’s of RSI

Preparation

Obtain supplies

Get needed help – Nursing, respiratory therapy, etc.

Preoxygenate

Non-rebreather or high flow nasal cannula

Bipap or cpap

Pre-intubation physiologic optimization

Hemodynamic consideration of decompensation

Vasopressors or fluid boluses as needed

Paralysis

Consider paralytic of choice and dose

Positioning

Final positioning. Ear to sternal notch. Head of bed lowered to an appropriate level. Keep the airway open until intubation is completed.

Placement

Goal is first-pass success to prevent hypoxia and/or aspiration.

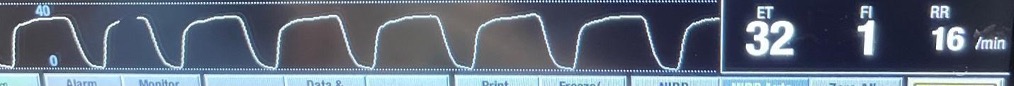

Confirmation with capnography.

Post-intubation management

Provide lung-protective volumes

Hemodynamic management

Adequate sedation and analgesia

Below is an excellent video describing how to prepare for an intubation attempt:

Patient positioning

One of the most important aspects of the procedure is to place the patient at a level that is comfortable for the medical provider performing the intubation. Positioning of the patient helps to maximize the chances of a successful intubation attempt. One goal of positioning is to alight the visual axis of the larynx to help maximize glottis exposure while protecting the patient from aspiration events during intubation attempt. Two common positioning recommendations are recommended:

Sniffing position – the c-spine is flexed with elevation of the head until the ear is at the level of the sternal notch.

Ramped position – both the torso and the head are elevated to > 20 degrees. Helpful in patients with obesity.

There has been no data that either approach is clinically superior in the emergency department setting. Neck extension may be contraindicated in those at risk for cervical instability. This includes the elderly population, trauma patients, patients with Down’s syndrome, and those with rheumatologic conditions.

Direct laryngoscopy

This technique utilizes the Miller (straight) and MAC (curved) blades. This is a mainstay for the emergency physician. The operator stands at the head of the bed and places the patient into the sniffing position or the head-tilt chin-lift maneuver (except for patients with suspected cervical spine injury). Hold the laryngoscope in the left hand and once the patient is adequately paralyzed, the operator should open the patient’s mouth with their right hand and remove any dentures or removable dental hardware. The mouth should be held open with the right hand, in a scissoring motion with the thumb and forefinger to spread the teeth apart. The laryngoscope blade is inserted using the left hand at the right side of the tongue, sweeping the tongue superiorly and medially as gentle upward force is being placed on the mandible. Depending on the type of blade used, the operator will either place the blade in the vallecula (MAC) (the recess between the base of the tongue and the folds of the throat) or directly on top of the epiglottis (Miller). As the operator lifts superiorly and forward, the vocal cords should become directly visualized. The operator then passes the endotracheal tube with their right hand through the cords and inflates the cuff with air to create a seal. Tube placement should then be confirmed, and the patient sedated.

Figure 6. Macintosh (Mac) And Miller blades. Image Courtesy of Joshua Walker, MD, University of Central Florida.

Below is an excellent video describing how to perform Direct Laryngoscopy:

Video Laryngoscopy

Video laryngoscopy (VL) is similar to direct laryngoscopy as the blade and handle are used to expose the vocal cords and an ETT is passed into the trachea to secure the patient’s airway and provide ventilation. However, in VL the patient’s head can remain in the neutral position and the blade is passed directly over the tongue as opposed to the side. The operator performs VL by watching a screen instead of looking in the patient’s mouth. There are many advantages to video laryngoscopy including improved visualization in patients that have an anterior airway or large tongue. Additionally, VL allows the operator and any other physicians to have identical views of the patient’s airway, providing an early look for a second provider, as well as assistance in troubleshooting a challenging airway. The techniques for blade insertion and tube placement are modified slightly based on brand and viewpoint and should be practiced frequently to ensure success in a critical situation. Remember that VL blades generally require a hyperangulated stylet in the ETT for optimal success of placement.

|  |

Images used with permission from Verathon Corporation

Figure 7. Examples of Glidescope devices for video laryngoscopy.

Figure 8. Stylet for the Glidescope. Image Courtesy of Joshua Walker, MD, University of Central Florida.

There are video laryngoscopes that use a traditional Macintosh or Miller blade that can be used for either direct or video laryngoscopy. These devices have fiberoptics at the end of the blade which provide the video image. This allows an operator to initially perform DL, while giving any other physicians a similar view simultaneously. This is beneficial for allowing for instruction and advice if the airway becomes difficult.

There have been multiple studies assessing the first pass success with DL versus VL. There has been no proven difference between the two different methods. One key to remember is that if the airway is soiled with blood or vomitus this will make using VL much more difficult as the camera would become unusable.

Below is an excellent video on how to perform video laryngoscopy:

Bougie-Assisted Intubation

Another method to attempt is to place the endotracheal tube with an elastic bougie. Typically, if this can be passed, the performing clinician should feel the tracheal rings when placing the bougie for confirmation. Then, the endotracheal tube is fed over the bougie for placement. Sometimes, the physician will feed the endotracheal tube onto the bougie to facilitate delivery of the endotracheal tube (Figure 9.)

Figure 9. Preloaded Bougie onto endotracheal tube. Image courtesy of REBELEM and used under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. Original image located at: Bougie use in Emergency Airway Management (BEAM) - REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.

Below is an excellent video describing bougie-assisted intubation:

Considerations for Delayed Sequence Intubation

Utilization of a sedative medication, most likely ketamine, followed by a period of preoxygenation before medically induced paralysis. This can help in those patients who have delirium or another reason which precludes safe and optimal preoxygenation.

Awake intubation

Preferred method in those patients predicted to have a difficult intubation, those with severe metabolic derangements, or difficulty with mask ventilation. This requires a special skill set and involves several steps. These steps include topical application of anesthetics and pharmacologic facilitation. This is an advanced airway technique and only briefly covered in this chapter.

Topical lidocaine – 5% lidocaine paste placed on a tongue depressor and spread over the posterior third of the tongue, vallecular, and piriform recesses.

Atomized lidocaine – applied to the soft palate, posterior oropharynx, and epiglottis.

Ketamine – If topical anesthesia is accomplished may not be necessary but small aliquots may be beneficial

Confirmation of endotracheal tube placement

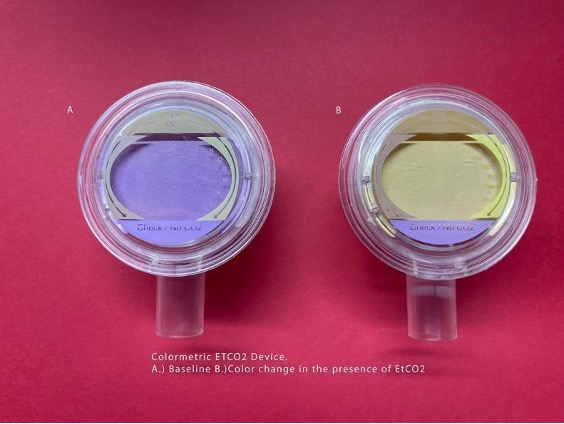

The first confirmation should be visualizing the endotracheal tube going through the vocal cords. The next step would be to utilize quantitative end-tidal CO2 monitoring to ensure that there is a proper waveform after intubation. Less ideal is the utilization of the colorimetric CO2 detector, which after 6 breaths should maintain a change from the standard purple color to persistent yellow when adequate ETCO2 is detected. This is less favorable to real-time quantitative EtCO2 but often the first choice in the ED. Chest radiograph should be obtained to ensure that the endotracheal tube is at a proper level 2-3 cm above the carina and below the level of the clavicles. Remember that chest radiograph cannot distinguish between esophageal and endotracheal intubation and that is why multiple methods of placement confirmation are used. Auscultation of bilateral breath sounds is also beneficial in ensuring that there is not a main-stem intubation, however is not considered confirmatory.

Figure 10. Capnography devices. Top- Colormetic capnography. Bottom- Continuous Capnography. Image Courtesy of Joshua Walker, MD, University of Central Florida.

The Failed Airway

Each airway attempt should be carefully planned as if it is going to be a failed airway. Multiple backups should be available and ready to use if needed. Preparation and mental conditioning are critical in order to stay calm and focused on the task. If you speak to the majority of seasoned emergency physicians, each will tell you of a humbling experience of a failed airway in their career and how they resolved the situation. When a difficult or failed airway is encountered, it is not unreasonable to call for help from another emergency physician, anesthesia provider, or surgical colleague. Pride should not get in the way of patient care.

A supraglottic airway such as a laryngeal mask airway (LMA) may help oxygenate and ventilate a patient with the failed airway until a definitive airway is established. An excellent video describing how to use a LMA is below:

If the emergency physician is unable to oxygenate or ventilate a patient with a failed airway, an emergent cricothyrotomy should be performed. A cricothyrotomy is a procedure (surgical or via Seldinger-technique) in which a breathing tube is inserted transcutaneously through the cricothyroid membrane in the neck into the trachea.

Figure 11. Percutaneous cricothyrotomy kit. Image courtesy of EMCurious.com and used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Original

image located at Surgical Airway Part 1: The Cricothyrotomy — EM Curious.

Ventilator management

Several tips should be considered for initial ventilator management in the newly intubated ED patient:

Ventilator management should aim for a goal of lung protective tidal volumes which are 6-8 mL/kg of ideal body weight.

Reduce the FiO2 to a goal of keeping the O2 saturation greater than 88-95% to prevent oxygen toxicity.

Addition of PEEP should be used to help reduce the FiO2 as well.

Respiratory rate should be titrated to the clinical reason that the patient was intubated.

Post-intubation sedation

Multiple different modalities can be used for sedation post-intubation. This is of key importance for the comfort of the patient as this is not very comfortable, especially if a long-acting paralytic was used. Also, there will be significant variation facility and practitioner preference at each facility, so learning the practices at the facility will be key.

Common medications include:

Propofol – short acting but no real analgesic effect. Likely to be combined with a narcotic medication such as fentanyl

Versed/Fentanyl combination – longer acting and can lead to increased length of stay in the icu.

Dexmedetomidine – takes longer to reach a steady state and may require one of the previously discussed medications prior to achieving goal sedation. Caution when using in patients with preexisting bradycardia.

Pearls and Pitfalls

Have all of the necessary equipment including multiple backups in case of a difficult airway.

Know the dosages and indications for the induction and paralytic medications. Pay special attention to post-intubation sedation and have that ready to go as well.

Have a very specific plan laid out in the event that the airway becomes increasingly more difficult to achieve than expected.

Consideration of underlying hemodynamics (i.e. blood pressure) should be a consideration prior to intubation. Intubation may have to wait until hemodynamics are stabilized with vasopressor agents to prevent peri-intubation cardiac arrest.

Always confirm the intubation with direct visualization and EtCO2. Chest x-ray cannot differentiate between esophageal or endotracheal intubation.

Case Study Resolution

Prehospital setup was completed including staff, respiratory therapy, bag valve mask, adjunctive airway equipment, mac 4 and miller 4 blades available, bougie available, and video laryngoscope were present in the room. The man was estimated to be 70 kg. BiPAP was attempted in the room but the patient would not tolerate it, therefore a decision was made for intubation. 20 mg of etomidate and 100 mg of rocuronium were given and the patient was subsequently intubated with a 8-0 endotracheal tube using a Mac 4 blade. Breath sounds were present bilaterally. Qualitative end-tidal CO2 was turned yellow after 6 breaths and the quantitative end-tidal CO2 was 35. Chest x-ray showed good placement of the endotracheal tube. Post-procedure sedation with propofol drip was initiated. Fentanyl bolus of 100 mcg was given with a fentanyl drip started as well. Ventilator was hooked up and the patient was admitted to the medical icu.

References

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network, Brower RG, Matthay MA, et al. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(18):1301-1308. doi:10.1056/NEJM200005043421801

Dodd KW, Prekker ME, Robinson AE, Buckley R, Reardon RF, Driver BE. Video screen viewing and first intubation attempt success with standard geometry video laryngoscope use. Am J Emerg Med. 2019 Jul;37(7):1336-1339. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2018.10.018. Epub 2018 Oct 16. PMID: 30528054.

Driver B, Dodd K, Klein LR, Buckley R, Robinson A, McGill JW, Reardon RF, Prekker ME. The Bougie and First-Pass Success in the Emergency Department. Ann Emerg Med. 2017 Oct;70(4):473-478.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.04.033. PMID: 28601269

Brian E. Driver, MD, Matthew E. Prekker, MD, Johanna C. Moore, MD, Alexandra L. Schick, Robert F.Reardon, and James R. Miner, MD Direct Versus Video Laryngoscopy Using the C-MAC for Tracheal Intubation in the Emergency Department, a Randomized Controlled Trial Academic Emergency Medicine 2016; 23: 433– 439 © 2016 by the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine

Driver, B.E., Prekker, M.E., Reardon R.F., Fantegrossi A., Brown III C.A. Comparing Emergency Department First-Attempt Intubation Success With Standard-Geometry and Hyperangulated Video Laryngoscopes. Annals of Emergency Medicine. Volume 76, Issue 3 September 2020

Girardis M, Busani S, Damiani E, et al. Effect of Conservative vs Conventional Oxygen Therapy on Mortality Among Patients in an Intensive Care Unit: The Oxygen-ICU Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;316(15):1583-1589. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.11993

Lebowitz PW, Shay H, Straker T, Rubin D, Bodner S. Shoulder and head elevation improves laryngoscopic view for tracheal intubation in nonobese as well as obese individuals. J Clin Anesth. 2012;24(2):104-108. doi:10.1016/j.jclinane.2011.06.015

Levitan RM, Everett WW, Ochroch EA. Limitations of difficult airway prediction in patients intubated in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44(4):307-313. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.05.006

Mosier Jarrod M., Greenberg Jeremy A.. Airway Management. In: Mattu A and Swadron S, ed. CorePendium. Burbank, CA: CorePendium, LLC. https://www.emrap.org/corependium/chapter/rec0HG8tlkuLhqzGb/Airway-Management#h.4qcj7rgeclyj. Updated June 24, 2022. Accessed September 19, 2022.

Stauffer JL: Medical management of the airway. Clin Chest Med 1991;12(3):449–482.

Stone DJ, Gal JT: Airway management, in Miller RD (ed): Anesthesia, vol 2. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1990:1265–1292

Tsan SEH, Lim SM, Abidin MFZ, Ganesh S, Wang CY. Comparison of Macintosh Laryngoscopy in Bed-up-Head-Elevated Position With GlideScope Laryngoscopy: A Randomized, Controlled, Noninferiority Trial. Anesth Analg. 2020;131(1):210-219. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000004349

Weingart SD, Levitan RM. Preoxygenation and Prevention of Desaturation During Emergency Airway Management. Ann Emerg Med. 2012 Mar; 59(3): 165-75.e1. Epub 2011 Nov 3. Review