Pediatric Pharyngitis

Objectives

Upon finishing this module, the student will be able to:

- List common etiologies of pediatric pharyngitis.

- Discuss the evaluation of the "sore throat."

- Discuss the management of Group A streptococcal pharyngitis.

Contributors

Update Author: Caitlin Valentino, MD, MEd, MS.

Original Author: Robert W. Wolford, MD, MMM.

Update Editor: Navdeep Sekhon, MD.

Last Updated: August 2024

Introduction

Acute pharyngitis, or "sore throat," is a frequent complaint seen in the pediatric emergency department (ED). Pharyngitis typically results from respiratory droplet transmission, but can also be transmitted through contact with infected surfaces/fomites. The most common causes of acute pharyngitis are viruses. Group A streptococci (GAS) is the most common bacterial etiology of pediatric pharyngitis and needs to be treated with antibiotics. Although pharyngitis is typically self-limited and uncomplicated, the clinician must be alert for the rare and potentially life-threatening diseases that may initially masquerade as a "sore throat."

Selected Etiologies of Sore Throat

| Organism/Disease | Clinical Manifestation (in addition to sore throat) | |

| Life-Threatening | Epiglottitis | Fever, stridor, drooling |

| Peritonsillar Abscess | Unilateral soft palate swelling, trismus | |

| Retropharyngeal Abscess | Neck pain and decreased range of motion, fever, dysphagia | |

| Diphtheria/Corynebacterium diphtheriae | Grey adherent membrane covering tonsils/oropharynx, swollen neck | |

| Tracheitis | Anterior neck tenderness, hoarseness | |

| Lemierre Syndrome (complication of pharyngitis) | Fever, neck tenderness and swelling, sepsis | |

| Bacterial | Group A streptococci | Pharyngitis, scarlet fever |

| Neisseria Gonorrhoeae | Dysphagia, lymphadenopathy, tonsillar exudates | |

| Mycoplasma, Chlamydia Pneumonia | Respiratory illness, unclear importance in pharyngitis | |

| Viral | Rhinovirus, Coronaviruses | Upper respiratory illness (URI) |

| Adenovirus | URI, conjunctivitis | |

| Influenza | URI, fever | |

| HIV | Fever, lymphadenopathy, weight loss | |

| Coxsackie Virus | Hand-foot-mouth disease | |

| Epstein Barr Virus/Mononucleosis | Fever, fatigue, lymphadenopathy | |

| Other | Chemical Irritation | Gastro-esophageal reflux, cigarette smoke, mouth breathing |

| Environmental Allergies | Itchy eyes, rhinorrhea | |

| Foreign Body | Unilateral pain, history of choking episode |

The initial evaluation of any patient with a chief complaint of sore throat, as with any ED patient, should begin with a rapid cardiopulmonary assessment to determine “sick vs not sick.”

Before entering the room, quickly review the chief complaint, triage note, and vital signs. Fever and tachycardia are common findings in pediatric patients with acute pharyngitis. Significant vital sign derangements such as hypoxia or hypotension are red flags suggesting a more severe etiology. Upon entering the room, observe how the child is positioned. A patient sitting comfortably in a parent’s lap is unlikely to be suffering from a serious or life-threatening cause of their sore throat. Alternatively, if you observe a child who is drooling, leaning forward in a tripod position, in severe distress, lethargic or altered, then symptoms are suggestive of a serious or life-threatening illness. The patient should be prepared for resuscitation and possible airway management.

Primary Survey

- Airway: Is the airway intact? Age-appropriate phonation is reassuring. Stridor, drooling, or "hot potato voice" should prompt further evaluation.

- Breathing: Breathing is normal in most cases of acute pharyngitis. Fever may cause tachypnea. Signs of lower respiratory tract infection suggest other etiologies.

- Circulation: Tachycardia is common in children, especially when associated with fever or pain. Hypotension or other signs of poor perfusion (weak pulses, delayed capillary refill, mottling of skin) are not expected and suggest an emergent need for resuscitation and evaluation for serious or life-threatening etiology.

After the initial primary survey is completed, an appropriate history and physical examination should be obtained. Potential diagnoses should guide further information-gathering from the family. Key components of the history of acute pharyngitis include time course of illness, fever curve, associated symptoms, presence of sick contacts, and immunization status.

Group A Streptococcus (GAS) Pharyngitis

GAS pharyngitis typically presents with an acute onset of sore throat. School-age children and adolescents are most commonly affected, with incidence peaking at seven-eight years old. Associated signs and symptoms include fever, sore throat, headache, tonsillar exudate, and tender anterior cervical lymphadenopathy. Younger children are more likely to present with fever and irritability. Some children will present with scarlet fever, which is associated with a diffuse sandpaper-like rash.

Epiglottitis

Pediatric epiglottitis is a rare but serious condition that causes inflammation of the epiglottis. Thankfully, the incidence of this life-threatening condition has decreased due to the usage of the Haemophilus influenzae type B vaccine. The inflammation can block the airway, creating a true airway emergency. Epiglottitis classically presents as acute respiratory distress, and concerning physical examination signs include:

- Patient may be in a tripod or "sniffing position" to help open their airway.

- Classically, the examination of the posterior oropharynx may be benign. However, aggressive examination of the posterior oropharynx is discouraged as it may worsen the airway.

Peritonsillar Abscess

Peritonsillar abscesses are the most common deep neck infections and are often polymicrobial. Classically, the patient will present with sore throat, fever, odynophagia, and voice changes. Trismus can also be present. The physical examination will demonstrate:

- Unilateral swelling of the posterior oropharynx.

- Elevation of the soft palate.

- Uvular deviation pointed away from the affected tonsil.

If severe, the patient may also have respiratory distress.

Testing should be conducted based on the patient’s presenting symptoms. Most patients presenting with a sore throat and other viral symptoms such as cough and rhinorrhea do not require any testing. In patients who play contact sports or are at risk of splenic injury, consider testing for EBV infection. Blood work is not usually indicated unless there are significant concerns for dehydration due to decreased oral intake.

GAS Pharyngitis

Children over three years of age presenting with signs and symptoms consistent with GAS pharyngitis (pharyngeal exudate, enlarged tonsils, odynophagia, fever, tender/enlarged anterior cervical lymph nodes) should be tested (children less than the age of three rarely have GAS pharyngitis). Consider testing in patients two-three years of age with close family contact known to have a GAS infection. A test specimen should be obtained by swabbing the posterior pharynx and both tonsils. A parent or a second staff member may need to assist in holding the patient while the specimen is obtained. Test results are reliant on the quality of the sample obtained. Several rapid GAS pharyngitis tests are available. Specificity of these tests is generally high (few false positives) but sensitivity varies (false negatives can occur). Negative rapid antigen tests should be confirmed with a second specimen sent for a culture. Some centers may use a rapid polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or isothermal nucleic acid amplification (NAAT) tests. These tests have high sensitivity (few false negatives) and generally do not require culture confirmation.

The Centor Score can be used to help guide the need for testing. The score consists of four criteria: tonsillar exudates, tender anterior cervical lymphadenopathy, fever, and an absence of cough. Generally, patients with three or more criteria should be tested for GAS. Use of the score does not replace testing, and patients should not be treated with antibiotics based on the score alone.

Epiglottitis

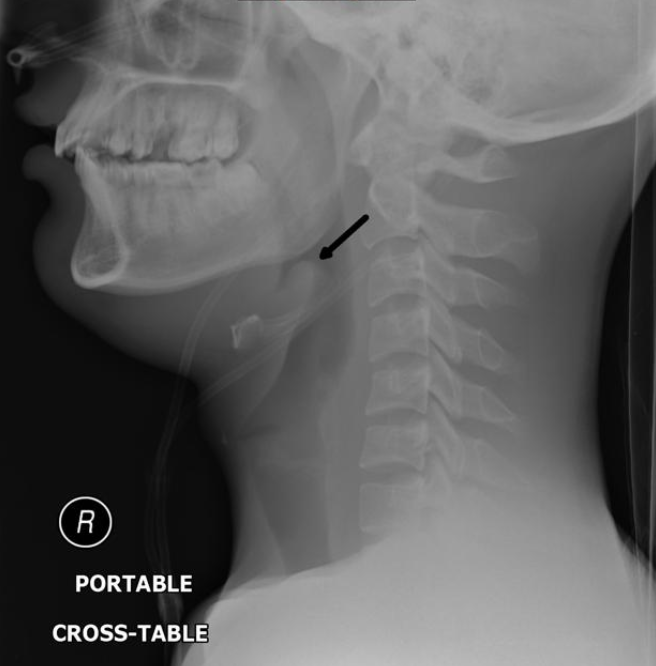

Epiglottitis is classically a clinical diagnosis, and emergent consultation of ENT and anesthesia should not be delayed pending imaging as the airway can rapidly decompensate. If the patient can tolerate it, a lateral neck X-ray can show a "thumbprint" sign, which shows an enlarged epiglottis. If the patient is stable, a CT of the neck should also be performed.

Figure: Thumbprint sign in epiglottitis. Image courtesy of Andrew Ho. Used under the Creative Commons Non-Commercial Attribution, Sharealike license.

Peritonsillar Abscess

The diagnosis of a peritonsillar abscess is classically made clinically based on examination of the posterior oropharynx. Additional imaging modalities that can be used include ultrasonography and CT scan imaging.

Symptomatic treatment with analgesia and hydration should be initiated in the ED for the majority of patients with acute pharyngitis. Typically, oral acetaminophen and/or ibuprofen and oral rehydration is adequate. Intravenous fluids may be required, particularly in those patients who are unable to tolerate the oral route due to pain.

GAS Pharyngitis

The use of antibiotics for GAS pharyngitis is thought to reduce the risk of rheumatic fever and suppurative complications (ex. mastoiditis, acute otitis media and sinusitis, peritonsillar abscess, cervical lymphadenitis), decrease the risk of spread to close contacts, and decrease the severity of the patient’s symptoms. The use of antibiotics must be balanced against the societal risk of the development of antibiotic resistance and the patient risks of antibiotic associated adverse events (ex. allergic reaction, diarrhea, C. difficile colitis).

Only children with a positive test (rapid test or culture) for GAS should receive antibiotic therapy. Below are some suggested antibiotics and doses:

| Drug and Route | Dose | Duration | |

| First-Line Therapies | Penicillin V, oral | <27kg: 250mg two-three times per day >27kg: 500mg two-three times per day | Ten days |

| Penicillin G Benzathine, intramuscular | <27kg: 600,000 units >27kg: 1.2 million units | Once | |

| Amoxicillin, oral | 50mg/kg once or twice daily, max 1000mg/day | Ten days | |

| Penicillin-Allergic Patients (Non-Anaphylactic Reaction) | Cephalexin, oral | 20mg/kg/dose twice daily (max 500mg/dose) | Ten days |

| Penicillin-Allergic Patients (Anaphylactic Reaction) | Clindamycin, oral | 20mg/kg/day divided into three doses (max 900 mg/day) | Ten days |

Although they can be used in penicillin-allergic patients, clindamycin and the macrolides have high resistance rates and can lead to treatment failure.

On discharge, parents should be advised to provide acetaminophen and/or ibuprofen for pain and fever control and to encourage adequate fluid intake. Patients should be re-evaluated in 48 to 72 hours if they are not symptomatically improving and immediately if they worsen in any way (ie. increasing pain, inability to swallow, inability to take adequate oral fluids and medications, drooling, or difficulty breathing). The use of systemic steroids lacks sufficient evidence currently to recommend its routine use. Children may return to school after they have been on antibiotics for at least 24 hours and if they are afebrile and symptomatically improved.

Epiglottitis

The patient should be provided supplemental oxygen in the least invasive way possible. Emergent consultation with anesthesiology and ENT is required as the patient may need an emergent surgical airway. It is critical to ensure the comfort of the patient as to not exacerbate any airway deterioration. If the airway is rapidly decompensating, the physician can try bag-valve mask ventilation, fiberoptic intubation, needle cricothyrotomy, and tracheostomy (if trained). Antibiotics should also be administered.

Peritonsillar Abscess

Any airway emergency should be managed with the use of supplemental oxygenation, intubation, and/or cricothyrotomy as needed. Fortunately, for peritonsillar abscess, this is rare. The treatment of peritonsillar abscess includes the use of antibiotics, including amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, penicillin and metronidazole, or clindamycin. It is also important to note that there is some evidence that steroids can provide some symptomatic relief with regards to pain and swelling. Mild cases may improve with antibiotics alone. More severe cases may benefit from needle aspiration in the ED.

- Always consider serious and potentially life-threatening etiologies of sore throat.

- For epiglottitis, emergent consultation with ENT and anesthesiology can be life-saving. In addition, helping the patient remain calm can be life-saving and prevent further airway swelling.

- Use narrow spectrum antibiotics.

- Remind parents to change out the patient's toothbrush 24-48 hours after antibiotic initiation to prevent reinfection for GAS pharyngitis.

- Systemic steroids are not recommended for symptomatic relief of acute pharyngitis.

- Untreated GAS pharyngitis can trigger post-infectious syndromes of poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis and acute rheumatic fever.

- Cairns C, Kang K. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2021 Emergency Department Summary Tables. Accessed 2024 Aug.

- Lamichhane A, Radhakrishnan S. Diphtheria. StatPearls. 2024 Jan.

- Bhavsar SM. Group A Streptococcus Infections. Pediatr Rev. 2024.

- Kimberlin DW, et al. Red Book: 2021-2024 Report on the Committee on Infectious Diseases. American Academy of Pediatrics.

- Fine AM, Nizet V, Mandl KD. Large-Scale Validation of the Centor and McIsaac Scores to Predict Group A Streptococcal Pharyngitis. Arch Intern Med. 2012 Jun.

- Wessels MR. Streptococcal Pharyngitis. N Engl J Med. 2011.

- Choby BA. Diagnosis and Treatment of Streptococcal Pharyngitis. Am Fam Physician. 2009.

- Wolford RW. Evaluation of the Sore Throat. Diagnostic Testing in Emergency Medicine. WB Saunders Company. 1996.

- Shulman ST, Bisno AL, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Group A Streptococcal Pharyngitis. Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2012.

- Ebell MH, Smith MA, et al. The Rational Clinical Examination: Does this Patient Have Strep Throat?. JAMA. 2000.

- McIsaac WJ, White D, et al. A Clinical Score to Reduce Unnecessary Antibiotic Use in Patients with Sore Throat. Can Med Assoc J. 1998.

- Hersh AL, Jackson MA, Hicks LA. Principles of Judicious Antibiotic Prescribing for Upper Respiratory Tract Infections in Pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2013.

- Snellman L, Adams W, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Respiratory Illness in Children and Adults. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. 2013.