Mesenteric Ischemia

Written by: Sundip Patel, MD, Cooper Medical School of Rowan University,

Editor: David Cheng, MD, Case Western Reserve University,

Update: November 2019

Case Study

A 78-year-old female with a history of atrial fibrillation presents with sudden onset of abdominal pain for the past 4 hours. The pain is severe and diffuse. She has had some nausea, but no diarrhea, dysuria, hematuria, or rectal bleeding. She had a normal bowel movement approximately 8 hours ago. On physical examination, you note the patient to be grimacing in pain while holding her abdomen. Conjunctiva are pink and there is no scleral icterus. Her heart exam reveals an irregularly irregular rhythm. Her abdominal exam reveals a soft, non-distended abdomen with no rebound but mild diffuse abdominal tenderness. Your abdominal exam is not consistent with the level of pain the patient is reporting or the obvious discomfort that is visible to you.

Objectives

By the end of this module, the student will be able to:

- Recognize the importance of early consideration for mesenteric ischemia in the differential diagnosis of abdominal pain.

- Describe the classic presentation for mesenteric ischemia.

- Identify the four different causes of mesenteric ischemia and their clinical presentations.

- Discuss the utility of laboratory and radiographic testing in diagnosing mesenteric ischemia.

- Discuss treatment options for mesenteric ischemia.

Introduction

In spite of all our technological advances in medicine, mesenteric ischemia remains a very difficult disease process to identify early. Often patients will present with vague and variable signs and symptoms such as poorly localized abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. These non-specific signs and symptoms can be associated with an extremely wide variety of abdominal pathologies including, but not limited to, abdominal aortic aneurysm, volvulus, perforated viscus, incarcerated hernia, appendicitis, biliary colic, and renal colic. It is these vague findings and broad differential for mesenteric ischemia that lead physicians down an incorrect diagnostic pathway.

Also, the delay in diagnosis of mesenteric ischemia can be disastrous. If mesenteric ischemia is not considered early in the patient’s Emergency Department (ED) presentation, then the intestines will rapidly become gangrenous and infarct leading to multisystem organ failure, sepsis, and eventual death. Studies have found mortality rates of 80% - 100% if there is a treatment delay of over 24 hours from symptom onset! The difficulty in early diagnosis and delayed treatment is why the morbidity and mortality rates for mesenteric ischemia still remain high today.

Fortunately, mesenteric ischemia is not a common disease as it accounts for 1% of admissions to the hospital for acute abdominal processes. However, the incidence may be rising because of an aging population with significant co-morbidities such as atrial fibrillation, atherosclerosis, congestive heart failure, and hypercoagulability. The main goal is to identify mesenteric ischemia early in undifferentiated abdominal pain patients so that rapid revascularization to the mesentery can be achieved preventing bowel infarction and its subsequent complications.

Initial Actions and Primary Survey

Mesenteric ischemia is a time-sensitive disease process as delays in diagnosis will lead to increased morbidity and mortality, especially in elderly patients. The first and most important initial action is to consider mesenteric ischemia in the differential diagnosis of all elderly patients with abdominal pain. The importance of early consideration and diagnosis of mesenteric ischemia cannot be overemphasized. Other initial actions will include large bore intravenous access, fluid resuscitation, and telemetry monitoring. Obtain an ECG to see if the patient has atrial fibrillation which can put them at risk for an embolic cause of mesenteric ischemia. Discuss the case with the surgeons as early as possible so that they can monitor for changes in the patient’s abdominal exam. An initial benign, soft abdominal exam can become peritoneal and that may lead the surgeons to take the patient to the operating room rapidly in order to preserve as much bowel as possible. Consider aggressive fluid administration early in the patients ED course as well as addressing any other abnormalities in the primary survey. If the patient is becoming hypoxic or has dyspnea due to fluid resuscitation, apply oxygen via nasal cannula, a non-rebreather mask, or non-invasive positive pressure ventilation via BiPAP. Consider intubation if their breathing worsens despite those measures. If the patient is hypotensive, make sure fluid resuscitation is adequate as vasopressors will worsen mesenteric blood flow and thereby worsen the amount of ischemia. Consider broad spectrum antibiotics and anticoagulation. The Diagnostic Testing section will describe what laboratory and radiographic tests will need to be done.

Presentation

The “classic” presentation for mesenteric ischemia will be in a patient over the age of 60. Women are three times more likely than men to have acute mesenteric ischemia. Patients will present with sudden abrupt onset of abdominal pain which may be associated with nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. The abdominal pain will initially be severe and diffuse without any localization. One of the distinctive findings in mesenteric ischemia is that the abdominal pain is out of proportion to their physical exam. The patient may be screaming in pain, but their initial abdominal exam can be soft with no guarding or rebound. This is because the ischemia is in the wall of the hollow viscus of the intestine and therefore does not cause the same peritoneal signs that would be present in appendicitis, cholecystitis, and other more localized processes. As the disease progresses and the bowel infarcts, the patient will develop abdominal distension with guarding, rebound, and absence of bowel sounds. They may develop abdominal wall rigidity. Bloody diarrhea and heme-positive stools are a late finding after bowel has infarcted.

The aforementioned description is the classic presentation, often seen on standardized tests. Unfortunately, in practice patients may present with postprandial pain or generalized abdominal pain that can mimic other disease processes making the diagnosis of mesenteric ischemia less obvious. The postprandial pain is similar to exercising with unstable angina in the myocardium: with decreased blood supply to the intestines, when patients eat and demand higher oxygen utilization during digestion, the flow is insufficient and causes ischemic pain. This is why this type of pain is often referred to as abdominal angina. To truly understand the real-life presentations of mesenteric ischemia, the four different etiologies of this disease must be analyzed: mesenteric artery embolism, mesenteric artery thrombosis, mesenteric vein thrombosis, and non-occlusive ischemia.

Mesenteric Artery Embolus

This is the most common cause of mesenteric ischemia accounting for 40-50% of cases. Onset of symptoms is sudden due to the acute nature of an embolus lodging in the artery with little time for collateral circulation to form. Patients with mesenteric artery embolism will present with the classic abdominal pain out of proportion to exam. Risk factors for mesenteric artery embolism include arrhythmias (atrial fibrillation being the most common), post-myocardial infarction with mural thrombi, valvular heart disease, and recent angiography causing a showering of plaque emboli downstream.

The most common location of an embolus is in the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) due to the oblique 45-degree angle of the SMA from the aorta. The embolism usually lodges distal to the origin of the middle colic artery, sparing the duodenum and proximal jejunum as compared to a mesenteric artery thrombosis which causes a more proximal blockage leading to more extensive bowel ischemia.

Mesenteric Artery Thrombosis

This generally occurs due to long standing atherosclerosis at the origin of the SMA. Over time, the lumen of the SMA becomes more stenotic due to plaque buildup. This decreased flow to the intestines can give the patient vague and insidious symptoms such as abdominal angina, diarrhea, fear of food, and weight loss. The constellation of these symptoms is termed chronic mesenteric ischemia and up to 80% of patients with mesenteric artery thrombosis will have these symptoms. If the plaque ruptures acutely, the patient can present with sudden onset of abdominal pain similar to what is seen in mesenteric artery embolus patients.

Mesenteric Vein Thrombosis (MVT)

MVT occurs in younger patient populations and is most likely due to hypercoagulable states (Factor V Leiden, Protein C deficiency, etc.). The superior mesenteric vein is most commonly involved in MVT and the abdominal pain onset and location can be variable. Most patients with MVT do not have postprandial abdominal pain or food fear as seen in mesenteric artery thrombosis. They usually present with an insidious onset of pain that is not as severe as pain caused by a mesenteric artery embolism. This may explain why patients wait 5-14 days from onset of pain to seek medical help. Other MVT risk factors besides hypercoagulable states include recent surgery, malignancy, cirrhosis. In addition, 50% of patients with MVT have a family history of venous thromboembolism.

Non-occlusive Ischemia

Non-occlusive ischemia occurs in low flow states in the absence of an arterial or venous occlusion. Any condition associated with decreased cardiac output can cause non-occlusive ischemia including cardiogenic shock, septic shock, congestive heart failure, hypovolemia, arrhythmias, and prolonged vasoconstrictor use. This disease process often develops during hospitalization in sick patients suffering from other illnesses so a high index of suspicion is required to diagnose it. Treatment involves targeting the underlying cause and correcting it. There is a high mortality rate in these patients as they are generally very ill prior to the development of the non-occlusive ischemia.

Diagnostic Testing

Labs

Generally, labs are not helpful in making the diagnosis of mesenteric ischemia from other abdominal pathologies as no single lab has the sensitivity and specificity to rule in or rule out the disease. The white blood cell count is commonly elevated, but is a nonspecific finding and a normal white count does not rule out the disease. Hemoconcentration, elevated amylase levels, and metabolic acidosis may also be found in mesenteric ischemia, but are non-specific findings. An elevated lactate level is sensitive for mesenteric ischemia however is frequently seen in late disease after bowel infarction. Lactate cannot be used as a negative screening test. It can be followed during the disease to determine is bowel loss is occuring. One study did show some promise with D-dimer testing. In that study, no patient presenting with a normal D-dimer had intestinal ischemia. Further studies focusing on D-dimer use in mesenteric ischemia are required.

Plain Radiography

Plain films of the abdomen will typically be normal early in the course of the disease. An upright abdominal x-ray can be used to rule out free air from a perforated viscus. As the ischemia progresses, subtle signs such as thickening of bowel wall and distended loops of bowel can be seen, but like the labs are non-specific signs. Pneumatosis of the intestinal wall can afterwards be seen on plain film, but is a late finding when bowel has become necrotic.

Angiography

Mesenteric angiography was the gold standard for mesenteric ischemia but has been replaced in recent years by multidetector CT angiography of the abdomen and pelvis due to advances in CT imaging. Mesenteric angiography can identify the site and type of occlusion including non-occlusive ischemia. Medications such as papaverine (a vasodilator) and thrombolytics can also be infused during mesenteric angiography allowing for interventions on emboli and thrombi. The downsides of angiography are that it is an invasive and lengthy procedure and may not be readily available at all hospitals or all times of day. In addition, angiography will not evaluate other causes for abdominal pain such as bowel obstruction, renal colic, genitourinary disorders and gynecologic diseases.

Multidetector CT Angiography (CTA) of Abdomen/Pelvis

CTA of the abdomen/pelvis has largely replaced mesenteric angiography as the tool to diagnose mesenteric ischemia. Recent studies have shown CTA to have a sensitivity of 93% and specificity up to 100% for mesenteric ischemia. In comparison to angiography, CTA is fast, less invasive, and more readily available. In addition to the vascular findings of thrombus and emboli, CTA can also demonstrate subtler signs of mesenteric ischemia such as circumferential thinking of the bowel wall, bowel dilatation, bowel wall attenuation, and mesenteric edema which may not be seen on angiography. Other pathologies such as colitis, appendicitis and bowel obstruction, which may mimic mesenteric ischemia, can also be diagnosed on CTA. It is for these reasons that CTA is the initial test to obtain for patients in who the diagnosis of mesenteric ischemia is being considered.

Unlike angiography, CTA cannot provide therapy, but, can help triage patients towards those who can undergo angiography and those who should go to the operating room immediately. CT angiography requires intravenous contrast to be administered, and contraindications to iodinated contrast should be considered prior to obtaining the examination. Renal insufficiency is often comorbid with patients who have multisystem disease and the theoretical risk of contrast induced nephropathy should be weighed against the risk of missing the diagnosis if angiography is not performed. Oral contrast is not indicated.

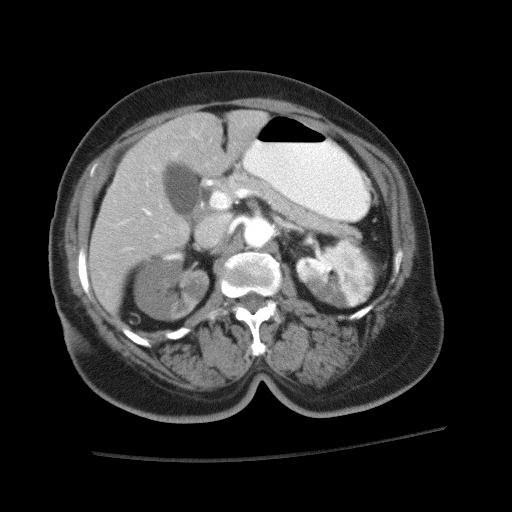

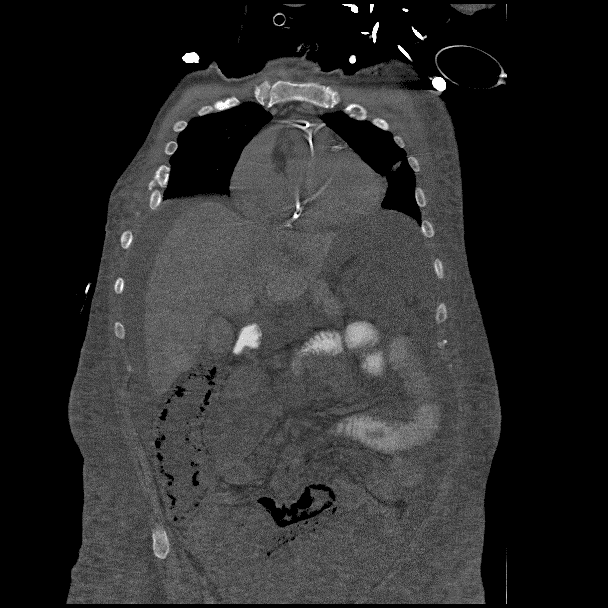

Below are some images of CTA diagnosing mesenteric ischemia.

Sagittal Image of SMA thrombus (white arrow pointing at thrombus)- Image created by Dr. Sundip Patel. Used by permission. CC 4.0 BY-NC-SA, 2019

Axial Image of SMA thrombus (red arrow pointing at thrombus)Image created by Dr. Sundip Patel. Used by permission. CC 4.0 BY-NC-SA, 2019

Pneumatosis of bowel wall which can be a sign of mesenteric ischemia. Red arrow pointing at an area of pneumatosis. Image created by Dr. Sundip Patel. Used by permission. CC 4.0 BY-NC-SA, 2019

Ultrasonography

There are difficulties with using ultrasound to diagnose mesenteric ischemia. A skilled ultrasonographer along with a radiologist who is trained in interpreting the images is required. Obese patients, copious bowel gas, and prior abdominal surgeries will limit the quality of the ultrasound images. Distal emboli are also difficult to see on ultrasound. Due to these reasons, ultrasound is not a first line study for diagnosis of mesenteric ischemia.

Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA)

MRA can help identify proximal occlusions, but it is limited as a diagnostic test by not being available at all hospitals and all times of day as well as being a lengthy test which could delay surgical intervention.

Treatment

Initial treatment in mesenteric ischemia must focus on stabilization and resuscitation. Two large bore IVs with crystalloid fluids are necessary in patients, especially those who are hypotensive. Continuous monitoring of vital signs is paramount. Broad spectrum antibiotics covering bowel flora, such as ceftriaxone and metronidazole, should be started. Early surgical consultation is highly recommended so that the surgeons can closely follow the patient, do serial abdominal examinations, review the CT imaging with radiology, and take the patient to the OR rapidly thus saving as much bowel as possible. Anticoagulation should be considered and discussed with the surgeons. A shorter-acting anticoagulant such as an unfractionated heparin infusion may be optimal as it can be shut off quickly if the patient is to go to the OR.

The ultimate management of acute mesenteric ischemia is challenging, ever-changing and diverse. Treatment can range from non-operative management with medications, intravascular thrombolytics, percutaneous angioplasty, operative revascularization, resection of bowel, or a combination of therapies. The treatment for each patient must be individualized depending on the patient's state of health, cause of ischemia, and resources that are available. Listed below are the treatments based on the four etiologies of mesenteric ischemia.

Mesenteric Artery Embolism

The treatment of choice for mesenteric artery embolus is embolectomy and bowel visualization to assess for signs of necrosis. Percutaneous treatment with thrombolytics directly infused into the artery containing the embolism during angiography is another option for patients who do not have peritoneal signs or are non-operative candidates. The drawback is that bowel viability generally assessed during laparotomy cannot be done. In addition, contraindications to thrombolytics including recent surgery or GI bleed, recent stroke, and peritoneal signs indicating bowel infarction must be considered.

If operative management is decided, revascularization is done first so that ischemic-looking bowel can recover with the return of blood flow. Once blood flow is reestablished, any bowel that remains infarcted and necrotic is then resected. A “second look” procedure 24-48 hours later may be done if the viability of a section of bowel was in question during the first surgery.

Mesenteric Artery Thrombosis

In this etiology, heparin should be started as soon as the diagnosis is made and prior to surgery. The corrective operative measures for mesenteric artery thrombus are the same as for mesenteric artery embolism. For non-operative candidates, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty with stenting is an option. In patients with chronic mesenteric ischemia and mesenteric artery thrombosis, there has been complete resolution of symptoms after intervention.

Mesenteric Vein Thrombosis

If there are signs of infarction, then operative care is required. Otherwise thrombectomy with endarterectomy or distal bypass is the first choice of treatment. Anticoagulation is routinely administered to prevent thrombus reoccurrence. These patients will generally require life-long anti-coagulation.

Non-occlusive Mesenteric Ischemia

The treatment is to diagnose the underlying cause of the low flow state to the bowel such as sepsis or decreased cardiac output. Patients who develop peritoneal signs must go to the OR.

Pearls and Pitfalls

- Mesenteric ischemia is a time-sensitive diagnosis that, if missed, can lead to bowel necrosis, organ failure, and death.

- The signs and symptoms of mesenteric ischemia are vague with "pain out of proportion to exam" being the classic presentation.

- The mortality rate for mesenteric ischemia remains high despite new diagnostic testing.

- The four causes of mesenteric ischemia are mesenteric artery embolism (commonly due to atrial fibrillation), mesenteric artery thrombosis (commonly due to atherosclerosis), mesenteric vein thrombosis (commonly due to hypercoagulability) and non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia (commonly due to low flow states).

- Laboratory testing is not sensitive or specific for diagnosing mesenteric ischemia.

- CT angiography has replaced mesenteric angiography as the initial imaging study due to being less invasive, readily available, and having the ability to diagnose other causes for abdominal pain.

Case Study

Your 78-year-old female had CT angiography done which demonstrated an embolus in her superior mesenteric artery and bowel wall thickening. The patient has received IV fluids, antibiotics, and heparin, but still has pain. The surgeons decide to take her to the operating room to assess for bowel ischemia and necrosis. On exploratory laparotomy, they note a segment of small intestine that appears ischemic, but no necrosis. The clot from the superior mesenteric artery is removed and the bowel is re-evaluated. The segment of bowel that was ischemic in appearance is now pink. Your patient has an uncomplicated post-op recovery and is thankful that your early diagnosis of mesenteric ischemia saved her from having any bowel resected.

References

Bala M, Kashuk J, Moore EE, et al. Acute Mesenteric Ischemia: Guidelines of the World Society of Emergency Surgery. World J Emerg Surg. 2017; 12: 38. PMID: 28794797https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28794797

Ehlert, BA. Acute Gut Ischemia. Surg Clin North Am. 2018 Oct; 98(5): 995-1004. PMID: 30243457 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30243457

Kanasaki S, Furukawa A, Fumoto K, et al. Acute Mesenteric Ischemia: Multidetector CT Findings and Endovascular Management. Radiographics. 2018; 38(3): 945-961. PMID: 29757725 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29757725

Liao G, Chen S, Cao H, et al. Review: Acute Superior Mesenteric Artery Embolism: A Vascular Emergency Cannot be Ignored by Physicians. Medicine. 2019; 98(6):e14446. PMID: 30732209 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30732209

Singh M, Long B, Koyfman A. Mesenteric Ischemia: A Deadly Miss. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2017; 35 (4): 879-888. PMID: 28987434 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28987434