Trauma

Author Credentials

Last Update: November, 2019

Case Study

“We have a motor vehicle accident 5 minutes out per EMS report.”

47-year-old male unrestrained driver ejected 15 feet from car arrives via EMS. Vital Signs: BP: 100/40, RR: 28, HR: 110. He was initially combative at the scene but now difficult to arouse. He does not open his eyes, withdrawals only to pain, and makes gurgling sounds. EMS placed a c-collar and backboard, but could not start an IV.

What do you do?

Objectives

Upon completion of this self-study module, you should be able to:

- Describe a focused rapid assessment of the trauma patient using an organized primary and secondary survey.

- Discuss the components of the primary survey.

- Discuss possible pathology that can occur in each domain of the primary survey and recommend treatment/stabilization measures.

- Describe how to stabilize a trauma patient and prioritize resuscitative measures.

- Discuss the secondary survey with particular attention to head/central nervous system (CNS), cervical spine, chest, abdominal, and musculoskeletal trauma.

- Discuss appropriate labs and diagnostic testing in caring for a trauma patient.

- Describe appropriate disposition of a trauma patient.

Introduction

Nearly 10% of all deaths in the world are caused by injury. Trauma is the number one cause of death in persons 1-50 years of age and results in significant life years lost. According to the National Trauma Data Bank, falls are the leading cause of traumatic injury followed by motor vehicle collisions (MVCs). Firearm related injuries had an overall mortality rate of 4.39% in 2016. Trauma patients can consume a significant amount of time and resources due to their acuity and complexity. Having an organized approach to the trauma patient will help reduce errors and avoid missing potentially life threatening injuries. In addition to understanding injury patterns, having a high suspicion for certain rare but significant pathology will improve the care you provide to this vulnerable population.

Initial Actions and Primary Survey

The trauma patient presents unique challenges to the Emergency Physician. Because these patients are often young and otherwise healthy, they are able to compensate for many of the injuries they sustain and may not manifest signs of shock until they are on the verge of circulatory collapse. These patients may present via EMS from the scene or through triage hours or days after sustaining the injury. Being prepared and organized in your assessment of these patients is critical to not missing injuries. In addition, the patient who is initially stable may decompensate at any point in their care. Trauma patients need frequent reassessments to truly understand the entirety of their condition. In preparation for this patient’s arrival, consider life threats and possible interventions that may need to be performed. Ensure the team has appropriate personal protective equipment donned, verify the airway equipment, suction, monitors, vascular access materials and other equipment depending on the level of care that can be provided.

The evaluation of trauma patients should have a standardized approach to ensure that no potential injuries are overlooked. This standard evaluation falls in to a primary survey and a secondary survey. An easy way to remember this is the ABCDE method.

- A: Airway (Maintenance with CERVICAL SPINE protection)

- B: Breathing and Ventilation

- C: Circulation with hemorrhage control / shock assessment

- D: Disability: Neurological status

- E: Exposure/Environmental control

Correction of any abnormality within the ABCs should be made before moving to the next. Trauma patients have the potential to have significantly compromised ABCs depending on the mechanism of injury. This section will help to understand the trauma related specifics the primary survey. This chapter will focus on the overall approach to the trauma patient and much of the specific etiologies will be addressed in subsequent chapters (see Chest Trauma, Abdominal Trauma, Neck Trauma, Closed Head Injury)

Presentation

Given that the presentation of traumatic injury can vary greatly depending the mechanism it is impossible to summarize the presentation of all possible traumatic injury. At this level of training it is important to develop the foundational evaluation skills that can be applied broadly to all trauma patients

A - Airway

Initial assessment should evaluate not only the patient’s current airway but the potential for the airway status to change. Is the airway patent and is it likely to stay that way?

To do this, have the patient speak to establish patency and to evaluate for voice change and stridor. Look for evidence of pooling secretions, blood, or cyanosis. Unlike complications from other airway emergencies, trauma can possibly affect the anatomy of the airway Look for signs of facial injury that may obstruct the airway. Evaluation of the neck is also key as there can be compromise of the larynx and trachea in cases of laryngeal fracture or expanding hematoma from a neck injury. Also a brief evaluation of the patient’s mental state is important to ensure there is no potential airway compromise. A diminished mental state may be an indication for early airway intervention. As with other critically ill patients frequent re-evaluation is important.

There are several interventions that may be used depending on the level of airway compromise ranging from simple airway manipulation to endotracheal intubation and possible cricothyroidotomy. It is important to always maintain cervical spine immobilization due to the possibility of cervical spine injury. Consider performing jaw thrust and chin lift to establish patency of the airway. You should avoid placing a nasal airway if there is suspicion of a basilar skull fracture. Early identification of neck landmarks for cricothyroidotomy should the need arise. Assess the trachea for lateral deviation which may be a sign of tension pneumothorax.

B - Breathing

Breathing should be assessed simultaneously to the airway. What is the status of the patients breathing? Is the breathing rate and quality sufficient to maintain ventilation and perfusion? Are the breaths labored, shallow or is there paradoxical movement of the chest wall?

A patent airway DOES NOT mean adequate ventilation! Ventilation requires adequately functioning lungs, chest wall, and diaphragm to produce the depth and rate of respiration as well as the appropriate gas exchange. During a more detailed secondary survey, a detailed physical exam can assist in diagnosis of many conditions.

Take into account the work of breathing and quality of breathing. Accessory muscle usage can be seen with pain, pulmonary contusions, closed head injury, and diaphragmatic injury. This can be an early predictor of respiratory failure. This is usually not sustainable and will often result in respiratory failure. Listen for stridor which is a sign of upper airway obstruction. This may be heard in patients with smoke inhalation, blunt, or penetrating neck trauma. Also, listen for presence of breath sounds. Lack of breath sounds can suggest pneumo- or hemothorax. Breath sounds are insensitive for these diagnoses and therefore one should consider CXR or ultrasound for diagnosis.

C - Circulation

Circulation can be assessed in several ways including physical exam findings (such as peripheral pulses) and on cardiac monitoring (ie: blood pressure, pulse oximetry).

Evaluation of circulation can give quick information about a patient’s perfusion of vital organs and extremities. Typically abnormalities in circulation are related to either hypovolemic shock related to hemorrhage or direct compromise of the vascular structures related to the traumatic injury. Identifying the cause of the patient’s shock is key in understanding how treatments should progress. For example a patient with penetrating chest trauma can have multiple etiologies of shock such as cardiac tamponade causing cardiogenic shock or hemorrhagic shock related to acute blood loss from the wound. Bleeding should be controlled by direct pressure where possible or application of a tourniquet if direct pressure cannot applied. Head wounds can bleed excessively and hemostasis needs to be obtained quickly. Keep in mind to evaluate pulses in extremities that have obvious deformity. Anatomical realignment should be undertaken if there is any pulse deficit to ensure perfusion of distal tissue.

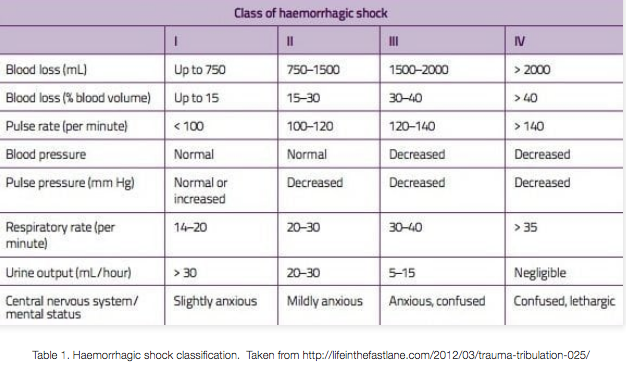

Interventions for circulation problems include administration of IV crystalloid or blood products. Early administration of blood products in the trauma patient with obvious injuries can help to improve circulation abnormalities. Most trauma centers have develop mass transfusion protocols (MTPs) to ensure that there is an adequate supply of blood products for trauma patients with injuries necessitating transfusion. Patients requiring large amounts of blood product infusion may benefit from placement of either bilateral large-bore IV in antecubital fossae or placement of a large bore central venous access catheter such as a Cordis. This type of access allows for rapid transfusion as well as warming of the blood products. The following table is a good reference for the degree of shock based on the amount of blood lost.

Found at https://litfl.com/trauma-major-haemorrhage/ - used under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

D - Disability

Disability evaluation will often come after a primary survey and is included within the secondary survey. Within evaluating for disability you should evaluate the patient’s mental status. Are they awake, alert, oriented and interactive? Have they suffered a head injury that is making them altered?

Since many traumas are a result of intoxication it is important to take this into consideration about the patient’s emergency department course. Calculation of a Glasgow-Coma Scale (GCS) is a good system to use in determining a person’s disability and can easily be trended over time. Since a patient’s mental status can affect their ability to protect their airway, any depression in the patient’s mental state may be an indication for early intubation and airway management. Below is a table with each area of the GCS. Remember that the GCS can never be 0!

Table 1: Glasgow-Coma Scale (GCS)

In evaluating a patient’s disability, it is important to do a focused neurologic exam. Evaluation of cranial nerves, motor nerves and sensory will help to determine further diagnostic testing or intervention. In patients with obvious deformity of a limb this can be especially important as it may require more timely intervention.

E - Exposure/Environmental

To complete the evaluation of a trauma patient it is important to fully detail any possible injuries that the patient has. This requires complete exposure of the patient. This practice will prevent you from missing injuries.

In any patient with penetrating trauma it is especially important to check both axilla, groin and gluteal folds. Once you have evaluated the patient it is important to then keep the patient covered and warm. Typically rooms used for trauma have a higher ambient temperature to prevent cooling of the patient. Also during the exposure phase, decontamination of the patient can take place. This can be important for patients that may have been exposed to chemicals or other potential hazardous materials. A patient should be thoroughly decontaminated for the safety of the patient and the emergency department team.

Both primary and secondary survey’s should occur succinctly and regimented. Following the same pattern for your evaluation will make it less likely that you are going to overlook key physical findings or other traumatic injuries. During the initial evaluation any interventions to stabilize the patient should be undertaken immediately. In general stabilization should occur before the patient leaves the trauma room. Sending an unstable patient for advanced imaging or other procedures without stabilization can be life threatening. If the patient is unstable and requires surgical intervention, they should proceed directly to an operating room under the care of a designated trauma surgeon. Table 2 provides a list of some of the potentially life and limb threatening conditions related to trauma.

Table 2. Potential Life or Limb Threatening Etiologies related to Trauma

Diagnostic Testing

Diagnostic testing should be dependent on the condition of the patient, suspected injuries based on the mechanism of the trauma and physical exam findings. In the general sense for critically ill patients labs that can be obtained quickly will be of largest benefit. Many hospitals and most trauma centers are going to have the ability to perform rapid bedside point of care testing for chemistry panels. These test can quick evaluate key chemistry findings. However there are varying degrees of accuracy typically in values that are vastly out of reference range (ie: too high or too low). Type and cross is another important lab in trauma patient. Fully cross-matched blood is preferable but has about 1-hour processing time. Trauma blood may be required for critical patients. Typically O Negative (males may receive O Positive blood) is used. Many centers will have this blood readily available near a trauma room. Other labs include:

- CBC (do not depend on Hgb to show bleeding immediately)

- Blood chemistry panel

- UA (microscopic hematuria common and not reliable for renal injury)

- Pregnancy test

- Blood gas

- Ethanol and drug Screen

- Coagulation studies

Plain film x-rays are another frequently used test of choice because they can be quickly accessed and interpreted, often at the patient’s bedside. Most frequently these films are limited to chest and pelvis imaging as part of the primary survey. Classically cervical spine films were used for quick evaluation, however due to limited ability to detect all fractures these have largely been replaced with CT imaging. If there is concern for pelvic trauma then an AP Pelvis x-ray may also be helpful in initial diagnostic imaging.

CT imaging has become the mainstay of trauma imaging. The mechanism of injury physical exam findings will ultimately determine what imaging should be done. Most imaging of the chest/abdomen/pelvis are going to be done using contrast to help diagnosis of injury. CT of the head and cervical spine are typically done without contrast. Additional imaging studies of the neck vasculature are going to be done with contrast to identify any potential vessel imagining. As was stated previously, the patient should be stabilized prior to attempting to obtain advanced imaging.

FAST (Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma) is an extremely helpful test for assessing patients who are unstable or have dangerous mechanisms. A full discussion on FAST exams can be found in other chapters. FAST is a tool to rapidly assess possible causes of hypotension in trauma patients.

Treatment

Emergency Department treatment of the trauma patient is going to focus on stabilizing the patient and treating the findings from testing. Given the wide breadth of possible injuries it is not prudent to discuss all treatment in this section. Definitive treatment for trauma patient is ultimately going to depending on the injuries that are diagnosed. Multi-system trauma patients are typically going to be admitted by a trauma service or a trauma surgeon for management of injuries or observation. Consultant services are also likely to be involved as well. Additional specific treatment items are located in specific trauma chapters.

Pearls and Pitfalls

- Trauma is a common problem, especially in relatively young patients.

- Trauma has high associated life years lost.

- Have an organized approach to assessing and managing trauma patients.

- Start with ABCDE and return to these anytime patient status changes.

- Perform a comprehensive organized secondary survey to evaluate patient and minimize risk of missing injury.

- Treat life and limb threats as you discover them

- Many traumatic injuries have subtle findings and require a high index of suspicion.

- Blood pressure will remain normal until class 3 hemorrhagic shock; use the whole clinical picture not just the numbers to guide your management.

- Move quickly to administer blood products and active massive transfusion protocols in patients presenting in hemorrhagic shock.

- Stabilize and transfer trauma patients to a trauma center as soon as possible.

Case Study

47-year-old male unrestrained driver ejected 15 feet from car then arrives via EMS. Vital Signs: 100/40, RR 28, HR110. Initially combative at the scene, but now difficult to arouse. He does not open his eyes, withdrawals only to pain, and makes gurgling sounds. EMS placed a c-collar and backboard, but could not start an IV.

As you move the patient over to the gurney, you notice tracheal deviation, paradoxical chest movement, and a large boggy right parietal scalp hematoma.

What do you do first?

Follow, “ABC’s, IV, O2, Monitor” as you tend to the patient’s primary survey.

- A: Is Airway intact? No, patient needs to be intubated with inline stabilization as he is altered and combative.

- B: Is Breathing intact? No, gurgling breath sounds with increased respiratory rate and tracheal deviation. This patient needs a needle decompression followed by a chest tube.

- C: Are there signs of shock? Yes, tachycardia and hypotension with altered mental status. These resolved when you placed the chest tube.

- D: What is the GCS? Eyes closed (1), withdraws only to pain (4), makes incomprehensible sounds (2) = total of 7. Less than 8, intubate!

- E: Upon exposure you see a cold, blue right foot. You reduce the foot to regain pulses.

Next you perform a Secondary Survey:

- HEENT: large boggy right parietal scalp, the pupils are sluggish and there’s hemotympanum on the right side. There is no facial trauma. The trachea is also deviated to the left.

- Chest: Absent breath sounds on right

- Heart: Tachycardic

- Abdomen: Soft, no guarding, no obvious tenderness

- Extremities: Left ankle open, dislocated cold, no pulse

- Neck/Back: normal

Start resuscitation with 2 liters IV normal saline, order type and cross, CBC, BMP, Urinalysis, and coagulation studies. Noting the tracheal deviation to the left and decreased breath sounds on the right, you quickly perform a needle decompression and place a chest tube. Portable chest x-ray reveals a resolving right sided simple pneumothorax (PTX). Pelvis x-ray is negative. FAST exam is negative.

You order antibiotics, tetanus booster and call orthopedic surgery. When the patient is stabilized you move to CT scan where the following scans are obtained: CT of the head, c-spine, chest, abdomen and pelvis.

The rest of his scans reveal the resolved pneumothorax and chest tube you placed, several broken ribs on the right, no visceral injuries and no pelvic trauma. He is taken emergently to the OR for treatment of his epidural hematoma as well as washout of his open ankle fracture/dislocation.

He spends several days in the SICU with an excellent hospital course, is extubated, and has normal neurological function. His chest tube is pulled, and he is discharged home in excellent condition.

References

- https://www.east.org/education/practice-management-guidelines/damage-control-resuscitation-in-patients-with-severe-traumatic-hemorrhage

- https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/quality%20programs/trauma/ntdb/ntdb%20annual%20report%202016.ashx

- Inaba K, Ives C, McClure K, et al. Radiologic evaluation of alternative sites for needle decompression of tension pneumothorax. Arch Surg. 2012;147(9):813-818.

- http://lifeinthefastlane.com/2012/03/trauma-tribulation-025/

- https://radiopaedia.org/articles/focussed-assessment-with-sonography-for-trauma-fast-scan