Pericardial effusion

Author Credentials

Authors: Michelle Haimowitz, MD, FAAEM Fellow, Advanced Emergency Medicine Ultrasonography Fellowship Department of Emergency Medicine, The Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University

Ryan C. Gibbons, MD, FAAEM, FACEP, FAIUM Director, Advanced Emergency Medicine Ultrasonography Fellowship, Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine Director, Ultrasound in Medical Education, The Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University

Editor: Eric Shappell, MD, MHPE Associate Director, MGH/BWH Harvard-Affiliated Emergency Medicine Residency, Department of Emergency Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital / Harvard Medical School

Updated: 2023

Case Study

A 68-year-old male with a history of metastatic lung cancer, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, presents with gradual onset shortness of breath and a positional, non-radiating, and non-exertional chest pain. The patient’s vital signs are: temperature of 98.6°F, pulse of 110 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 20 per minute, blood pressure of 100/60mm Hg and an oxygen saturation of 94% on room air. An ECG, chest x-ray, and labs are obtained. Your medical student asks you if there is any way that point of care ultrasound could be helpful in further evaluating this patient while you are walking to get the ultrasound machine.

Objectives

By the end of this module, the student will be able to:

- Understand the role of cardiac point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS), also known as focused cardiac ultrasound (FOCUS)

- Identify and describe the anatomy of the heart and pericardium

- Understand bedside ultrasound techniques to evaluate the heart and pericardium

- Identify and classify pericardial effusions

- Differentiate pericardial effusions from pleural effusions

- Recognize tamponade physiology

- Describe challenges and limitations of bedside ultrasound or POCUS

- Describe the appropriate ED population who would benefit from FOCUS

Introduction

“In the emergency department, focused cardiac ultrasound has become a fundamental tool to expedite the diagnostic evaluation of the patient at the bedside and to initiate emergent treatment and triage decisions by the emergency physician.” (Ref.23)

Emergency medicine providers have been utilizing focused cardiac ultrasound (FOCUS) for nearly thirty years. (Ref.16,31,36,37,56) While similar in practice and theory, FOCUS differs from comprehensive echocardiography.(Ref.46) As with most point-of-care ultrasound applications, focused transthoracic cardiac ultrasound is a goal-directed assessment of a symptomatic patient employed to answer specific clinical questions and serves as an adjunct to the physical exam. (Ref. 46,55) It is a rapid, safe and effective means to not only diagnosis numerous cardiac pathologies, but expedite treatment as well. In 2001, the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) endorsed focused echocardiography as a fundamental skill for the emergency provider. (Ref.1) Since that time, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has mandated emergency medicine residency programs provide ultrasound training in eleven core applications.

Table 1 illustrates many of the basic and advanced applications of cardiac ultrasound. This discussion will focus solely on pericardial effusions. Echocardiography remains the diagnostic study of choice for the detection and evaluation of pericardial effusions. (Ref. 2) In fact, as of 2003 the AHA/ACC/ASE have a level 1 recommendation for the use of echocardiography in the evaluation of all pericardial disease. (Ref. 10) It not only provides qualitative and quantitative information, but also enables assessment of the patient’s hemodynamic status and possible need for pericardiocentesis. (Ref. 2,33,40)

The Five E’s of Echo (Ref. 21) |

|

*Typical size ratio RV:LV is 0.6: 1.021

Table. 1 Roles of Focused Cardiac Ultrasound (FOCUS).

The pericardium is a hyperechoic sac which surrounds the heart and great vessels consisting of an outer fibrous parietal layer and inner serous visceral layer also known as the epicardium. (Ref. 2,40) Normally, a small amount of physiologic fluid (5-50ml) surrounds the heart to assist in function and protect against infection. (Ref. 2,18,40,55) With uncomplicated pericardial effusions, excess fluid initially accumulates in the most dependent areas, typically posteriorly and inferiorly around the right atrium which is normally the chamber with the lowest pressure. (Ref.13) Effusions rarely accumulate only anteriorly without a history of prior scarring or cardiac surgery. (Ref.18)

Pericardial effusions fall on a spectrum from asymptomatic to severe hemodynamic compromise. Effusions develop gradually or acutely depending on the clinical scenario. (Ref. 18,47) Etiologies are numerous as are their classifications. Tables 2 and 3 provide a brief overview of pericardial effusion classifications and causes, respectively.

Classification of Pericardial Effusion | ||||

Size (mm)* | Composition | Onset (weeks) | Distribution* | Definition |

<10 small | transudative | <1 (acute) | circumferential | simple |

10-20 moderate | exudative | <12 (subacute) | focal | complex |

>20 large | >12 (chronic) | |||

*Measured at end-diastole using visual estimation or M-mode. Trace physiologic fluid <50cc is within normal limits. (Ref.2,8,19,21,49) Others define effusion size as follows (in mm)27: <10, 10-15, > (Ref.15). Multiple cardiac views are utilized to assess for focal effusions (Ref. 8,11,21)

Table 2. Pericardial Effusion Classifications. (Ref.12)

Causes of Pericardial Effusions | |

Common | Less Common |

|

|

Table 3. Causes of Pericardial Effusion (Ref.2,8,18,26,40-42,49)

Initial Actions and Primary Survey

As with any emergent condition, the following should be performed:

- Prioritize the ABCs.

- Insert 2 large bore IVs.

- Place the patient on the monitor.

If there is concern for cardiac tamponade, the following steps should alse be performed:

- Perform a focused history and physical while performing a cardiac POCUS examination.

- An ECG and a portable chest x-ray should be obtained.

In hemodynamically unstable patients, administer intravenous fluids and prepare for an emergent pericardiocentesis. Cardiology or cardiothoracic surgery should be consulted to discuss procedural options for drainage including

pericardiocentesis at bedside or in the catheterization lab, in addition to surgical drainage. Be cautious with mechanical ventilation as positive airway pressure reduces preload, worsening the patient’s hemodynamics. In patients with

refractory hypotension, start vasopressors. If there are no contraindications, perform an emergency pericardiocentesis on cardiac arrest or hemodynamically unstable patients with a pericardial effusion and concern for tamponade.

Presentation

Tables 4-6 review the risk factors, signs & symptoms, and classic ECG & chest x-ray findings in patients with pericardial effusions that may warrant a focused cardiac ultrasound to assess for a pericardial effusion, cardiac tamponade, or other cardiac pathology.

Risk Factors for Pericardial Effusions | |

|

|

Table 4. Risk Factors for Pericardial Effusions.

Signs and Symptoms of Pericardial Effusions | |

Symptoms | Signs |

Undifferentiated

Nonspecific/Constitutional

|

|

*Venous distention with inspiration (JVD) **Patients with chronic hypertension may not exhibit hypotension. ***Aortic dissection is associated with pericardial effusions; pericardial effusion may be the only visible sign aortic dissection on FOCUS.

Table 5. Signs and Symptoms of Pericardial Effusions.

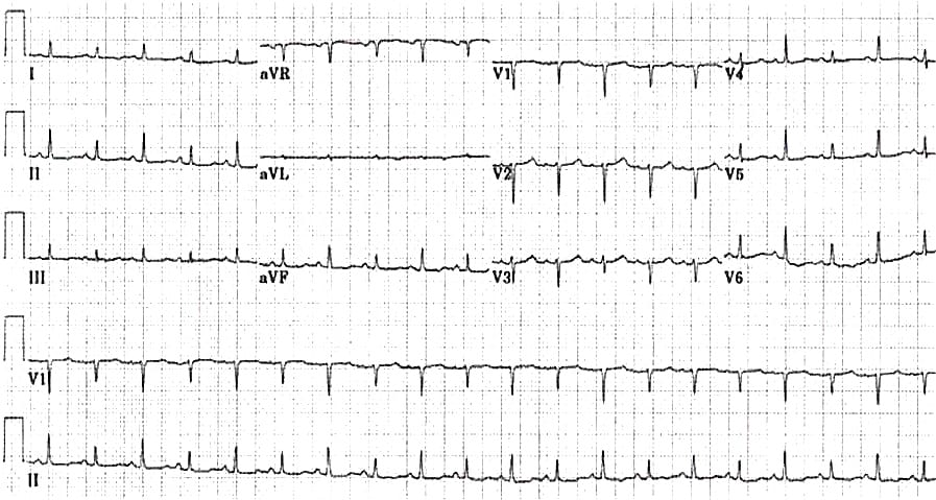

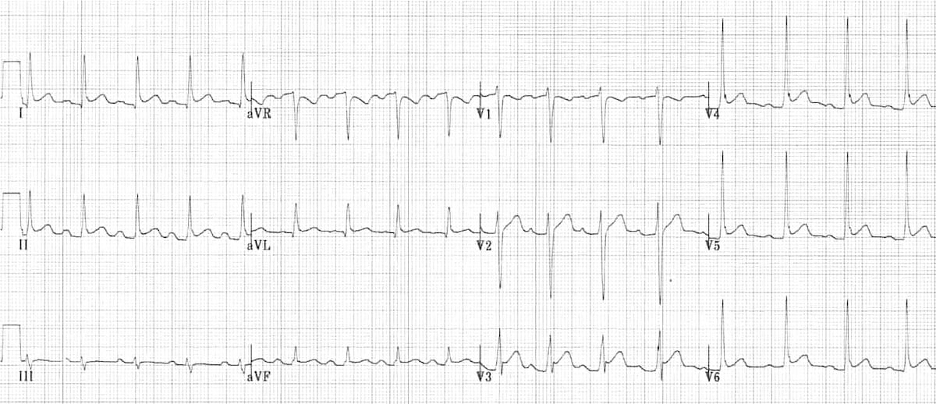

Classic ECG and Chest X-ray Findings of Pericardial Effusion | |

ECG (Ref.47) | Chest X-ray |

|

|

Table 6. Classic ECG and Chest X-ray findings of pericardial effusions.

Image 1. EKG findings of a massive pericardial effusion. Please note the low QRS voltage and varying amplitudes of the QRS complex (electrical alternans). Image courtesy of Life in the Fast Lane. Used with permission based on Creative Commons Attribution License (notations added). Original image location: https://litfl.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/ECG_massive_pericardial_effusion.jpg.

Image 2. ECG Findings of Pericarditis. Please note the diffuse ST elevations, the PR depressions, the down-sloping TP segments, and the ST depression in AVR. The image is used courtesy of Life in the Fast Lane based on the Creative Commons Attribution License. The original image is located at: ECG-Pericarditis-3.jpg (1200×518) (litfl.com).

Image 3. Enlarged Cardiac Silhouette. An enlarged cardiac silhouette can be a sign of a pericardial effusion. Used with permission of Drs Thomas G. Costantino and Ryan C. Gibbons at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University

Diagnostic Testing

Chest x-ray and ECG serve as adjuncts when assessing patients for pericardial effusions, but neither are diagnostic. Ultrasound is a readily accessible bedside tool that can quickly and accurately diagnose pericardial effusions and cardiac tamponade.

Point-of-Care Ultrasound Technique (Ref.21,27,49,55)

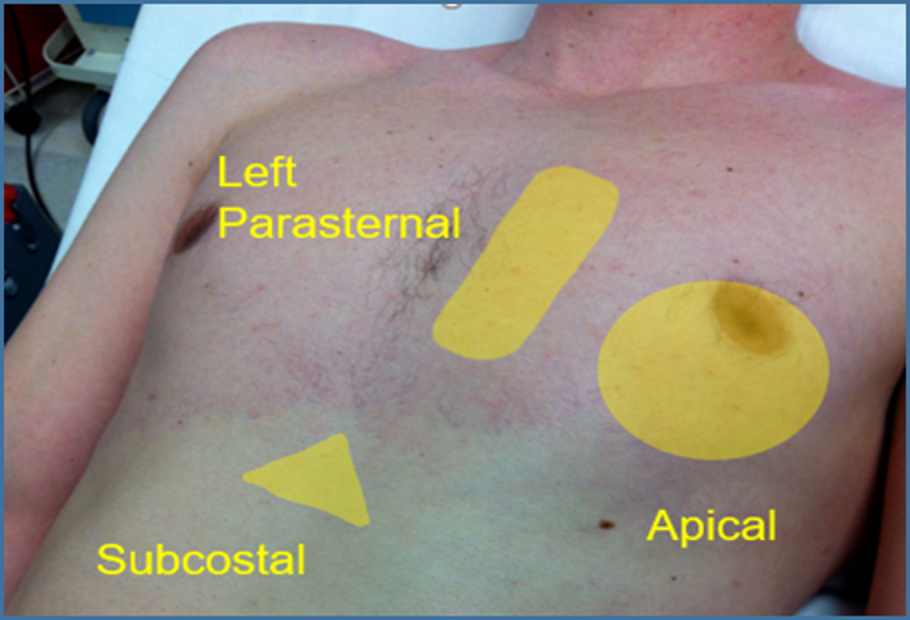

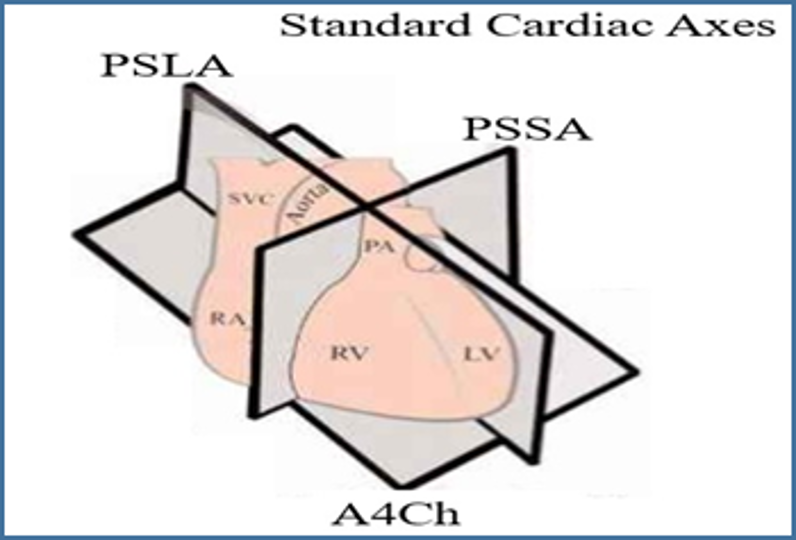

Imaging of the heart is done in real time. The 1-5 mHz phased array (cardiac) probe (Image 4) is routinely utilized given its small footprint which augments intercostal imaging. (Ref.27) Hold the probe similar to a pencil resting your hypothenar eminence on the chest wall, which allows better manipulation of the probe. Typically, there are four standard cardiac views:

- Parasternal long axis (PSLA or PLAX)

- Parasternal short axis (PSSA or PSAX),

- Apical four chamber (A4Ch)

- Subcostal or subxiphoid. (Ref.21,49,55)

There are additional advanced views & applications beyond the scope of this review.

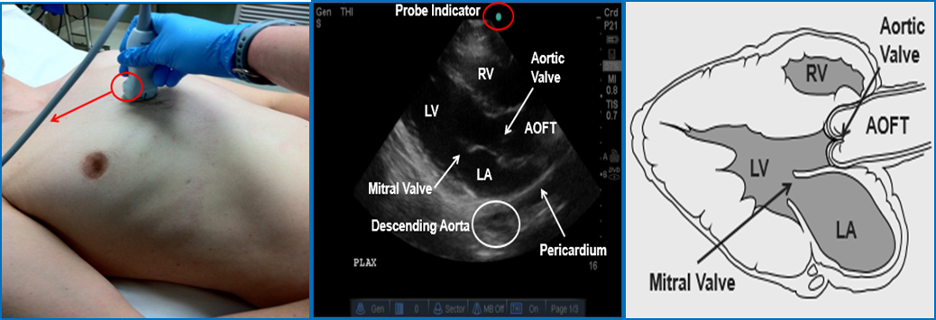

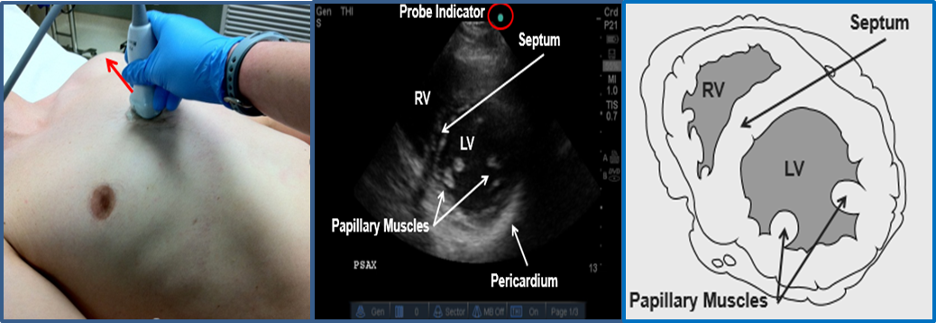

To begin, place the probe along the left parasternal border in the 2nd through 5th intercostal space. Traditionally, the probe indicator (circled in Image 4) is oriented to the patient’s right shoulder to obtain the PSLA view. Rotate the probe 90° clockwise to acquire the PSSA image. Maintain the indicator’s alignment towards the left shoulder or axilla while sliding in the direction of the cardiac apex or PMI (point of maximum impulse) to visualize the A4Ch, which is typically along the left lateral chest wall in the 5th intercostal space inferolateral to the nipple. Have female patients lift their breasts to improve imaging. Flatten your angle to optimize your A4Ch view. You may need to position your hand over the probe to achieve the appropriate angle. Place the patient in the left lateral decubitus position to augment the A4Ch view as well.

Image 4. Phased Array (cardiac) probe. Used with permission of Drs Thomas G. Costantino and Ryan C. Gibbons at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University

Image 5. Standard Cardiac Windows. The image above shows the ultrasound probe can be placed to obtain the standard cardiac views.

Used with permission of Drs Thomas G. Costantino and Ryan C. Gibbons at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University

Below is a list of what some of the standard cardiac views can effectively visualize:

- Parasternal long axis: pericardial effusions, the aortic outflow tract

- Parasternal short axis: ideal for assessing global cardiac function

- Apical four-chamber: can be helpful for pericardiocentesis

- Subcostal: pericardial effusions and assessing global cardiac function

Image 6. Standard Cardiac Axes. Used with permission of Drs Thomas G. Costantino and Ryan C. Gibbons at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University.

Image 7. Cardiac Axes. Image courtesy of Barnard Health. Used under the Creative Commons License 3.0 (http://www.barnardhealth.us/about/). Original image located at: http://www.barnardhealth.us/echocardiography/info-bvs.html.

Parasternal Long Axis (PSLA) View

Image 8 Parasternal Long Axis (PSLA) View. Left Ventricle (LV); Right Ventricle (RV); Left Atrium (LA); Aortic Outflow Tract (AOFT). Used with permission of Drs Thomas G. Costantino and Ryan C. Gibbons at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University.

Video 1: PSLA normal

Video 2: PSLA with effusion

Parasternal Short Axis (PSSA) View

Image 9. Parasternal Short Axis (PSSA) View. Used with permission of Drs Thomas G. Costantino and Ryan C. Gibbons at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University.

Video 3: PSSA normal

Video 4: PSSA with effusion

Apical 4-Chamber (A4Ch) View

Image 10 Apical Four Chamber (A4Ch) View. Used with permission of Drs Thomas G. Costantino and Ryan C. Gibbons at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University.

Video 5: A4Ch normal

Video 6: A4Ch with effusion

The subcostal view is typically the easiest and most reliable at detecting pericardial effusions since the most dependent portion of the heart is nearest to your probe. (Ref.21) Additionally, it is often the best view to distinguish between pleural and pericardial effusions since there is no pleural reflection between the liver and the heart. (Ref. 49,55) Either the phased array or curvilinear (abdominal) probe (image 11) can be utilized to obtain the subcostal view. Use an overhand grip to allow for a shallow approach of 5-15°. Having the patient inhale deeply will bring the heart closer to the probe. Use the liver as your acoustic window and be sure to adjust your depth to visualize the entire heart.

When using the curvilinear probe, the indicator is positioned to the patient’s right, the traditional point of care ultrasound orientation, using the abdominal setting.

Image 11. Curvilinear (abdominal) probe. Used with permission of Drs Thomas G. Costantino and Ryan C. Gibbons at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University.

Subxiphoid View

Image 13. Subcostal View. Phased Array (cardiac) probe. Used with permission of Drs. Thomas G. Costantino and Ryan C. Gibbons at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University.

Video 7: Normal Subxiphoid View

Video 8: Subxiphoid View with Effusion

Focused cardiac ultrasound is the diagnostic study of choice for identifying pericardial effusions. (Ref.1,2,10,23,46,54) It can detect as little as 15-35cc of pericardial fluid. (Ref.8,56) Echocardiography can help clarify the type and extent of the effusion, as well as recognize tamponade physiology and guide treatment through pericardiocentesis. An uncomplicated effusion appears as an anechoic stripe separating the heart from the parietal pericardium, initially accumulating dependently in the posterolateral and inferior sections.(Ref.27,49) Complex effusions, such as infectious or traumatic, can appear echogenic with internal echoes or septations and may collect circumferentially or focally. The size or amount of effusion is visually estimated or measured using M-mode at end-diastole. (Ref.18,19)

Overall, studies have demonstrated excellent sensitivities and specificities from 96-100% for the detection of pericardial effusions in both medical and trauma patients using focused cardiac ultrasound. (Ref.1,23,28,36,37,50,51) Plummer, et al. not only demonstrated remarkable sensitivity, but also a decreased time to the operating room (OR) from 42 to 15 minutes and an improved survival rate from 57% to 100% in patients with penetrating chest trauma with the diagnosis of traumatic pericardial effusions on bedside ultrasound. (Ref.36,37) Tayal, et al. showed survival benefit as well in patients with non-traumatic PEA (pulseless electrical activity) arrest with a bedside ultrasound diagnosis of a pericardial effusion.

Technical Considerations

As with any ultrasound study, proper set up is key to obtaining accurate images. The patient should be placed in the supine position at the level of the scanner’s waist with the head of the bed slightly raised to 30°. Dim the lights as appropriate and apply adequate ultrasound gel, especially with the subcostal view to maintain suitable contact between the probe and skin.

Utilize the cardiac presets when scanning the heart. Modify the gain, frequency, and depth to refine your images. The initial depth should be maximized in order to display the entire heart, including the posterior pericardium. Adequate depth is particularly important with the subxiphoid window. Once the entire heart is visualized, the depth can be adjusted accordingly to optimize your view.

Have the patient lie in the left lateral decubitus position to enhance imaging, especially for the A4Ch. Nonetheless, up to 25-30% of patients will not have an adequate A4Ch window. In these patients, it can be helpful to utilize a different cardiac view or use advanced imaging such as transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), CT, or cardiac MRI.

Cardiac Tamponade

All individuals with pericardial effusions are at risk of developing tamponade, which is a potentially fatal complication resulting in obstructive shock. The diagnosis is challenging to all physicians given that the signs and symptoms of both pericardial effusions and cardiac tamponade can be subtle and not always present. (Ref.6,25) Many patients with pericardial effusions are asymptomatic or have nonspecific signs and symptoms, such as cough, fever, hiccups, fatigue, and abnormal vital signs (see Table 5). Moreover, traditionally we are taught that tamponade is a clinical diagnosis and that patients will demonstrate the classic Beck’s triad of hypotension; muffled, distant heart sounds; and jugular venous distension (JVD).4 In reality though, this is a relatively rare and late finding. (Ref.6,49,14,20,25,28) Less than 10-40% patients will present with this triad. (Ref.14,40,38,49,56) Furthermore, medical patients will rarely present this way given the chronicity of their diseases. Trauma patients are much more likely to depict Beck’s triad, although our clinical suspicion is already much higher in this subset of individuals.

Pulsus paradoxus, defined as a >10 mmHg drop in systolic blood pressure (SBP) with inspiration, can be useful in diagnosing cardiac tamponade. However, assessing for this can be time consuming and difficult with an unstable patient. Frequently, it is not present with significant hypovolemia. Furthermore, it is seen in numerous other conditions, such as emphysema, pulmonary embolism, congestive heart failure, mitral stenosis, aortic regurgitation, and in other forms of shock. (Ref. 2,8,9,20,24,40,47)

Given the nonspecific complaints and unreliable exam findings, cardiac tamponade is not just a clinical diagnosis. Utilize FOCUS in conjunction with lung and inferior vena cava (IVC) ultrasound as an adjunct to the physical exam to assess for causes of obstructive shock, such as tamponade, aortic dissection, and tension pneumothorax. (Ref.17)

Cardiac tamponade occurs along a spectrum of hemodynamic changes when intrapericardial pressure exceeds intracardiac pressure causing impaired filling, chamber collapse, and decreased cardiac output (CO). (Ref. 8,47) This is a form of obstructive shock. The most important factor in developing tamponade physiology is the rate of effusion build up rather than its size. (Ref.8,9,18,19,40) Gradual accumulation, seen commonly with chronic medical conditions, allows the pericardium to accommodate large volumes in excess of 1-2 liters. Several non-traumatic effusions are more likely to develop tamponade though, including those caused by bacterial infections, neoplasms, and post-radiation. Nearly 1/3 of chronic large effusions regardless of etiology progress to obstructive shock. (Ref.18,19)

Image 14 Tamponade Pathophysiology (Ref.47). From the New England Journal of Medicine, Spodick D, Acute cardiac tamponade, 349, 684-90. Copyright © 2003 Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission from Massachusetts Medical Society.

Traumatic effusions accrue rapidly preventing the pericardium to adapt. (Ref.40) Subsequently, cardiac tamponade occurs in these situations with as little as 50-100cc of fluid. (Ref.45) The pericardial compliance determines the amount of fluid which triggers tamponade. Dr. David Spodick described tamponade as a “last-drop” phenomenon: “the final increment produces critical cardiac compression, and the first decrement during drainage produces the largest relative decompression”(see Image 14). (Ref.47) Tables 7 and 8 review the common causes of tamponade as well as the characteristic ultrasound findings.

Causes of Tamponade | |

Common | Less Common |

|

|

Table 7. Causes of Tamponade (Ref.2,18,19)

Ultrasound Findings in Tamponade | |

Right ventricular collapse

Right atrial collapse (Ref. 9,18,19,22,47)

Inferior vena cava plethora** (Ref. 17-19)

| Large effusion

Left atrial collapse (Ref. 8)

Left ventricular collapse (Ref.8,27,33,45,47)

|

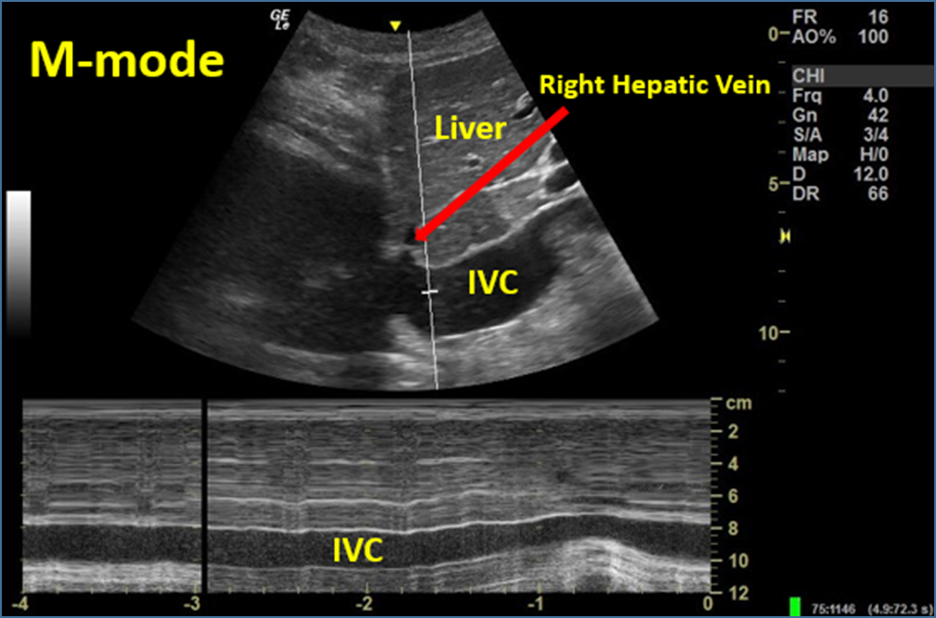

*Right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) **Visual estimation or measured with M-mode about 2-3cm distal from its entrance into the right atrium or just distal to where the right hepatic vein joins the IVC (see image 11).

Table 8. Ultrasound Findings in Tamponade (Ref.15,39) (see videos 9-12 & Images 15-18).

Ultrasound findings suggestive of cardiac tamponade

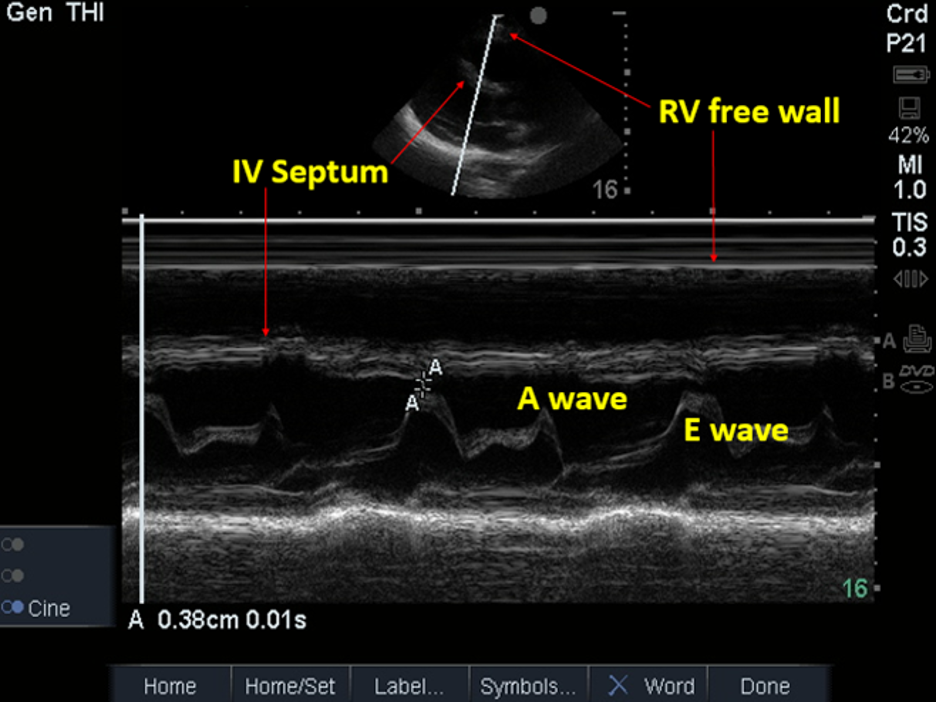

Pathologic ventricular chamber collapse occurs during ventricular diastole (atrial systole), whereas pathologic atrial collapse occurs during ventricular systole (atrial diastole). Utilize M-mode

in the PSLA or subxiphoid view to help identify diastole by correlating with the peak E-wave amplitude or replay videos to identify when the mitral (PSLA or A4Ch view) and/or tricuspid (A4Ch view) valves are fully open (see

images 12-14). (Ref.21,33) Many of these ultrasound findings can be challenging to identify on FOCUS, therefore consider tamponade strongly if the patient is hypotensive with a pericardial effusion. (Ref. 33) Transvalvular pulsed

wave doppler inflow velocities are challenging even for advanced practitioners and routinely do not add much with respect to the diagnosis of tamponade pathology. (Ref.33) The pathophysiology and method to measure these values

are beyond the scope of this review.

Image 15. M-mode to Evaluate IVC Respirophasic Variation (complete lack of variation; IVC plethora). Used with permission of Drs Thomas G. Costantino and Ryan C. Gibbons at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University

Image 16. PSLA view; M-mode to Evaluate for RV Collapse during Ventricular Diastole (no collapse present). Used with permission of Drs Thomas G. Costantino and Ryan C. Gibbons at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University

Image 17. PSLA view; Ventricular Diastole without Evidence of Tamponade; Large Circumferential Effusion. Used with permission of Drs Thomas G. Costantino and Ryan C. Gibbons at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University.

Image 18. PSSA view; RV collapse during Ventricular Diastole; Large Circumferential Effusion. Used with permission of Drs Thomas G. Costantino and Ryan C. Gibbons at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University.

Videos of Cardiac Tamponade

Video 9: PSLA with large effusion & RV collapse consistent with tamponade physiology.

Video 10: PSSA with large effusion & RV collapse consistent with tamponade.

Video 11: Subcostal with large effusion and tamponade physiology.

Video 12: IVC plethora without respirophasic variation.

Video 13: A4Ch electrical alternans.

Video 14: PSLA electrical alternans.

Treatment

Treatment is based on the patient’s risk factors, size of the effusion, and hemodynamic stability. Consider discharge for low risk patients who are clinically stable and asymptomatic that do not have high risk features (e.g. recent cardiac procedure). For symptomatic patients or those with larger effusions, consider admission. Administer intravenous fluids to hemodynamically unstable patients. Consider vasopressors as well. However, these are temporizing measures. Consult cardiology or cardiothoracic surgery immediately and prepare for a bedside pericardiocentesis.

Pericardiocentesis

Emergent pericardiocentesis is a potentially life-saving procedure in the hemodynamically unstable patient. Unfortunately, it is a rare and risky procedure that few emergency physicians practice routinely. The potential complications are listed in Table 9.

Image 19. Pericardiocentesis with Ultrasound. Used with permission of Drs Thomas G. Costantino and Ryan C. Gibbons at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University.

Image 19. Pericardiocentesis with Ultrasound. Used with permission of Drs Thomas G. Costantino and Ryan C. Gibbons at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University.

Complications of Pericardiocentesis |

|

Table 9. Complications from Pericardiocentesis (Ref. 9,49,53)

Traditionally, we are taught to use the blind subcostal approach. However, Tsang et al. conducted a 20-year retrospective review at the Mayo clinic and demonstrated a 97% success rate with ultrasound guidance with substantially less complications. (Ref. 33,35,52,53) Furthermore, only 20% of the time was the subcostal approach the ideal one. Providers had far greater success with the A4Ch method.

Multiple views are advised to identify the optimal approach which is wherever the fluid is closest to the probe and where the lung is not in the way. The patient should be supine with the HOB slightly elevated. The left lateral decubitus position may improve your visualization as well. (Ref. 9) Intravenous fluids can be given while prepping for the procedure in an effort to augment cardiac output. Under sterile conditions, use a 16 or 18-gauge needle with ultrasound guidance to ensure its location within the pericardial sac. Once in position, use the Seldinger technique to place a catheter for continued drainage since there is a 30% recurrence rate. (Ref.52-53) Nagdev et al. described a novel in-plane technique via the PLSA. (Ref.32) Refer to the reference section below for a detailed review.

If the patient is hemodynamically stable, defer pericardiocentesis to the cardiologist or cardiothoracic surgeon.

Surgical evacuation is optimal though for posterior, nonuniform (loculated or focal), complex, and thrombosed effusions. (Ref. 9) Traumatic effusions are best managed with surgical intervention as well. (Ref. 51) An emergent pericardiocentesis can be a temporizing measure in the hemodynamically unstable patient without access to a cardiac catheterization lab or surgical specialties. (Ref. 56) In a cardiac arrest patient with an effusion, pericardiocentesis is immediately warranted.

Videos of Pericardiocentesis

Video 15: Needle tip visualized during pericardiocentesis

Video 16: Needle tip visualized during pericardiocentesis; CPR in progress

Pearls and Pitfalls

- Patient body habitus and stability, lung artifact, chest wall injuries, and ongoing procedures or resuscitation can obscure cardiac visualization. (Ref. 55)

- Be sure to utilize all four standard views and make subtle changes to your probe placement and orientation along with patient positioning to optimize your views through the intercostal spaces. Rotating, angling, and tilting your probe, as well as trying advanced views (as your training progresses), can facilitate your scans. (Ref. 55)

- Placing the patient’s left hand overhead may widen the intercostal spaces. (Ref. 27)

- Remember, patients’ anatomies vary. Adjust your probe placement as needed by sliding cranially and caudally along the left parasternal border between the 2nd and 5th intercostal spaces. Even moving to the right parasternal border may improve your images.

- It is important to note that if someone is hypotensive and has a pericardial effusion, the pericardial effusion may not be the etiology of the hypotension. Please check for other ultrasound findings of cardiac tamponade.

Maneuvers to Augment Cardiac Visualization | ||||

Parasternal long axis | Parasternal short axis | Apical 4 chamber | Subcostal | |

Inhale | X | |||

Exhale | X | X | X | |

Supine (HOB* 30° upright) | X | X | X | |

Left lateral decubitus | X | X | ||

*Head of bed

Table 10. Maneuvers to Augment Cardiac Visualization (Ref. 27)

Cardiac Anatomic Position in the Chest Cavity | ||||

Medial | Lateral | Higher | Lower | |

Younger | X | X | ||

Elderly | X | X | ||

Low BMI | X | |||

Obese | X | |||

*Body mass index

Table 11. Cardiac Anatomic Position in the Chest Cavity (Ref. 27)

- The apical four chamber (A4Ch) view is the most technically challenging one. Move the patient into the left lateral decubitus position to bring the heart closer to the chest wall in order to supplement your view. Nonetheless, 25-30% of individuals will not have a visible A4Ch view.

- Remember, only 10-40% of patients with cardiac tamponade will present with the classic Beck’s triad of distance, muffled heart sounds; jugular venous distension; and hypotension. Utilize FOCUS in conjunction with lung and IVC ultrasound to supplement your physical exam.

- Pulsus paradoxus is seen in numerous other conditions, such as emphysema, pulmonary embolism, congestion heart failure, mitral stenosis, and aortic regurgitation. It is often absent in severe hypovolemia.

- Rate of accumulation rather than size is the most important determinant of cardiac tamponade. Traumatic, neoplastic, infectious, and iatrogenic effusions are most likely to precipitate obstructive shock.

- Utilize all standard views (and non-standard) to avoid missing focal, loculated, and small effusions, which can all cause tamponade physiology. (Ref. 9,33,41-43)

False Positives and Negatives on POCUS for Pericardial Effusions | |

False Positives | False Negatives |

|

|

Table 12. Pericardial Effusions

POCUS False Positives and Negatives for Cardiac Tamponade | |

False Positive | False Negative |

Right heart collapse

*Inferior vena cava collapse | Lack of right heart collapse

|

Table 13. Cardiac Tamponade

- The anterior epicardial fat pad is a heterogeneous hypoechoic tissue with internal echoes that moves in conjunction with cardiac activity. (Ref. 9) It is not circumferential and not clinically significant. (Ref. 21) Normally, it is found in obese and elderly patients. (Ref. 8) The fat pad is best seen above the RVOT in the PSLA view. (Ref. 9) Again, employ multiple views to differentiate between the anterior fat pad and pericardial effusions. (Ref. 11) Loculated and focal effusions can be particularly challenging to distinguish from an epicardial fat pad. The latter normally will have no impact on the patient’s hemodynamic status whereas the former can cause hemodynamic compromise.

- Differentiating between pleural and pericardial effusions can be challenging. Identify the descending aorta in the PSLA view (see image 20). Pericardial effusions track along the heart and separate the aorta from the pericardium and cross the midline. Pleural effusions do not and will accumulate posterolateral to the descending aorta. Typically, effusions identified in the subcostal view will be pericardial given there is no pleural reflection between the heart and liver.49 Effusions posterolateral to the heart in the subxiphoid view are typically pleural whereas fluid between the liver and diaphragm is ascites. Look for the falciform ligament (see video 21) attached to the diaphragm and utilize multiple lung and abdominal views to help distinguish between these pathologic entities. Lung consolidation or collapsed lung from atelectasis may be seen as well to help identify a pleural effusion (see videos 17-21).

Videos of Pleural Effusions

Video 17: PSLA pleural effusion seen posterolateral to the heart; Small pericardial effusion

Video 18: PSSA with pleural effusion posterolateral to heart; Small pericardial effusion

Video 19: PSLA pleural effusion with lung consolidation; Small pericardial effusion

Video 20: Pleural effusion with lung collapse & spine sign in right hemithorax

Video 21: Ascites with visible falciform ligament

Image 20 Pericardial vs Pleural Effusion. Used with permission of Drs Thomas G. Costantino and Ryan C. Gibbons at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University.

- FOCUS findings in cardiac tamponade are challenging even for advanced practitioners. If the patient is hypotensive with an effusion, consider cardiac tamponade. Consult cardiology immediately and prepare for an emergent pericardiocentesis. Supplement IVF can help augment cardiac output as a temporizing measure. If the patient is hemodynamically stable, defer pericardiocentesis to the cardiologist. False positives can occur in the setting of hypovolemia where the right atrium collapses. However, in this setting the inferior vena cava will collapse as well, which is incredibly uncommon in tamponade. False negatives occur in the setting of chronically elevated right sided cardiac pressures.

- Surgical evacuation is optimal for posterior, nonuniform (loculated or focal), complex, and thrombosed effusions. (Ref. 9) Traumatic effusions are best managed with surgical intervention as well. An emergent pericardiocentesis can be a temporary measure in the hemodynamic unstable without access to a cardiac catheterization lab or surgical specialties. In the coding patient with an effusion, immediate pericardiocentesis is warranted with bedside ultrasound guidance ideally.

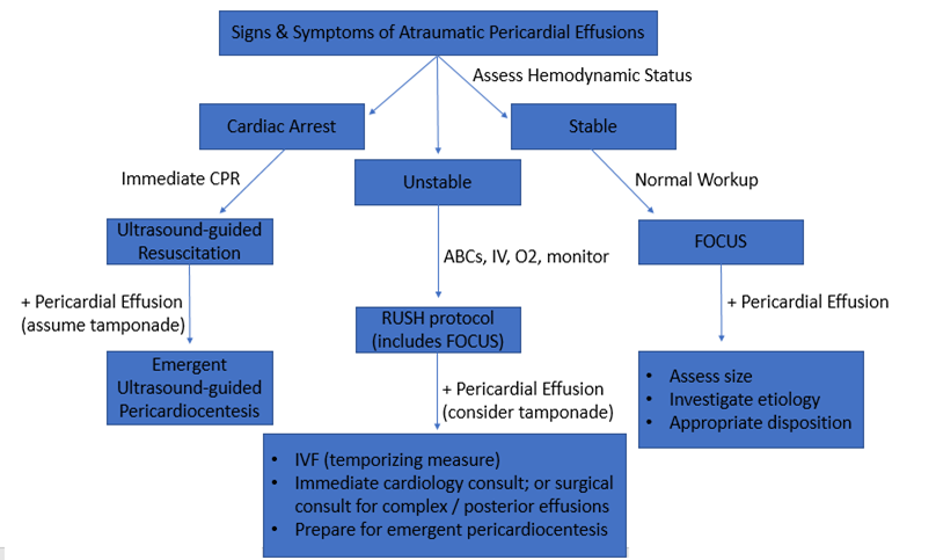

Diagnostic Approach

Image 21. Diagnostic Approach to atraumatic pericardial effusions.

Case Study Resolution

Point-of-care ultrasound visualized a large, circumferential pericardial effusion. The patient remained hemodynamically stable for an hour, and then suddenly decompensated, becoming altered with a blood pressure of 70/40. A repeat ultrasound was performed of the heart, which now demonstrated right ventricular collapse. An emergent pericardiocentesis was performed, after which the blood pressure improved to 110/60. The patient was admitted to the ICU and was evaluated by cardiothoracic surgery. The patient underwent surgical drainage and had an uncomplicated hospital course and was discharged from the hospital neuro-intact.

References

- American College of Emergency Physicians. Emergency ultrasound guidelines – 2008. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:550-70.

- Adler Y, et al (2015) ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J.

- Appleton C, et al. Cardiac tamponade and pericardial effusion: respiratory variation in transvalvular flow velocities studied by Doppler echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol, 11 (1988), pp. 1020–1030.

- Beck CS: Two cardiac compression triads. J Am Med Assoc. 1935; 104:714–6.

- Blaivis M. Incidence of pericardial effusion in patients presenting to the emergency department with unexplained dyspnea. Acad Emerg Med. 2001; 8:1143-46.

- Blaivis M, et al. Impending cardiac tamponade, an unseen danger? Am J Emerg Med. 2000; 18: 339–40.

- Burstow D, et al. Cardiac tamponade: characteristic Doppler observations. Mayo Clin Proc 1989; 64:312–24.

- Ceriani E, et al. Update on bedside ultrasound diagnosis of pericardial effusion. Internal and Emergency Medicine, 04/2016, Volume 11, Issue 3.

- Chandraratna P, et al. Role of echocardiography in the treatment of cardiac tamponade. 2014;31(7):899-910.

- Cheitlin M, et al. ACC/AHA/ASE 2003 guideline update for the clinical application of echocardiography: summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/ASE Committee to Update the 1997 Guidelines for the Clinical Application of Echocardiography). Circulation 2003; 108:1146–1162.

- Elavunkal J, et al. Emergency Ultrasound identification of loculated pericardial effusion: The importance of multiple views. Acad Emerg Med. 2011 18: e29.

- Armstrong W, et al. Feigenbaum’s Echocardiography, 7th ed..Philadelphia, 2010.

- Goodman A et al. The role of bedside ultrasound in the diagnosis of pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade. Journal of Emergencies, Trauma and Shock, 01/2012, Volume 5, Issue 1.

- Guberman B, et al. Cardiac tamponade in medical patients. Circulation. 1981;64:633–40.

- Guntheroth W. Sensitivity and specificity of echocardiographic evidence of tamponade: implications for ventricular interdependence and pulsus paradoxus. Pediatr Cardiol 2007 28:358–362.

- Hauser, A, et al. The Emerging Role of Echocardiography in the Emergency Department. Annals of EM 1989; 18: 1298-1303.

- Himelman R, et al: Inferior vena cava plethora with blunted respiratory response: A sensitive echocardiographic sign of cardiac tamponade. J Am Coll Cardiol 1988; 12:1470.

- Imazio M, et al. Management of pericardial effusion. Eur Heart J 2013; 34:1186–1197.

- Imazio M, et al. Triage and management of pericardial effusion. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2010; 11:928–935.

- Jacob S, et al. Pericardial effusion impending tamponade: a look beyond Beck's triad. Am J Emerg Med, 27 (2009), pp. 216–219.

- Kennedy Hall M, et al. The "5Es" of emergency physician-performed focused cardiac ultrasound: a protocol for rapid identification of effusion, ejection, equality, exit, and entrance. Acad Emerg Med. 2015 May;22(5):583-93.

- Kronzon I, et al. Diastolic Atrial Compression: A Sensitive Echocardiographic Sign of Cardiac Tamponade. JACC Vol. 2, No 4 October 1983,770-5.

- Labovitz A, et al. Focused cardiac ultrasound in the emergent setting: a consensus statement of the American Society of Echocardiography and American College of Emergency Physicians. J Am Soc Echo. 2010 Dec;23(12):1225-30.

- Leeman D, et al. Doppler echocardiography in cardiac tamponade: exaggerated respiratory variation in transvalvular blood flow velocity integrals. J Am Coll Cardiol, 11 (1988), pp. 572–578.

- Levine M, et al. Implications of echocardiographically assisted diagnosis of pericardial tamponade in contemporary medical patients: detection before hemodynamic embarrassment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991; 17: 59–65.

- Levy PY, et al. Etiologic diagnosis of 204 pericardial effusions. Medicine 2003; 82:385–391.

- Ma O, et al.Emergency Ultrasound, 3rdNew York, 2014.

- Mandavia D, et al. Bedside echocardiography by emergency physicians. Ann Emerg Med, 38 (2001), pp. 377–382.

- Materazzo C, et al. Respiratory changes in transvalvular flow velocities versus two-dimensional echocardiographic findings in the diagnosis of cardiac tamponade. Italian Heart Journal, 03/2003, Volume 4, Issue 3.

- Mayosi B, et al. Tuberculous pericarditis. Circulation 2005; 112:3608–16.

- Mayron R, et al. Echocardiography by emergency physicians: Impact on diagnosis and therapy. Ann Emerg Med. 1989; 17:150.

- Nagdev A, et al. A novel in-plane technique for ultrasound-guided pericardiocentesis. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(9): 1424.e5-9.11.

- Nagdev A, et al. Point of care ultrasound evaluation of pericardial effusions: Does this patient have cardiac tamponade? 2001 ;82(6): 671.

- Ntsekhe M, et al. Tuberculous pericarditis with and without HIV. Heart Fail Reviews 18.3 (2013): 367-373.

- Osranek, M et al. Hand-carried ultrasound-guided pericardiocentesis and thoracentesis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr, 16 (2003), pp. 1–7.

- Plummer D, et al. Emergency department echocardiography improves outcome in penetrating cardiac injury. Ann Emerg Med 1992; 21:709–12.

- Plummer D. Principles of emergency ultrasound and echocardiography. Ann Emerg Med. 1989; 18:1291–7.

- Qureshi, A, et al. Tamponade and the rule of Tens. Lancet 2008; 371:1810.

- Reydel B, et al. Frequency and significance of chamber collapses during cardiac tamponade. Am Heart J, 119 (1990), pp. 1160–1163.

- Roy C, et al. Does this patient with a pericardial effusion have cardiac tamponade? JAMA 2007; 297:1810-18.

- Sagrista-Sauleda J, Clinical clues to the causes of large pericardial effusions. Am J Med 2000; 109:95–101.

- Sagrista-Sauleda J, et al. Diagnosis and management of pericardial effusion. World J Cardiol 2011; 3:135–43.

- Saito Y, et al. The syndrome of cardiac tamponade with “small” pericardial effusion. Echocardiography 2008; 25:321–7.

- Seif D, et al. Bedside ultrasound in resuscitation and the rapid ultrasound in shock protocol. Crit Care Res Pract 2012.

- Shabetai R. Pericardial effusion: haemodynamic spectrum. Heart 2004; 90:255–156.

- Spencer K, et al. Focused cardiac ultrasound: recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2013; 26:567–81.

- Spodick D. Acute cardiac tamponade. N Engl J Med 2003; 349:684-90.

- Swami A, et al. Pulsus paradoxus in cardiac tamponade: a pathophysiologic continuum. Clin Cardiol. 2003; 26:215-217.

- Tang A, et al. Emergency department ultrasound and echocardiography. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2005;23(4):1179-94.

- Tayal V, et al. Emergency echocardiography to detect pericardial effusion in patients in PEA and near-PEA states. Resuscitation, 2003, Volume 59, Issue 3.

- Thourani V, et al. Penetrating cardiac trauma at an urban trauma center: a 22-year perspective. Am Surg, 65 (1999), pp. 811–819.

- Tsang T, et al. Echocardiographically guided pericardiocentesis: evolution and state-of the-art technique. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998;73(7):647-52.

- Tsang T, et al. Consecutive 1127 therapeutic echocardiographically guided pericardiocentesis: Clinical profile, practice patterns, and outcomes spanning 21 years. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77(5):429-36.

- Via G, et al. International evidence-based recommendations for focused cardiac ultrasound. J Am Soc Echo. 2014;27(683): e1–33.

- Weekes A, et al. Emergency Echocardiography. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2011;29(4):759-87.

- Whye D, et al. Echocardiographic diagnosis acute pericardial effusion in penetrating chest trauma Am J Emerg Med, 6 (1988), pp. 21–23.

*All videos are used with permission of Thomas G. Costantino and Ryan C. Gibbons, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple university.