Pelvic Inflammatory Disease and Tubo-ovarian Abscess

Case Study

Patient is a 25 y/o female who presents to the Emergency Center for four days of worsening pelvic pain. She states that the pain has been gradually getting worse, and now is “really bad.” She states has she has been having some nausea and intermittent subjective fevers. She notes that she has been having some abnormal vaginal discharge. When she is asked about her sexual history, she has had two sexual partners in the past year and uses condoms some of the time.

On exam, you note that she is tender in bilateral lower quadrants, right greater than left. On pelvic exam, you note purulent discharge from the cervix and severe bilateral adnexal tenderness to palpation.

The patient is concerned and asks, “What do you think the problem is Doc?”

Objectives

- Recognize the signs and symptoms of PID and TOA

- Initiate appropriate diagnostic testing

- List risk factors for PID.

- Discuss complications of PID.

- Understand the rationale for initiating treatment for patients with potential PID in uncertain cases.

- Determine which women with PID require hospitalization

Introduction

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID) is an infection of the upper reproductive tract (uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries) in females. This acute clinical syndrome frequently originates as a cervical infection with Neisseria gonorrhea and/or Chlamydia trachomatis, and becomes polymicrobial as it ascends into the uterus, fallopian tubes and ovaries. Although the incidence and hospitalization rate for PID have shown a decline in the past decade, PID remains a common serious infection in reproductive-aged women in the United States. 4.2% of women in the U.S. have been treated for PID in their lifetime.

Untreated, PID may result in an increased risk for infertility, ectopic pregnancy and Tubo-Ovarian Abscess (TOA). As such, the Emergency Medicine physician must remain vigilant and keep PID in the differential for the female with lower abdominal pain.

Initial Actions and Primary Survey

When a woman of reproductive age presents with vaginal discharge or pelvic pain, a pelvic exam and a pregnancy test should always be performed. If the patient is pregnant, other causes of pelvic pain such as ectopic pregnancy should be considered, since PID is less prevalent in pregnancy. If PID does occur in pregnancy, it is most common in the first 12 weeks of pregnancy.

Classic Presentation

Women typically present with bilateral lower abdominal pain, purulent vaginal discharge, or less frequently, with abnormal vaginal bleeding. Symptoms begin shortly after the start of the menstrual cycle, when there are fewer defenses in the cervical mucosal barrier to ascending infections. Patients may also present with fever, nausea, vomiting and general malaise, but this is variable and may range from minimally symptomatic to toxic- appearing. PID associated with gonococcal infections is typically more rapid in onset and is associated with more toxic symptoms than non-gonococcal PID.

Risk factors for PID include:

- Prior history of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs)

- multiple sexual partners

- intrauterine device (IUD) contraception use,

- adolescence (75% of PID cases occur between the ages of 15-25)

- sexual intercourse at an early age

- recent instrumentation of the uterine cavity

The most common physical exam findings are bilateral adnexal tenderness and purulent cervical discharge. Cervical motion, uterine, and lower abdominal tenderness may also be present. Unilateral adnexal tenderness or fullness may suggest the presence of a tuboovarian abscess, while right upper quadrant tenderness may suggest Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome where the infection extends to cause a perihepatitis with inflammation of the liver capsule and ‘violin string’ scar tissue formation.

Diagnostic Testing

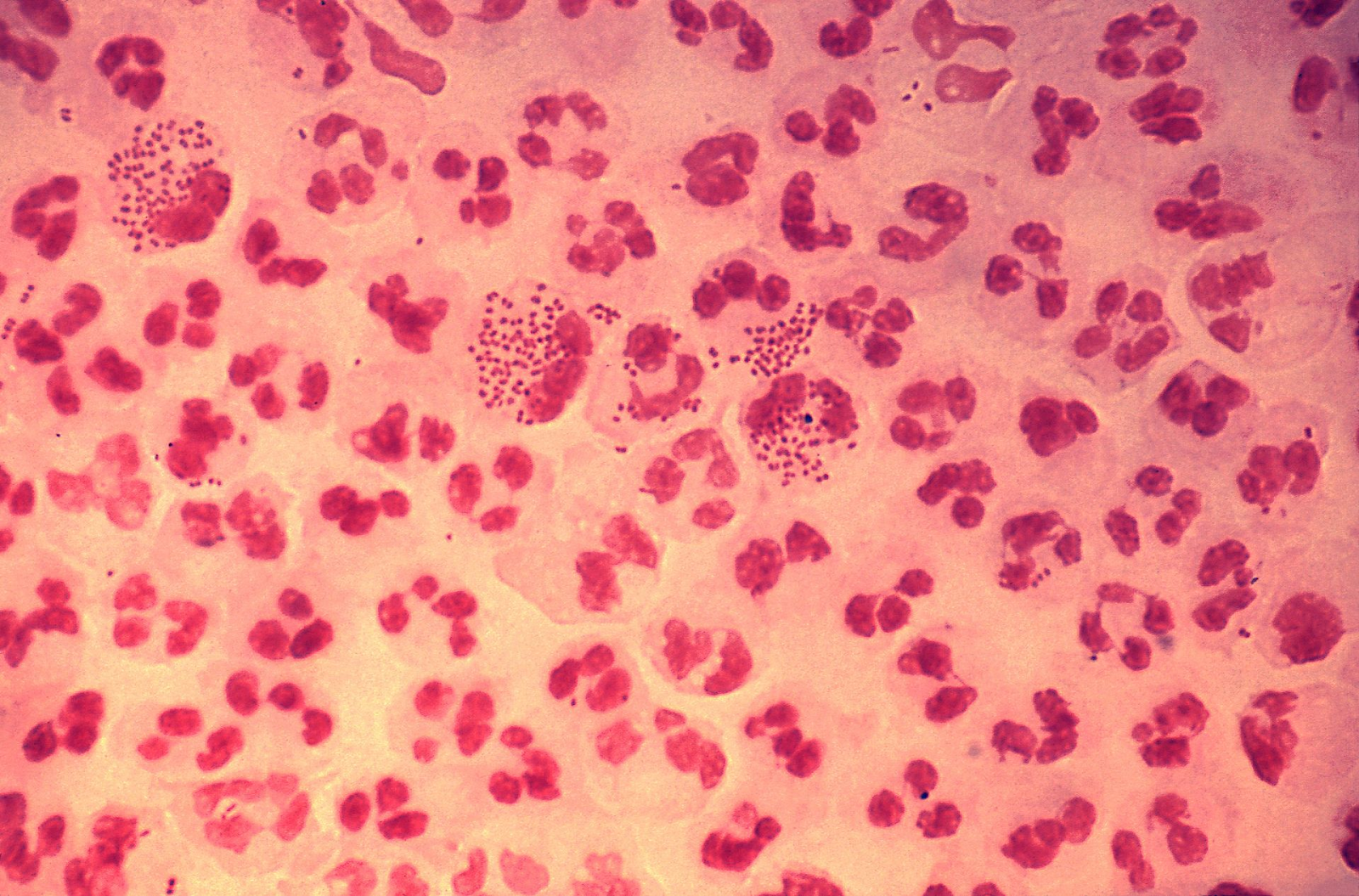

Image 1. Gram stain of urtethral swap. Presence of multiple neutrophils and the presence of intracellular and extracellular diplococci. Image courtesy of CDC via WikiImages https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neisseria_gonorrhoeae CC BY 3.0SA

Further testing should include urinalysis, CBC with differential, and liver function studies (if Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome is suspected). The most appropriate testing for Neisseria gonorrhea and Chlamydia trachomatis is by nucleic acid amplification and hybridization determination, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or DNA probes. These tests are more sensitive than cultures, can be run on cervical secretions or urine, and have a more rapid turn-around time. For the patient with severe allergies to current recommended antibiotics, culture and sensitivity on cervical secretions may need to be done. Gram stain of cervical secretions may show gram-negative intracellular diplococci in the presence of

N. Gonorrhea.

Image 2. This ultrasound image depicts a complex left ovarian mass consistent with TOA. Image reproduced with permission, ERPocketBooks.com.

Pelvic ultrasound is warranted if TOA is suspected or the diagnosis is unclear. It is particularly useful to rule out other diseases that may present with pelvic pain such as a ruptured ovarian cyst (free fluid in the pouch of Douglas) or an ovarian torsion (absence of blood flow to one ovary on pelvic ultrasound with doppler).

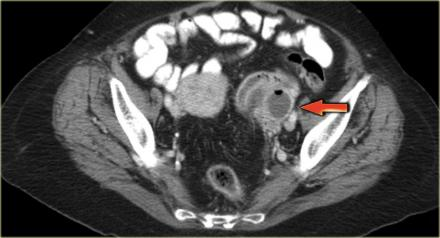

Image 3. CT scan with arrow denoting area of rim-enhancement concerning for TOA. Imagae courtesy of Radiology Assistant https://radiologyassistant.nl/abdomen/ovarian-cysts-common-lesions. Creative Commons license

CT may also demonstrate tuboovarian abscess. It is not the preferred method of diagnosis since it does not evaluate ovarian blood flow and therefore cannot rule out ovarian torsion. CT is frequently ordered in patients to evaluate for appendicitis or other suspected etiology and the scan reveals tuboovarian abscess instead. This CT reveals a complex ovarian mass, consistent with a TOA.

How do I make the diagnosis?

In a patient with a negative pregnancy test and an elevated WBC, in the setting of fever, bilateral adnexal tenderness, and a mucopurulent cervical discharge, the diagnosis of PID is certain. PCR positive for N gonorrhea or C trachomatis is pathognomonic for PID in the appropriate clinical setting, but is not usually available while formulating the treatment plan in the emergency department. Up to one-third of women with PID do not have Neisseria or Chlamydia isolated, emphasizing the polymicrobial nature of this disease.

Because of the potential complications of untreated PID and the prevalence of infection, the Center for Disease Control (CDC) has recommended initiating empiric therapy for all patients who meet minimal clinical criteria for PID. This minimum criterion includes a history of lower abdominal or pelvic pain coupled with adnexal, uterine or cervical motion tenderness on exam, in a patient at risk for STDs with no other discernible cause for the illness identified.

The complications of PID include chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, infertility, ectopic pregnancy, TOA and Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome. Women with a previous episode of PID are 12-15 % more likely to have an ectopic pregnancy.

Tubo-ovarian abscess is a walled-off abscess that originates in the infected fallopian tube and extends to involve the ovary. Women with TOA appear ill, and will often have severe unilateral adnexal tenderness and fullness on bimanual pelvic examination.

Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome is a perihepatitis that occurs in 8-10% of patients with PID. These patients appear septic as well, and often present with right upper quadrant or referred right shoulder pain. Elevated liver function studies confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment

Once the CDC minimal criteria is met, women should be treated with antibiotics that cover the multiple organisms potentially responsible for this disease , including N gonorrhea, C trachomatis, Escherichia coli, and multiple anaerobic bacteria such as Peptococcus, Peptostreptococcus and Bacteroides. The particular agent used will be determined by the toxicity of the patient.

Inpatient treatment should be started in the Emergency Department. The recommended regimen includes:

- Cefoxitin 2 grams IV q 6 hours with Doxycycline 100 mg PO or IV q 12 hours OR

- Cefotetan 2 grams IV q 12 hours with Doxycycline 100 mg PO or IV q 12 hours.

- If the patient is allergic to cephalosporins, they may be treated with Clindamycin 900 mg IV q 8 hours with Gentamycin.

- Alternatively they may be treated with ampicillian/sulbactam (Unasyn) 3 grams IV q 6 hours with Doxycycline 100 mg PO or IV q 12 hours. Doxycycline should always be given orally when possible, because it is caustic to vessels.

The recommended regimen for outpatient therapy is Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM OR Cefoxitin 2 grams IM and Probenecid 1 gram PO. Doxycycline 100 mg BID for 14 days must also be prescribed. The addition of Metronidazole 500 mg BID for 14 days should be considered in women with more severe infection or history of uterine instrumentation within the preceding 3 weeks.

Disposition

Indications for admission include suspected TOA or Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome, patients with intractable vomiting, septic patients, those with peritonitis, prepubertal children, women with an indwelling intrauterine device (IUD) and although rare, pregnant patients. The nulliparous patient should be strongly considered for admission to preserve fertility, as well as women with co-morbidities such as diabetes or AIDs, who often have a protracted course. Women with an IUD should have the IUD removed after the initiation of antibiotics.

Discharged patients should be advised to avoid sexual contact, to refer their partners for treatment, and to follow up in 72 hours, unless their symptoms worsen requiring earlier follow up. Patients should also be referred for further STD testing including HIV, hepatitis, and syphilis.

Pearls and Pitfalls

- PID is a polymicrobial infection despite being most commonly associated with Chlamydia and gonorrhea.

- Women of reproductive age who present with pelvic pain require a pregnancy test. In the pregnant patient, PID is less likely (particularly after the first 12 weeks), and other causes such as ectopic pregnancy need to be excluded.

- Consider TOA or alternative diagnosis if the patient does not improve with antibiotics.

- Patients with minimal CDC criteria should be treated for PID if no other discernible cause for their illness is identified, to reduce complications associated with untreated PID

- Pelvic ultrasound should be obtained in patients with unilateral tenderness or mass, or if the diagnosis is unclear.

- Partners of the patient should be seen and treated.

Case Study Resolution

The patient’s physical exam was concerning for PID, and the Emergency Medicine physician ordered a pelvic ultrasound to evaluate for a TOA. The ultrasound demonstrated a 4cm TOA on the right ovary. IV antibiotics were started and she was admitted to the Gynecology service. After a couple of days she improved and was transitioned to oral antibiotics and discharged home.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2015. MMWR 2015: 64(RR-3); 78-82.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update to CDC’s Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2006: Fluoroquinolones: No Longer Recommended for Treatment of Gonococcal Infection. MMWR 2007: 56(14); 332-336.

- Chomvarin C, Chantarsuk Y, Thongkrajai P, et al. An assessment and evaluation of methods for diagnosis of chlamydia and gonococcal infections. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 1997 Dec; 28 (4): 791-800.

- Dicker LW, Mosure DJ, Steece R, Stone KM. Testing for sexually transmitted diseases in U.S. public health laboratories in 2004. Sex Transm Dis 2007;34:41-6.

- Newman L, Moran JS, Workowski KA. Update on the management of gonorrhea in adults in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44:S84-S101.

- Soper DE. Pelvic inflammatory disease. Obstet Gynecol 2010; 116:419.

- http://www.cdemcurriculum.org/index.php/ssm/show_ssm/gu/toa

Author: Collette Wyte, MD, FACEP, Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine

Editor: Grace Chen MD, Tripler Army Medical Center

Last Update: November 2019