Abdominal Pain & Vomiting

Objectives

Upon finishing this module, the student will be able to:

- List the differential diagnosis of abdominal pain and emesis

- Identify the different etiologies and pathophysiology for abdominal pain

- Discuss the initial workup for key causes of abdominal pain and emesis

- Explain the mechanism behind vomiting and the difference between vomiting and infant spit ups.

- Identify the main imaging modalities useful in the workup of abdominal pain and vomiting.

Initial Actions and Primary Survey

As with any patient who presents to the emergency department, the first priority is Airway, Breathing, Circulation, and initial stabilization as needed. A focused approach focusing on the ABC’s in a child with abdominal pain and vomiting is necessary to rule out an acute cardiorespiratory process. Abdominal pain and vomiting can be the presenting symptoms of significant cardiorespiratory disease and many etiologies of abdominal pain can cause clinical deterioration and sepsis if not addressed promptly. Initially, perform a targeted history and physical followed by a detailed directed history and physical. Many patients with complaints of abdominal pain and vomiting will have self-limited conditions and will be stable on presentation. However, some require rapid diagnosis and stabilization / resuscitation.

Key points to identify are:

- Is the patient septic?

- If the patient is septic, rapid interventions such as fluid resuscitation, having the patient placed on cardiopulmonary monitoring, rapid acquisition of labs and prompt initiation of appropriate broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage can have a significant impact on patient outcomes.

- Is the patient dehydrated?

- Fluid resuscitation may be all that is needed to improve perfusion in the dehydrated child. This initially consists of giving normal saline in 20 cc/kg bolus three times before considering vasopressors.

- Is this presentation an acute abdomen?

- Rapidly identify the need for emergent or surgical intervention such as appendicitis, bowel ischemia, gonadal torsion, etc. If identified, these conditions require prompt referral to surgeons or sub specialists skilled in their specific management either within the hospital associated with the ED or via emergent referral and transfer to another center.

Abdominal pain can be divided in to three types somatic, visceral, and referred.

- Somatic pain is typically well localized and sharp in character. The pain signal travels via somatic nerves unilaterally. Somatic pain may originate from a somatically enervated organ experiencing inflammation or from inflammation in a nearby structure. The classic example of this is a later appendicitis causing a localized peritonitis in the right lower quadrant.

- Visceral pain is typically dull or achy and usually located in the epigastric, middle and lower abdomen. Visceral pain results from distension of a viscus or hollow organ. The pain signal is transmitted through autonomics that overlap with nerves from the contralateral side on their path to the CNS and results in a poorly localized pain. When asked to localize the pain a patient may use an open hand to indicate a general region as the location for visceral pain. The classic example of this is early appendicitis causing periumbilical pain from inflammation of the appendix.

- Referred pain is felt remotely from the disease site and can vary in character. This pain signal is in fact created by transmission through shared afferent nerve pathways. A classic example of this is testicular pain that is experienced as abdominal pain by the child.

These varied mechanisms for pain can be used to further understand abdominal pain and shed light on a diagnosis. For example, classically appendicitis presents as a vague pain that then localizes to the right lower quadrant. This is a transition from visceral to somatic pain as the infection /inflammation worsens and spreads from viscus to affect the abdominal wall.

Vomiting is often coupled with abdominal pain. It is a forceful coordinated expelling of gastric contents from the mouth. The control and induction of vomiting is regulated in the medulla, signals coming from a variety of areas throughout the body including chemoreceptors, nociceptors, and mechanoreceptors in the GI track, GU track, middle ear, heart as well as the brain. Serotonin plays a key role in these signals and has been targeted for antiemetic therapies. Emesis should be considered as having different probable etiologies by age groups particularly dividing infants and very young children from school aged children and adolescents.

Infants

Spitting up – This is typically smaller volume and post feeds. It is one of the most common causes of emesis in infants and is a benign condition if there is appropriate weight gain. This exists on a spectrum with gastroesophageal reflux. Most are “happy spitters.” Some infants may appear to be in pain and may benefit from acid suppression although this is by no means emergent. Some infants with gastroesophageal reflux will have paroxysmal episodes of generalized stiffening and opisthotonic posturing (Sandifer Syndrome).

Anatomic defects – Vomiting may be a presenting symptom of malrotation, volvulus, intussusception, pyloric stenosis or other anatomic problems and require the attention of a surgeon.

Necrotizing enterocolitis – Typically seen in preterm or very ill infants however can occur in healthy term neonates as well. This is less likely as they grow older.

Infection –Fever with vomiting can be the presenting symptoms in children with a serious infections (e.g. meningitis). . Fever and vomiting may also be a presenting symptoms in more commonly seen febrile illness such as otitis media or upper respiratory infection. Gastroenteritis is a common cause of fever, vomiting and diarrhea but in infants less than 6 months should be a diagnosis of exclusion. Young children with urinary tract infections (pyelonephritis) will also present with fever, vomiting and diarrhea.

Post-tussive – Triggers to cough may be potent enough that coughing results in gagging and emesis. This can be seen in any condition causing cough although it has been classically described in pertussis.

Chemical – Inborn errors of metabolism may present with emesis and have variable ages of onset although generally shortly after birth. Some can take time for metabolites to build up before symptoms appear. Additionally, many ingested substances may induce emesis and should be considered.

Older Child and Adolescent

Gastroenteritis – The most common cause of emesis in older children and adolescents. This may present with diarrhea as well. Evaluate hydration status carefully.

Obstruction – This may be secondary to incarcerated hernia, intussusception or post surgical adhesions. Suspicion for this should be dictated by H&P.

Infection – Serious infections of GI origin such as appendicitis or cholecystitis may present with emesis and require surgical referral. CNS infections may also present with emesis and clinicians should look for nuchal rigidity and other signs.

GU – Urologic processes such as nephrolithiasis particularly with obstruction as well as UTI frequently may present with emesis.

Diabetic ketoacidosis – Due to metabolic disturbances, emesis is often present.

Toxins/drugs/ingestions

OB/GYN – Pregnancy, Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

Abdominal Imaging

- Abdominal x-rays may be used to help with the diagnosis of intestinal obstruction or to show evidence of perforation such as free air within the peritoneum.

- Ultrasound is an invaluable tool in the practice of pediatric emergency medicine and even more so in patients with abdominal pain. Ultrasound with doppler may be used to rule out torsion of either an ovary or testis. It can provide a view of the kidneys and demonstrate hydronephrosis suggestive of obstruction secondary to renal stone. In younger patients, it can be used to look for intussusception and in some centers it is used in the workup of appendicitis. RUQ ultrasound is invaluable in the evaluation of patients with concern for liver and gall bladder disease. It can be used to screen for tubo-ovarian abscess or pyosalpinx. Furthermore, it can assist in determining if there is a viable intrauterine pregnancy.

- Abdominal MRI is used in some centers as first line in the diagnosis of appendicitis.

- Abdominal CT has many advantages. It is a test that can often be performed rapidly and is readily available in essentially every emergency department. It carries the risk of a high dosage radiation exposure and should be reserved for cases where other imaging will not be effective or is unable to be performed.

History and Physical Examination

Key aspects of history

History should be appropriately detailed and obtained from all available sources. An older child may provide better insight to the events leading up to their seeking care than an adult in many cases while younger children are often unreliable historians and parents must be relied upon to relate events. Health care records as well as EMS and other providers when involved can provide valuable information. History and physical exam can provide enough information to made the diagnosis in many cases, differentiating emergent from non-emergent interventions. Some causes of abdominal pain and vomiting are due to pathology outside of the GI tract (e.g. streptococcal pharyngitis).

- Duration of symptoms: acute vs chronic, constant vs. intermittent

- Pain: location, character, radiation, and severity of pain

- Exacerbating or alleviating factors for pain: oral intake vs NPO

- Presence / frequency of associated symptoms: emesis, diarrhea, cough etc. If patient has emesis or diarrhea ask whether it is bloody, green, dark or pale. Ask about changes with defecation, eating urination and position

- Oral Intake: degree of enteral nutrition and hydration; recent ingestion of food or medications , especially new foods or medications

- Past medical history and surgical history

- Family history: e.g.IBD or celiac disease

Key aspects of physical examination

- Inspection of the abdomen: This should be done first as palpation may change findings.

- Auscultation: This should also be done prior to palpation as findings may be altered. Listen in all four quadrants of the abdomen. Decreased or absent bowel sounds in a specific area may suggest pathology in this area.

- Palpation: This is the main focus of examining an abdomen. Evaluate for tenderness in specific regions of the abdomen. Initial palpation should be superficial and progress to deeper palpation. Rebound tenderness indicates a degree of peritonitis.

- Percussion: Dullness or resonance may help direct towards specific disease processes.

- Specific Signs: Specific signs such as Murphy’s, psoas, obturator and tenderness at McBurney’s point in conjunction with the remainder of H&P can have a high degree of specificity for specific disease processes.

- Determining Hydration Status: In an infant or toddler – Activity level / overall appearance, eyes (sunken or not), anterior fontanels (sunken flat or bulging when age appropriate), capillary refill time and mucous membranes. In a child or adolescent – general appearance, capillary refill time and mucous membranes

Physical Examination Clues as to the potential cause of abdominal pain:

- HEENT: Tonsil hypertrophy and erythema can indicate pharyngitis, a well known but poorly explained cause of abdominal pain and vomiting.

- Lung Exam: Auscultation of the chest may reveal a pneumonia, which can refer pain to the abdomen.

- Back Exam: Costovertebral angle tenderness may indicate pyelonephritis or GU obstruction. This physical finding is less likely to be seen in infants and young children.

- GU Exam: A pelvic exam is necessary in female patients if there is suspicion of a gynecologic process. Particular attention must be paid to evaluating cervical motion tenderness as a sign of pelvic inflammatory disease and adnexal tenderness which may help localize ovarian pathology. A GU exam is needed in male patients as well to check for hernia. Testicular pathology may present with pain referred to the abdomen.

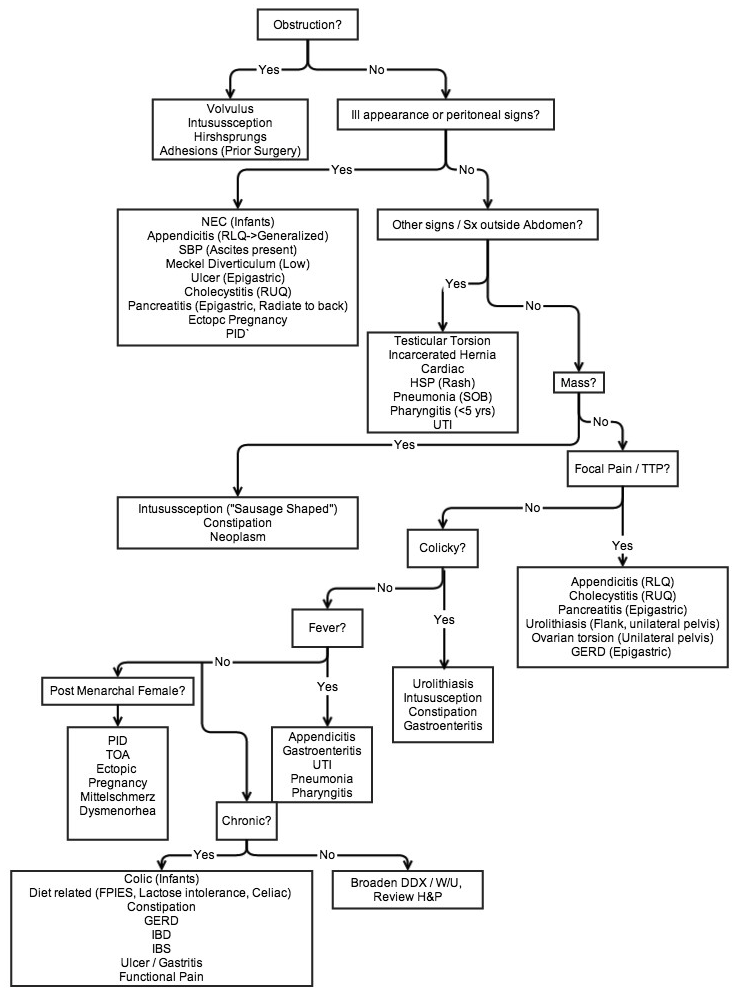

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for abdominal pain and vomiting in a pediatric patient can be broad, but here are some key diagnoses to consider in any patient with these symptoms:

- Gastrointestinal

- Gastroenteritis,constipation, appendicitis, GERD, gastritis, diverticulitis, IBD, hernia, intussusception, volvulus, post-surgical adhesions, neoplasm, sickle cell disease, abdominal migraine, celiac disease, cholecystitis, cholelithiasis hepatitis, liver abscess, pancreatitis, pyloric stenosis, colic, dehydration

- Genitourinary

- UTI,nephrolithiasis, pelvic inflammatory disease, ovarian torsion, testicular torsion, epididymitis, menstruation, Mittelschmerz, ovarian cyst, pregnancy

- Referred

- Pneumonia, asthma, pharyngitis

- Other

- Diabetic ketoacidosis, functional, irritable bowel syndrome

- Diabetic ketoacidosis, functional, irritable bowel syndrome

Conclusion

Abdominal pain in pediatric patients ranges widely in level of acuity necessitating ED practitioners to have a solid foundation in its evaluation. The need to prioritize A, B, C’s as the basis of initial assessment remains essential as with all patients seen on an urgent or emergent basis. Goals of care should include early recognition of conditions that require immediate emergent intervention or those conditions can progress to more critically ill level. Particular attention should be focused on fluid status as many children with abdominal pain may present dehydrated.

Abdominal pain in children requires a DETAILED history and physical as many conditions can be determined prior to any diagnostic testing. Be cautious with radiation in children and “image gently,” using MRI and US when appropriate and available over CT or X-ray.

Common Conditions in Children Table

Fleisher, Gary R. & Ludwig, Stephen. Textbook of pediatric Emergency Medicine: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: New York, 2010

References

- D’Agoustino J. Common abdominal emergencies in children [review]. Emerg Med Clin North Am2002;20(1):139–153.

- Fleisher, Gary R. & Ludwig, Stephen. Textbook of pediatric Emergency Medicine: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: New York, 2010

- Kim JS. Acute abdominal pain in children . Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2013 Dec;16(4):219-24. doi: 10.5223/pghn.2013.16.4.219. Epub 2013 Dec 31.

- Mason JD. The evaluation of acute abdominal pain in children. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1996 Aug;14(3):629-43.

- Moir CR. Abdominal pain in infants and children. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996 Oct;71(10):984-9, quiz 989.

- Ross, A and LeLeiko, N, Acute Abdominal Pain. Pediatrics in Review 2010; 31:135-144; doi:10.1542/pir.31-4-135

- Selbst, Steven M & Cronan, Kate. Pediatric Emergency Medicine Secrets: Hanley & Belfus inc:Philadelpia 2001

Pediatric Abdominal Pain & Vomiting

Authors: John A. Park, MD

Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center

Department of Pediatrics

Lilia Reyes, MD

Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center

Department of Emergency Medicine

Division of Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Penn State College of Medicine