Ischemic Stroke

Author: Cynthia Leung MD PhD, The Ohio State University College of Medicine.

Editor: Rahul Patwari, MD, Rush University, Chicago, Illinois.

Last Update: November 2019

Case Study

A 68-year-old female, with a history of hypertension and diabetes mellitus, presented to the ED after acute onset of speech difficulty and right-sided weakness. Her symptoms began 3 hours ago. On physical exam, the patient was found to have severe expressive aphasia, right hemiplegia, and right hemi-sensory loss.

Objectives

Upon completion of this module, the student will be able to:

- Recognize signs and symptoms of stroke

- Identify clinical features suggestive of common stroke mimics

- Describe the initial management of acute stroke

- Discuss the treatment options for acute ischemic stroke

Introduction

Stroke is the fifth leading cause of death and the leading cause of disability in the US with estimated direct and indirect costs of roughly 70 billion dollars per year. Based on current estimates, the prevalence of stroke is expected to increase by twenty percent by the year 2030. Advancements in the diagnosis and treatment of stroke must continue to compensate for the increasing stroke burden on our society.

Stroke is characterized by the acute onset of neurologic deficit caused by disruption of cerebral blood flow to a localized region of the brain. The reversibility and extent of symptoms in stroke is critically dependent on the duration of this disruption. Therefore, early recognition and treatment is the key to reducing morbidity and mortality associated with stroke. As the first physician to see the patient with acute stroke, the actions of the Emergency Physician can have a profound impact on the outcome of stroke patients.

Acute stroke most commonly results from occlusion of an intracranial artery by thrombosis within the artery, thromboembolism from an extracranial source, or hemorrhage. Eighty seven percent of strokes are ischemic in etiology, with the remainder caused by intracerebral or subarachnoid hemorrhage. This module will focus exclusively on the evaluation and treatment of acute ischemic stroke. The evaluation and treatment of hemorrhagic stroke can be found in the intracranial hemorrhage module.

Patients with stroke may present with a variety of neurologic symptoms including changes in vision, changes in speech, focal numbness or weakness, disequilibrium or alteration in level of consciousness. There are many alternate diagnoses that can mimic the symptoms of stroke.

The differential diagnosis includes:

- Structural brain lesion (tumor, AVM, aneurysm, hemorrhage)

- Infection (cerebral abscess, septic emboli)

- Seizure Disorder and post-seizure neurologic deficit (Todd’s paralysis)

- Peripheral Neuropathy (Bell’s palsy)

- Complicated Migraine

- Toxic-metabolic disorders (Hypoglycemia and Hyponatremia)

- Conversion Disorder

Initial Actions and Primary Survey

The initial actions in the evaluation of a patient with suspected stroke begin with emergent stabilization of the patient. As with any emergent patient, the primary survey includes assessment of the patient’s airway, breathing and circulation. Hypoxemia and hypotension due to stroke or co-morbid conditions may worsen stroke symptoms and lead to death. Therefore, treatment of any critical conditions found on primary survey must be initiated prior to continuing the evaluation. Next, a focused H&P is performed to assess level of neurologic dysfunction, exclude alternate diagnoses, and determine the patient’s eligibility for therapy.

Presentation

The initial diagnosis of acute stroke is based on clinical findings. Part of the challenge in making the diagnosis is that there is no “textbook” presentation of stroke. The signs and symptoms of stroke are highly variable and depend not only on the particular blood vessel occluded, but also the extent of occlusion and amount of circulation provided by collateral vessels. Presentations may vary from multiple profound neurologic deficits in a large vessel occlusion to very subtle isolated deficits when smaller vessels are occluded.

The single most important component of the history is the exact time of onset of symptoms. This is defined as the time when the patient was last known to be symptom-free, commonly referred to as the “last known well”. In cases where the patient’s last known well time is unclear, focused questions should be deployed to help narrow down the time window as much as possible. For example, if the patient awakens from sleep with symptoms, questioning the patient about waking in the middle of the night to walk to the restroom or kitchen may help to determine a more accurate last known well time. In patients who were awake during symptom onset, asking about specific activities such as phone calls or television shows may help to further focus the timeframe of onset. Friends and family should also be asked to provide collateral information when possible.

The remainder of the history should focus on factors which may help differentiate a stroke mimic from a true stroke. The HPI should include a detailed history of the onset, time course and pattern of symptoms to help distinguish between stroke and alternate diagnoses. Symptoms which achieve maximal intensity within seconds to minutes of onset and simultaneously affect multiple different systems at once are typical of stroke. In contrast, symptoms which progress slowly over time or progress from one area of the body to another are more suggestive of stroke mimic. The past medical history should include assessment of stroke risk factors as well as risk factors for stroke mimics. Stroke risk factors include hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, tobacco abuse, advanced age, atrial fibrillation or prosthetic heart valve, and prior stroke. In patients receiving thrombolytic therapy, the most common stroke mimics include complicated migraine, seizure and conversion disorder. A past medical history which includes any of these disorders should heighten suspicion of these alternate diagnoses.

Once the primary survey is complete, a thorough neurologic exam should be performed. This should include assessment of level of consciousness, cranial nerves, strength, sensation, cerebellar function and gait.

Common Stroke Syndromes

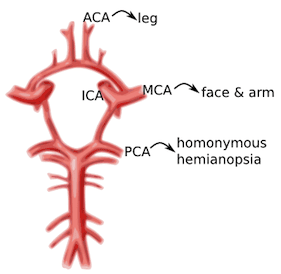

Signs and symptoms of stroke should follow a vascular distribution of the brain. Knowledge of the functional areas supplied by each of the major intracranial blood vessels helps to predict signs and symptoms associated with occlusion of that particular vessel.

Image 1. Circle of Willis and the primary cerebral vessels. Labels added. Contect accessed from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/imagepages/18009.htm

Anterior Cerebral Artery (ACA): unilateral weakness and/or sensory loss of contralateral lower extremity greater than upper extremity

Middle Cerebral Artery (MCA): unilateral weakness and/or sensory loss of contralateral face and upper extremity greater than lower extremity with either aphasia (if dominant hemisphere) or neglect (if non-dominant hemisphere)

Posterior Cerebral Artery (PCA): unilateral visual field deficit in both eyes (homonymous hemianopsia).

Vertebrobasilar syndromes have multiple deficits which typically include contralateral weakness and/or sensory loss in combination with ipsilateral cranial nerve palsies. Suspicion for posterior circulation stroke is heightened if the patient exhibits one of these signs or symptoms beginning with “D”: diplopia, dysarthria, dysphagia, droopy face, dysequilibrium, dysmetria, and decreased level of consciousness. Nausea and vomiting are also frequently associated with brainstem stroke.

Lacunar infarcts are small strokes (measuring less than 1.5 cm) caused by occlusion of one of the deep perforating arteries which supplies the subcortical structures and brainstem. Lacunar infarcts can produce a large variety of clinical deficits depending on their location within the brainstem and have been characterized by more than 70 different clinical syndromes. However, the vast majority of lacunar strokes are described by the 5 most common lacunar syndromes: pure motor hemiparesis, sensorimotor stroke, ataxic hemiparesis, pure sensory stroke, and dysarthria-clumsy hand syndrome.

Diagnostic Testing

Rapid evaluation of patients with suspected stroke is critical because there is a very narrow time window in which stroke patients are eligible for treatment. A panel of experts convened by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) has established several critical events in the identification, evaluation, and treatment of stroke patients in the ED. The most important of these time goals include a door to head CT time less than 25 minutes and a door to drug administration time of less than 60 minutes.

The diagnosis of stroke is based primarily on clinical presentation. The NIH Stroke Scale (NIHSS) provides a standardized clinical assessment which is generalizable from one physician to another and allows monitoring of the patient’s neurologic deficits over time. The NIHSS can serve as a measure of stroke severity and has been shown to be a predictor of both short and long term outcome of stroke patients. Many Emergency physicians find it convenient to keep an App on their phone to aid in rapidly calculating the NIHSS. There are also a variety of on-line NIHSS calculators available, such as the one found on MDcalc.com

The remainder of the diagnostic workup is focused on excluding alternative diagnoses, assessing for comorbid conditions and determining eligibility for therapy. The diagnostic workup includes:

Brain Imaging

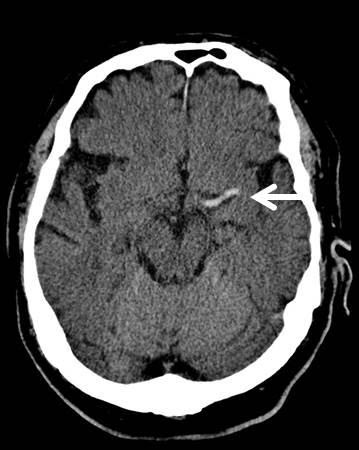

Head CT without contrast should be performed on all patients to exclude intracranial hemorrhage. Unenhanced head CT is often able to identify other structural brain lesions and may detect early signs of stroke. Because radiologic changes associated with stroke are usually not visible on CT for several hours, the most common CT finding in acute ischemic stroke is normal brain. However, multiple subtle findings associated with acute ischemic stroke may be present in the first 3 hours after symptom onset. The earliest finding that may be seen on CT is hyperdensity representing acute thrombus or embolus in a major intracranial vessel. This is most frequently seen in the MCA (“hyperdense MCA sign”, see Image 2) and basilar arteries (“hyperdense basilar artery sign”). Subsequent findings include subtle hypo-attentuation causing obscuration of the nuclei in the basal ganglia and loss of gray/white differentiation in the cortex. Frank hypodensity on CT is indicative of completed stroke and may be a contraindication to thrombolytic therapy.

Image 2. MCA sign on CT head. Case courtesy of A.Prof Frank Gaillard, <a href="https://radiopaedia.org/">Radiopaedia.org</a>. From the case <a href="https://radiopaedia.org/cases/7150">rID: 7150</a>

At specialized stroke centers, alternative testing such as diffusion weighted MRI (DWI) or CT angiography/CT perfusion studies may also be performed as these modalities are more sensitive for detecting early or evolving infarct and may help determine the most appropriate therapy.

Serum Glucose

Hypoglycemia may cause alteration in level of consciousness and any variety of neurologic symptoms. Point of care blood glucose level must be performed to exclude hypoglycemia prior to initiation of thrombolytic therapy.

EKG

EKG should be performed to exclude contemporaneous acute MI or atrial fibrillation as these conditions are frequently associated with thromboembolic stroke.

Additional laboratory studies

CBC, chemistries, PT/INR, aPTT, and cardiac markers are recommended to assess for serious comorbid conditions and aid in selection of therapy. Treatment should not be delayed for results of these additional studies unless a bleeding disorder is suspected.

Treatment

The main goal of therapy in acute ischemic stroke is to remove occlusion from the involved vessel and restore blood flow to the affected area of the brain. The AHA/ASA currently recommends two forms of treatment for eligible patients with acute ischemic stroke: intravenous thrombolytic agents and mechanical thrombectomy.

Intravenous Thrombolytic Therapy

Intravenous recombinant Tissue Plasminogen Activator (rtPA) is a fibrinolytic agent that catalyzes the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin, the major enzyme responsible for clot breakdown. Treatment with IV rtPA has been shown to increase the percentage of patients with good functional outcome at 3 months and 1 year after stroke onset.

rtPA has been FDA approved for use in adult patients with symptoms attributable to ischemic stroke up to 3hrs after symptom onset. In addition, the American Heart Association has recommended rtPA for use up to 4.5 hours after symptom onset in a select subgroup of patients. Good functional outcomes are most likely to be achieved if rtPA is administered within 90 minutes of symptom onset. The likelihood of a good outcome decreases with increasing time from onset of symptoms. Therefore, every effort should be made to ensure that there are no delays in administration of thrombolytic therapy to eligible patients.

The major complication of rtPA administration in stroke is symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage. Careful selection of patients with an appropriate risk/benefit ratio is imperative to reduce the risk of symptomatic ICH. Exclusion criteria most commonly reflect factors that may increase likelihood of ICH including uncontrolled severe hypertension, coagulopathies, recent intracranial or spinal surgery, recent head trauma or stroke and history of prior ICH. The full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria for intravenous rtPA therapy can be found in the most recent version of the AHA Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke (see references below).

In addition, strict adherence to the NINDS recommended protocol for administration of rtPA is critical to successful treatment in stroke patients. This protocol specifies important aspects of care during and after administration of rtPA. Admission to an ICU or stroke unit, frequent reassessment of the patient’s neurologic status and careful blood pressure monitoring are all vital in the first 24 hours after administration of rtPA. Most importantly, any patient who develops acute severe headache, acute severe hypertension, intractable nausea and vomiting, altered mental status or other evidence of neurologic deterioration during or after rtPA administration should have emergent noncontrast head CT to evaluate for ICH. In addition, rtPA infusion should be discontinued immediately if it has not already been completed.

Mechanical Thrombectomy

Mechanical thrombectomy is recommended for adult patients with ischemic stroke caused by occlusion of the internal carotid or proximal middle cerebral (M1) arteries and an NIHSS greater than 6, presenting within 6 hours of symptom onset. Thrombectomy is also recommended for a select group of patients presenting up to 16 hours after symptom onset if they have demonstrated perfusion mismatch on MRI or CTP and meet additional eligibility requirements. This recommendation was based on pooled analysis of 5 studies which demonstrated lower degree of disability at 3 months in patients undergoing mechanical thrombectomy compared to those undergoing thrombolytic therapy alone. This effect was most pronounced when the time from symptom onset to thrombectomy was under 2 hours, but persisted up to 7 hours after symptom onset.

Supportive Care

Unfortunately, only a small percentage of stroke patients present to the ED within the time limit to receive specialized therapy. In stroke patients not receiving rtPA or mechanical thrombectomy, the goal of care is to prevent or treat acute complications by providing supportive care. This includes ventilatory support and oxygenation if needed, prevention of hyperthermia, cardiac monitoring, and control of blood pressure and blood glucose.

Goals for Blood Pressure Control

In patients receiving intravenous rtPA, the rate of symptomatic ICH is directly related to increasing blood pressure. Therefore, strict guidelines for blood pressure control must be enforced in these patients to prevent ICH. Blood pressure should be maintained below 180/105 mm Hg in the first 24 hours after receiving thrombolytic therapy.

In contrast, the ideal blood pressure range for acute stroke patients not receiving thrombolytic therapy has not yet been determined. The current recommendations stress the importance of an individualized approach to blood pressure control with avoidance of hypotension or large fluctuations in blood pressure. For patients who do not have other medical conditions requiring aggressive blood pressure control, antihypertensive treatment should not be initiated unless blood pressure exceeds 220/120 mm Hg.

Antiplatelet Therapy

Administration of Aspirin within 48 hours after stroke has been shown to improve outcomes by reducing the rate of early recurrent stroke. In stroke patients not receiving rtPA, oral administration of aspirin within 24 – 48 hours of stroke onset is recommended. The safety of antiplatelet agents in combination with thrombolytic therapy has not been established. Therefore, aspirin should not be administered for at least 24 hours after administration of rtPA

Pearls and Pitfalls

- Use creative questioning to establish time of onset.

- Consider common conditions which may mimic the symptoms of stroke including seizure, complicated migraine, hypoglycemia, and conversion disorder. All adult patients presenting with neurologic deficit attributable to ischemic stroke within 3 hours of symptom onset should be considered for thrombolytic therapy.

- Minimum workup prior to thrombolytic therapy includes focused H&P, CT Head to exclude intracranial hemorrhage and point of care blood glucose level to exclude hypoglycemia.

- Time is brain! Do not delay administration of thrombolytic therapy to eligible patients.

- Adult patients presenting with acute ischemic stroke due to large vessel occlusion within 16 hours of symptom onset should be considered for mechanical thrombectomy.

- Patients that do not receive thrombolytic therapy should receive aspirin within 24 hours of symptom onset.

Case Study Resolution

The patient’s initial NIHSS was 11. Noncontrast CT of the head did not show any evidence of ICH. CT angiography revealed left M1 occlusion. The patient underwent mechanical thrombectomy with marked improvement in symptoms. Repeat NIHSS was 3. The patient was transferred to the neurologic critical care unit for further monitoring.

References

Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke. Powers WJ, et al. Stroke 2018 Mar;49(3): e46-e99. PMID:29367334

Heart disease and StrokeStatistics—2018 Update: a report from the American Heart Association. Benjamin ES, et al. Circulation. 2018 Mar 1;137(12):e67-e493. PMID:29386200

Safety of thrombolysis in stroke mimics: results from a multicenter cohort study. Zinkstok SM, et al. Stroke. 2013 Apr;44(4):1080-4. PMID:23444310

Time to Treatment with Endovascular Thrombectomy and Outcomes from Ischemic Stroke: A Meta-analysis. Saver JL, et al. JAMA 2016; 316(12):1279-1288. PMID:

Time to treatment with intravenous alteplase and outcome in stroke: an updated pooled analysis of ECASS, ATLANTIS, NINDS, and EPITHET trials. Lees KR, et al. Lancet. 2010 May 15;375(9727):1695-1703. PMID:20472172