Testicular Torsion

Author: Allison Tadros, MD. West Virginia University.

Editor: G. Carolyn Clayton, MD. Rush University.

Updated: November 2019

Case Study

23 year old male with no past medical history presents with sudden onset of left groin and scrotal pain. Patient reports that his symptoms started approx 45 mins prior while playing basketball. The pain has been constant without relieving factors. Pt states that he has tried rest and ice without improvement. Denies penile discharge, dysuria or abdominal pain but complains of persistent nausea and two episodes of vomiting. On exam HR 103, RR 20, BP 145/98, SpO2 98% on RA. Abdominal exam is significant for mild left lower abdominal tenderness. Examination of the left scrotum demonstrates mild swelling and erythema with an absent cremasteric reflex. Palpation of the testicle is difficult secondary to pain , however the left testicle is slightly more full than the right and slightly higher. The remainder of the exam is unremarkable.

Objectives

- Recognize the typical presenting signs and symptoms of testicular torsion

- Describe both initial and definitive management of testicular torsion

- Explain why torsion is an emergent condition and discuss the timeline for salvage of the testicle

Introduction

Testicular torsion is a result of the twisting of the testis and spermatic cord within the scrotum, with resultant occlusion of venous return and edema. If the torsion persists, it can lead to arterial occlusion and ischemia. Ischemia eventually leads to infarction and can result in decreased fertility due to loss of the testicle. Treatment of testicular torsion is a true urologic emergency, so diagnosis and management and should not be delayed.

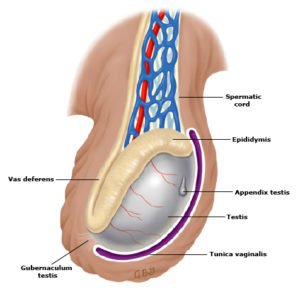

Figure 1. Anatomy of the testicle. http://sjrhem.ca/rcp-the-acute-scrotum/

Normally the testicle is anchored within the scrotum by the tunica vaginalis, which surrounds the testicle and attaches posteriorly to the scrotal wall and epididymis. The tunica vaginalis consists of a visceral and parietal layer with an interposed potential space. This potential space allows the testicle to rotate about the spermatic cord within the tunica vaginalis if a firm posterior scrotal attachment is lacking. When the tunica vaginalis attaches higher up on the spermatic cord, the testicle can move and twist within the scrotum (“bell-clapper” deformity). This places the testicle and spermatic cord at risk for torsion.

The appendix testes are embryonic remnants that have no known function and are located on the upper pole of the testicle. The appendix testes are prone to torsion as well, and present with symptoms that can mimic torsion of the testicle.

Initial Actions and Primary Survey

- Perform a focused history and physical examination

- Pain control

- Order or perform an ultrasound with Doppler flow to assess for the presence or absence of vascular flow if the diagnosis is unclear.

- Consult urology early if torsion is suspected.

Differential Diagnosis

- Testicular torsion

- Torsion of the appendix testis

- Epididymitis

- Orchitis

- Renal colic

- Varicocele

- Appendicitis

- Hernia

- Hydrocele

- Testicular trauma

Classic Presentation

Although it can occur at any age, testicular torsion is most common in the first year of life (including the prenatal period) and at puberty. Patients should be asked about the time of onset of their symptoms and if there are any associated urinary symptoms, fever, or trauma. Patients often describe fairly sudden, severe unilateral testicular pain, sometimes radiating into the abdomen. They may have associated nausea and vomiting. The left testicle is more frequently affected. Torsion may result from direct trauma to the testicle, and the diagnosis may be delayed if the patient’s pain is attributed solely to the injury itself. A small number of patients will describe intermittent testicular pain that resolves spontaneously. This history is highly suspicious for torsion-detorsion and should be referred promptly to an urologist to avoid acute torsion and testicular ischemia and loss.

On physical examination, the patient is often in significant distress, and may have trouble walking due to severe pain. The physical examination may be very difficult to perform since the patient frequently experiences a tremendous amount of discomfort. Always examine the unaffected testicle first, in both the supine and standing position. The affected testicle is usually exquisitely tender and swollen. It may sit higher within the scrotum than the unaffected testicle, and may have a transverse lie. Prehn’s sign describes the relief of pain with elevation of the testicle. Though it was once touted as a method to distinguish epididymitis from torsion, since the pain associated with torsion is usually not relieved with elevation of the testicle, Prehn’s sign is unreliable in differentiating these two entities. Several studies have found loss of the cremasteric reflex to be the most accurate sign of testicular torsion. This reflex is elicited by stroking the ipsilateral thigh which leads to reflex elevation of the ipsilateral testicle by greater than 0.5cm. The inguinal area should also be examined for hernias.

Diagnostic Testing

Laboratory analysis of blood and urine is usually not helpful. If infectious epididymitis or orchitis is suspected, then it is reasonable to perform a urinalysis and testing for gonorrhea and chlamydia. Caution should be exercised, however, since as many as 30% of patients with torsion will have white blood cells present on the urinalysis. Regardless, the management of suspected torsion should not be delayed for any lab results.

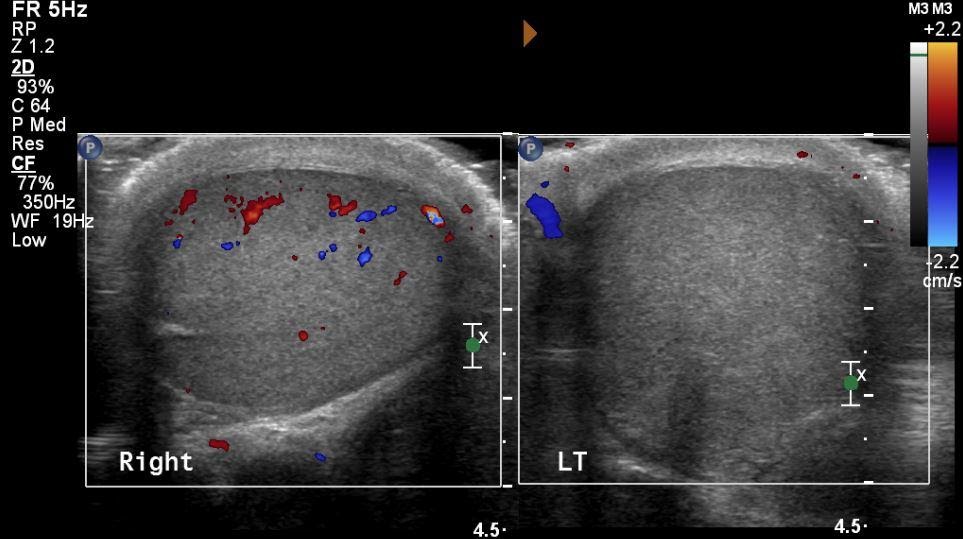

Ultrasound is the test of choice in the emergency department to diagnose torsion when the clinical diagnosis is not clear. Comparison of the painful testis to the asymptomatic one is key: the painful testicle is usually enlarged and hypoechoic, with decreased blood flow, compared to the asymptomatic side. Twisting of the spermatic cord may be also visible on ultrasound. In contrast, epididymitis is usually associated with increased blood flow to the testicle and the epididymis, as part of the body’s inflammatory response.

Side-by-side US with Doppler imaging. Note the decreased Doppler flow of the left testicle indicating a torsion of the left testicle. Original image by Dr. Allison Tadros (photo courtesy of WVU Department of Radiology). Used under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0.

How do I make the diagnosis?

Testicular torsion is primarily a clinical diagnosis. If a patient has the classic symptoms of sudden onset of pain, diffuse swelling and testicular tenderness, and loss of cremasteric reflex, a presumptive diagnosis can be made and no further testing is necessary. However, if the presentation is less classic, a urinalysis and ultrasound with Doppler flow should be performed. Table 1 summarizes some of the differences between testicular torsion and two other common causes of the acute scrotum: torsion of a testicular appendage and epididymitis.

Table. 1 Distinguishing features of testicular torsion, torsion of a testicular appendage, and epididymitis

While ultrasound is the most useful diagnostic modality to diagnose torsion, definitive diagnosis is only made at surgery. Do not delay calling a urologist if you suspect torsion.

Treatment

As with any emergency department patient, start with a primary assessment: airway, breathing, and circulation. Anyone with a suspected torsion should have an IV placed. Treat pain and nausea with IV medications, and keep the patient NPO in preparation for admission to the OR.

If you anticipate any delay in getting the patient to the OR, you may attempt a manual detorsion to restore blood flow to the affected testicle. Place the patient in a supine position and stand facing towards the patient’s head. To manually detorse the testicle, grasp it gently and rotate it away from midline, as if you are opening a book. Most torsions involve one or more complete (360°) rotations, so you may need to make two or three complete rotations of the testicle. When the maneuver is successful, patients report dramatic pain relief within minutes. The lie of the testicle may normalize and blood flow should be restored on ultrasound. While most torsions occur toward the patient’s midline, a minority will twist in the opposite direction. Therefore, if it is difficult to untwist in one direction, try untwisting in the opposite direction.

Definitive treatment of testicular torsion is surgical. The testicle must be completely untwisted as soon as possible to restore blood flow. While there is no absolute cut-off to ensure viability, some studies have indicated that the best outcomes are achieved if the testicle is detorsed within 6 hours. If, on surgical examination, testicular tissue is obviously necrotic, it may be removed. However, salvage is obviously desired and usually attempted. In addition, bilateral orchiopexy is usually performed to prevent future torsion and preserve fertility.

Pearls and Pitfalls

Call a urologist immediately before the ultrasound is obtained if you suspect the diagnosis. Testicular nonviability can occur in a little as 6 hours after onset or torsion.

Consider torsion in any patient with testicular trauma who still has pain 1-2 hours after an injury.

Ultrasound is most useful if it is performed bilaterally, to compare the asymptomatic testicle to the painful one.

Testicular torsion is primarily a clinical diagnosis and ultrasound should only be ordered if the diagnosis is unclear. Do not delay management of the patient if ultrasound is not immediately available.

Case Study Resolution

You attempt a manual detorsion of the testicle with some improvement in pain. However approximately 5 minutes later the patient's symptoms return. An ultrasound of the scrotum and tesiticles is performed. The ultrasound demonstrates a decreased blood flow to the left testicle and twisting of the spermatic cord. Urology is emergently consulted and the patient is taken to the OR for surgical exploration. The testicle is successfully detorsed and affixed to the scrotum.

Additional Resources

Approach to the Acute Scrotum http://sjrhem.ca/rcp-the-acute-scrotum/

References

- Lewis AG, Bukowski TP, Jarvis PD, et al. Evaluation of acute scrotum in the emergency department. J Pediatr Surg 1995; 30:277.

- Manohar CS, Gupta A, Keshavamurthy R, Shivalingaiah M, Sharanbasappa BR, Singh VK. Evaluation of Testicular Workup for Ischemia and Suspected Torsion score in patients presenting with acute scrotum. Urol Ann. 2018 Jan-Mar;10(1):20-23.

- Wright S, Hoffmann BE Emergency ultrasound of acute scrotal pain. Eur J Emerg Med. 2015 Feb;22(1):2-9.